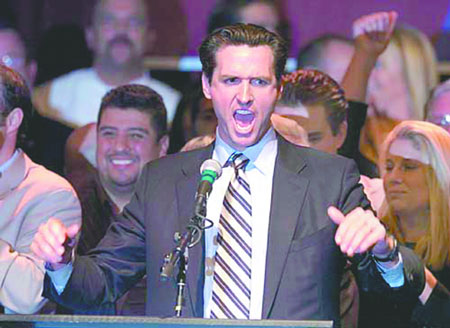

San Francisco’s bold new mayor, Gavin Newsom.

On February 24,the official black Lincoln Town Car assigned to Gavin Newsom, San Francisco’s recently elected mayor, was parked outside a side door of the basement of City Hall. The car usually sits in a prominent spot at the bottom of the wide granite staircase descending grandly from the ornate entrance of the building, but on this cloudy cold Tuesday, a protest about a proposed housing development occupied the parking space.

A few moments later, preceded by his press secretary, followed by a police officer in his guard detail, a very concerned looking Gavin Newsom hurried, eyes downcast, from the basement door. Normally very upbeat and smiling, the 36-year-old Newsom looked around, gave a half-hearted wave to a couple of bystanders, and ducked into the back door of the limousine.

Newsom was on his way to tape the first of two interviews of the day, this one with Ted Koppel of “Nightline.” The second interview would be a live spot with Larry King.

For the first few days after Newsom’s historic decision to begin marrying same-sex couples in San Francisco, a few scattered municipalities started showing support for his historic move. In the tiny New Mexico town of Bernalillo, the county clerk, a Republican, issued about 60 marriage licenses before she was shut down by the state attorney general.

“It’s going to be across the country, and so we wanted to be ahead of the curve,” said the clerk, Victoria Dunlap.

In the same week, the mayors of Chicago, Minneapolis, and Salt Lake City talked about their support for gay marriage.

But none of them have acted. So on Koppel’s program Newsom was alone, standing in a studio at a local network affiliate, defending his decision to begin performing the first same-sex marriages in America, against a barrage of questions––on the day that the president of the United States stated his support for a constitutional amendment to permanently ban gay marriage.

“One man’s move sets the stage for a constitutional battle,” Koppel intoned in his introduction.

And Newsom has been increasingly isolated politically. Politicians, even gay politicians, both in California and across the country, have moved to distance themselves from this straight, white political novice who has said in dozens of interviews that he decided to allow the marriages because “it’s the right thing to do.”

California’s Barbara Boxer, a U.S. Senator up for re-election, has said that marriage is only between a man and a woman. Her senior colleague, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, also condemned Newsom’s actions.

“If you don’t like the law, the way our system works, you try to change it,” Feinstein said, suggesting that Newsom was defying the law.

Feinstein endorsed him for mayor, but her reaction to his decision on same-sex marriages did not surprise many of the activists involved in gay rights issues in California. In the early 1980s, when she was mayor of San Francisco, Feinstein vetoed the city’s first domestic partner legislation, after coming under heavy pressure from the city’s Catholic archbishop. Even now, Feinstein does not support the Permanent Partners Immigration Act (PPIA), federal legislation that would allow the undocumented partners of gays and lesbians to legally reside in the United States.

Even one of San Francisco’s Democratic representative in the House, Nancy Pelosi, the minority leader, does not support Newsom’s marriage initiative.

“She’s proud to represent a city that will not tolerate discrimination of any kind,” said spokesperson Dan Bernal.

Lesbian activist Carole Migden, a candidate for the state Senate, takes a broader view, refusing to criticize other Democratic Party leaders.

“Let’s give people some room,” she said, a few days after her own marriage to her partner of 20 years, conducted by Mayor Newsom himself. “Having lived as an outlaw, I don’t want to quibble…. It’s good times.”

But the most surprising challenge came from a gay member of Congress, Massachusetts’ Barney Frank. Standing on a downtown San Francisco street corner, in front of a Democratic Party fundraiser a week after the marriages began, he blasted Newsom. He called Newsom’s official civil disobedience an “illegitimate act.” Did it serve to advance the discussion about gay marriage? “No,” Frank said. “I’ve been on every television station in the United States… so the argument that you need to do this in order to get the discussion going isn’t right… The discussion’s going.”

Frank said he has a strategic difference with Newsom. Same-sex marriages are due to start in Massachusetts in May and opponents, Frank says, are threatening civil disobedience to stop them.

“In Massachusetts it’s very important for us to say, ‘No, no, we’re going to follow the law.’”

Frank said that San Francisco’s gay nuptials are not real.

“Nobody thinks what they’re seeing here is marriage,” he said, adding, “We’re going to have actual marriage in Massachusetts.”

Some Newsom supporters offered insight into why the San Francisco mayor is not winning more accolades.

“I’m not surprised,” said state Senator Sheila Kuehl, who was the first openly gay legislator elected in California. “In some ways it is because this issue has overtaken the whole country and its political structure over a very, very short time. Everyone thought they were in a very good supportive position to the community by supporting civil unions. They felt that it was a sanctioned view from the community. The community was not pressing for gay marriage. They thought they were doing the right thing according to the [Human Rights Campaign]. And suddenly this issue took on 6,000 human faces.”

Even out gay activist San Francisco Assemblymember Mark Leno, at a pro-marriage rally in the state capital, Sacramento, said that previously he was content to settle for California’s domestic partnership statutes, which confer most of the same rights under state law as does marriage

“What’s in a word?” Leno asked rhetorically.

Now Leno himself has performed more than 150 ceremonies and says the difference has become personal for him. It’s the level of commitment, he says since couples are pledging to be “spouses for life.”

“When I first heard about it I was skeptical,” said Matt Foreman, head of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. “But the minute those pictures came out, waiting in line, going in, and getting married, it put a human face on this issue. Marriage is not about a packet of benefits and rights; it’s about expressing love and commitment to another human being.”

Pres. George W. Bush’s declaration of support for a constitutional amendment this week dramatically shifted the battleground from San Francisco––and Boston––to Washington.

Activists, like Geoff Kors, who heads California’s LGBT lobby, Equality California, thinks that’s just fine.

“The shift has gone from whether San Francisco should issue marriage licenses, to the constitutional amendment,” he said. “[Bush] has helped those politicians who are generally supportive of LGBT issues, but haven’t voted our way all the time. And it has galvanized people to not amend the Constitution. There will a strong backlash against the president.”

At the moment, national polls show that Newsom’s strongest support is centered around San Francisco, from where it radiates weakly. A local poll shows that half of the city’s voters strongly support what Newsom has done. Californians, generally more conservative outside of the urban centers of Los Angeles and San Francisco, are more divided on Newsom. On a constitutional amendment, California and the rest of the nation are about evenly split, according to recent L.A. Times and Washington Post polls.

Democratic presidential candidates Sens. John Kerry and John Edwards are cognizant of these poll numbers. Both favor civil unions, and oppose a federal constitutional amendment. Front-runner Kerry hasn’t stated a position on the proposed amendment to the Massachusetts constitution saying that he hasn’t seen the language which remains to be hammered out in the next session of a state constitutional convention on March 11.

“Senator Kerry is against gay marriage, he has made that clear,” Kerry spokesperson Stephanie Cutter told Gay City News. “But he does not want to make this an issue… I am not going to play the game of responding to hypotheticals about a state constitutional amendment.”

Most LGBT activists want to give Kerry some room to move, on the theory that he’ll be more supportive than Bush. But NGLTF’s Foreman is sharply critical of politicians without the excuse of a national election.

“I don’t think most elected officials understand how their actions today are going to be viewed in even ten years,” he said. “People who took a stand for what’s right are going to be honored and applauded. Those who didn’t have guts to take a stand are going to be vilified and pitied.”

Some have stepped forward. Leno has introduced a gay marriage bill in the California Assembly, and now has 20 co-sponsors for a bill that Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger is sure to veto if it passes the legislature.

Meanwhile, court challenges continue. On Febrary 24, after they were turned down by two trial courts, same-sex marriage foes asked California’s Supreme Court to stop the gay weddings in San Francisco.

Schwarzenegger has demanded that Attorney General Bill Lockyer, a Democrat, step in to stop the marriages. Lockyer initially dismissed the demand as political rhetoric, but has since bowed to Republican pressure and asked for an immediate hearing in the state Supreme Court.

Foreman says that politically, the debate is at a tipping point right now.

“It’s a fight to the death,” he said. “Either they are going to succeed in setting us back generations, or we are going to move ahead more quickly than we ever dreamed possible. It won’t be in between.”

California’s Kuehl said that for elected officials the debate would have to move from a matter of popularity to a matter of conscience. Most of her colleagues backing Leno’s marriage bill, according to Kuehl, feel that this is a historic time in California.

“In time they will be able to say to their grandchildren, ‘I was on the right side of this issue,’” she said.