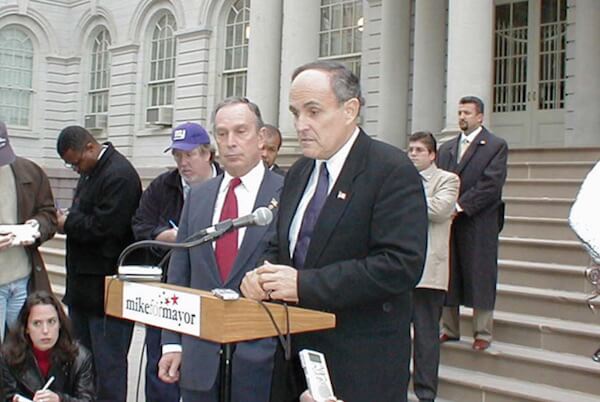

Then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani, in 2001, campaigning for his successor, Michael Bloomberg. | GAY CITY NEWS

Bringing possible finality to a lawsuit bouncing throughout the New York state court system for 15 years, the New York Court of Appeals, the state’s highest bench, ruled unanimously on June 6 that the 2001 amendments to the city’s zoning ordinance governing “adult establishments” do not violate the constitutional rights of businesses that provide sexually explicit materials or activities.

Judge Eugene M. Fahey wrote the opinion, while Chief Judge Janet DiFiore did not take part in the case.

The zoning ordinance was a major project of Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s first term, as he had run for office contending the city had been overrun by adult businesses believed to cause harmful effects to the community.

Nearly a quarter century after ex-mayor’s election, his war on sex shops triumphs

Under US Supreme Court precedents, such businesses cannot be banned outright due to First Amendment protection for expressive activity, but they can be regulated because of the “secondary effects” they cause, such as lowering property values and attracting criminal activity. Local governments can restrict the operation of such businesses by documenting the adverse secondary effects while showing that any regulation leaves enough places where adult businesses can still operate.

Giuliani’s City Planning Department produced a 1994 study of secondary effects of sexually-focused businesses, which “identified significant negative secondary impacts, including increased crime, diminished property values, reduced shopping and commercial activity, and a perceived decline in residents’ quality of life,” Judge Fahey wrote.

In 1995, the City Council adopted a zoning ordinance establishing “regulations barring adult establishments from residential zones and most commercial and manufacturing zones, and mandating that, where permitted, adult businesses had to be at least 500 feet from houses of worship, schools, day care centers, and other adult businesses.”

Those restrictions would have forced most adult business in the city to close down or relocate to remote parts of the five boroughs.

The ordinance applied to commercial establishments a “substantial portion” of which acted as “an adult book store, adult eating or drinking establishment, adult theater, or other adult commercial establishment, or any combination thereof.”

The ordinance, however, did not define “substantial portion,” and some businesses proposed to reconfigure their operations to avoid being labeled as “adult establishments” in order to remain in their existing locations. Litigation ensued, out of which came a ruling by the Court of Appeals upholding the constitutionality of the zoning ordinance.

The city, meanwhile, established guidelines for determining whether a business was in fact an adult establishment, under which those with at least 40 percent of its customer-accessible area or inventory devoted to adult purposes qualified. Businesses responded with a variety of creative reconfigurations — including adding non-sexually oriented stock — to qualify as so-called 60/ 40 businesses and thereby evade the zoning restrictions.

The city cried foul, arguing such reconfigurations did not change the essential character of these businesses, which it began to cite for “sham compliance.” When such businesses again went to court, the Court of Appeals, in 1999, found that having established the guidelines, the city had to live with them. Businesses that technically complied could not be excluded from their locations under the zoning ordinance, the high court concluded.

This, in turn, led the City Council to adopt amendments in 2001, providing that even an establishment that met the 60/ 40 test could be considered an adult business depending on a list of criteria they spelled out. For example, any business operating peep booths would qualify as an adult bookstore, regardless of compliance with the 60/ 40 test.

Business owners then returned to court, contesting the constitutionality of the 2001 amendments. One lawsuit was brought by bookstores selling pornography and sex toys, most of which operated peep booths; the other by nightclubs that provided strip shows and, in some cases, lap dances by performers.

The central argument in these suits was that the 1994 City Planning study could not be used to justify the new definitions of adult establishments because it was conducted with reference to the original zoning guidelines and so did not document the “secondary effects” that the city had to demonstrate in justifying its policy. The owners argued that the alterations they had made substantially changed their businesses, lessening such secondary effects.

This issue first made its way to the Court of Appeals in 2005, after Supreme Court Justice Louis York found the 2001 amendments unconstitutional but was reversed by the Appellate Division, which ruled that a new “secondary impact” study was not required because the plaintiffs’ conversion of their businesses under the 60/ 40 rule had not really changed the sexual character of the businesses.

The Court of Appeal disagreed with the Appellate Division’s approach and sent the case back for further proceedings. In doing so, the high court established a three-stage test for the zoning regulations.

First, the city had to show that it had a “substantial interest in regulating a particular adult activity.” On that score, the 1994 City Planning study did the trick, so the burden was put on the plaintiff businesses to show that the city’s evidence “does not support its rationale.” If the plaintiffs met that burden, the city in turn would have to show that the businesses had not so transformed themselves that they “no longer resemble the kinds of adult uses found to create the secondary effects” in the original study.

The 2005 Court of Appeals disagreed with the Appellate Division, finding that “plaintiffs had furnished evidence disputing the city’s factual findings, shifting the burden back to the city to supplement the record with evidence renewing support for its rationale.”

Since new evidence had to be introduced, the case was sent back to Judge York for more fact-finding — which took until 2010! At that point, York concluded that the city had provided “substantial evidence” that the “dominant, ongoing focus” of the bookstores and clubs was on “sexually explicit materials and activities.”

York rejected the plaintiffs’ argument and upheld the constitutionality of the regulations.

This time, the Appellate Division sided with the businesses, overruling York in 2011 by finding that he failed to specify “the criteria by which [he] determined that the plaintiffs’ essential nature was similar or dissimilar to the sexually explicit adult uses” underlying the 1995 zoning ordinance.

So, the case went back to York, who composed a new opinion, making detailed findings of fact and, this time, concluded that the alterations had, indeed, changed the overall character of the businesses. The plaintiff businesses, he found, “no longer operate in an atmosphere placing more dominance of sexual matters over nonsexual ones.

“On their face,” he found, the 2001 amendments “are a violation of the free speech provisions of the US and State Constitutions.”

This time, the Appellate Division, in 2015, affirmed York, who by then had passed away. In its 3-2 decision, the Appellate Division majority focused on four criteria to determine whether the “60/ 40 businesses” could be considered “adult establishments”: “(1) the presence of large signs advertising adult content, (2) significant emphasis on the promotion of material exhibiting ‘specified sexual activities’ or ‘specified anatomical areas,’ as evidenced by a large quantity of peep booths featuring adult films, (3) the exclusion of minors from the premises on the basis of age, and (4) difficulties in accessing nonadult materials.”

The adult bookstores and the adult clubs had satisfied at least three out of the four criteria, the Appellate Division found, and so should not be considered adult establishments. They had reduced their signage, de-emphasized the sexually-oriented aspects, and fell short only on one aspect of the checklist: they excluded minors from admission.

The dissenters, to the contrary, concluded the city had “sustained its burden as to sham compliance by demonstrating that by and large the essential character of the 60/ 40 businesses has not changed, even if their physical structure has.”

The dissenters, for example, did not buy that bookstores operating numerous peep booths for viewing pornography failed the test of having a predominant sexual focus, even if they had reduced their signage and rearranged their layout to make non-adult materials more accessible. Similarly, they did not believe that an establishment providing “topless dancing by multiple dancers on a daily basis for approximately 16 to 18 hours a day with lap dancing provided in both the adult and the nonadult areas” was not an adult business.

The city appealed, and the Court of Appeals now agreed with the Appellate Division dissenters, criticizing the majority for placing too high an evidentiary burden on the city.

“Properly understood,” wrote Judge Fahey, “the trial court’s task was to decide whether the city had relevant evidence reasonably adequate to support its conclusion that the adult establishments retained a predominant, ongoing focus on sexually explicit activities or materials.”

The Appellate Division majority erred, Fahey wrote, by “applying a rigidly mechanical approach to the determination of whether a predominant focus on sexually explicit entertainment remained… As the dissent observed, the majority’s four-prong checklist, with each factor weighing equally, placed subsidiary considerations such as signage on equal footing with the touchstone issue of emphasis on the promotion of sexually explicit activities or materials.”

Fahey also criticized the Appellate Division for losing “sight of the fact that the issue was whether there was sham compliance. A bookstore could very well engage in such a sham by removing large signs, allowing minors to enter, and ensuring that non-adult materials are accessible, and yet retain a focus on sexual materials. A store that stocks non-adult magazines in the front of the store but contains and prominently advertises peep booths is no less sexual in its fundamental focus just because the peep booths are in the back and the copies of Time magazine in the front. The same is true of the adult eating and drinking establishments. A topless club is no less an adult establishment if it has small signs and the adjoining comedy club, seating area, or bikini bar is easy to access.”

The practical effect of this ruling seems to be that as long as a bookstore is selling porn and operating peep booths, it is going to be subject to the zoning ordinance, and the same is likely to be true of any club providing strip shows, regardless of how it reorganizes its space, modifies its signage, or sets its policies on access by minors.

It is ironic that a nearly-quarter-century litigation battle set off by the moralistic Giuliani administration would be resolved during the de Blasio administration.

The plaintiffs could, of course, yet seek US Supreme Court review regarding the First Amendment implications of the Court of Appeals ruling. But the New York court has traditionally construed the State Constitution to provide more protection for expression than the US Constitution. And the likelihood that the current US Supreme Court would be interested in this case seems rather slim.

Despite the legal wrangling, Giuliani’s efforts clearly had substantial impact in sharply reducing the number of businesses that could be deemed “adult establishments” by any definition. Perhaps the small number of remaining businesses attempting to avoid the zoning rules by rearranging their space, inventory, and activities might consider going back to the political process and the consumers who want to access their goods and services to seek changes at the City Council.

The state’s high court has said the city can do what it has done, but there is no legal barrier to the Council adopting a less restrictive approach.