Judge says Wyoming prison violated due process rights of intersexual woman

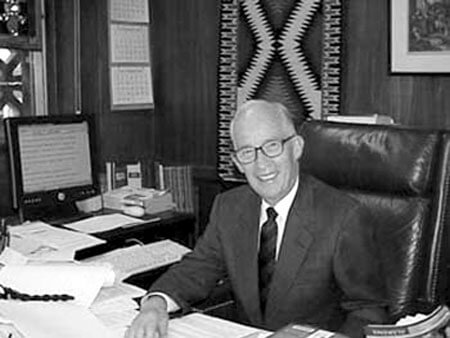

ARTHUR S. LEONARD

U.S. District Judge Clarence A. Brimmer ruled on February 18 that Wyoming prison officials violated the Fourteenth Amendment due process rights of Miki Ann DiMarco, an intersexual prison inmate, when they consigned her to 14 months in a dungeon-like high security lock-up “based solely on [her] gender and physical characteristics” without any hearing for her to challenge that decision.

The ruling may be the first U.S. court decision to consider the constitutional rights of intersexuals.

Brimmer, however, “reluctantly” ruled that prison officials did not violate DiMarco’s Eighth Amendment right to be free of cruel and unusual punishment, and concluded that her claims to equal protection of the laws had not been violated because there was some rational basis for the prison officials’ decision.

DiMarco’s imprisonment is a tale of ignorance and fear, demonstrating the long road ahead for the intersexual rights movement in educating American society. Intersexuals, sometimes called “hermaphrodites,” are born with both male and female characteristics, usually the result of an abnormality of the sex chromosomes or a hormonal imbalance during embryo development.

Beginning in the 1950s, physicians confronted at delivery with an intersexual infant typically told stunned parents that immediate surgery followed by hormone therapy to render the child female was medically necessary, not a matter of choice. In the past decade, adult intersexuals profoundly dissatisfied with the results of procedures they endured as infants formed the Intersex Society of North America to persuade the medical profession to abandon these practices. Doctors increasingly accept the idea that intersexuals should not be subjected to surgery until they are old enough to make informed decisions. (For more information, visit isna.org.)

DiMarco was born with a tiny penis, no testicles, and no female reproductive organs. Without testicles, her body did not produce the hormones that lead to masculinization in body shape and hair, and since puberty she lived as a woman, despite the lack of female reproductive organs. DiMarco, however, never had surgery to remove her penis.

After being convicted of check fraud charges, DiMarco was to receive probation, but she had no verifiable identification and tested positive for drugs, so she was sentenced to time at the Wyoming Women’s Center (WWC). When she arrived at the prison, the discovery of her penis during a medical exam created consternation among the staff. She was immediately assigned to the maximum security wing of the prison, totally segregated from the general population, where she remained for the 14 months of her prison term.

Her living conditions there differed markedly from the those for the general prison population. Brimmer found that conditions in maximum security were like a dungeon. DeMarco had no contact with other prisoners and limited contact with staff, consumed all her meals in a tiny cell, with cement block walls, solid steel doors, and access to a tiny day room with a TV high up on one wall, controlled remotely by a guard. She was given only two sets of prison clothing, unlike five sets assigned in general population, and was not allowed to work for an allowance to buy personal items. She had only brief use of the exercise area, when no other prisoners were there, and could not have her hair cut for 14 months. She also had limited access to books and the deck of playing cards one officer gave her was confiscated after three days. When she conversed with other inmates in her wing, she received disciplinary write-ups for violating the no-communication rule.

DiMarco had been determined to present no risk of violence or rule-breaking to merit maximum security, but the flustered prison staff, uncertain how to treat a woman with a penis, decided to put her in solitary for her own “protection,” and then imposed all the attendant constraints as if she did pose a threat. The prison evaluation that placed her at the lowest possible risk level was “overridden” by the deputy warden “because Plaintiff appeared to be a male in a female institution.”

DiMarco was not afforded a hearing on either the initial classification or the subsequent reclassification evaluations required by prison rules, even though she made repeated requests to be transferred to less restrictive housing. Brimmer found that the prison did not follow its own rules about her right to a hearing.

Prison medical officials concluded that DiMarco was “not sexually functional as a male,” and the warden requested guidance from the state Department of Corrections (WDOC), but such guidance never arrived. Brimmer wrote that the state officials “apparently put their heads in the sand on this issue, and let Defendant Warden Blackburn tough it out on her own.”

However, because of how high the U.S. Supreme Court has set the bar on finding an Eighth Amendment violation for cruel and unusual punishment, Brimmer found, “reluctantly,” that he had to reject this part of DiMarco’s claim. She was housed in sanitary conditions, received three meals a day, was not deprived of sleep, was allowed to exercise, and was not physically assaulted. The Eighth Amendment is only invoked in cases of extreme deprivation of the necessities of life, physical torture of prisoners, or deliberate indifference by prison officials to serious medical conditions.

On the other hand, Brimmer clearly felt that the prison officials had failed to afford DiMarco the minimum procedural fairness required.

“This Court is concerned and alarmed that the WWC staff did not allow Plaintiff to be involved in solving the housing issue through a hearing,” he wrote. “Plaintiff, unlike those involved in a mandatory disciplinary hearing, did not violate prison rules but simply arrived at the WWC with certain physical characteristics that she did not choose.”

Brimmer concluded that DiMarco’s due process rights were violated, that the prison could have made available “better housing quarters” rather than subjecting her to the level of confinement used “for the most dangerous or violent inmates.” He found that even if segregation was necessary for safety reasons, “the prison officials didn’t need to enforce the segregation as if she were a malefactor of the worst kind.”

But Brimmer found no equal protection violation, applying a relatively undemanding test of whether the difference between the prison’s treatment of DiMarco and of other women inmates was rational. He concluded that there was no unlawful discrimination, since DiMarco’s own safety was a rational reason. Perhaps he felt that having ruled for DiMarco on the due process claim in a situation where prison officials were acting more out of ignorance and fear than malevolence, he would not rub salt in the wounds by ruling against them on an additional constitutional basis.

In looking at a remedy, Brimmer heard from medical experts who testified that DiMarco, amazingly resilient, had not suffered permanent psychological injury from this experience, so he imposed only “nominal” damages of $1,000, plus attorneys fees, on the defendants. Given the length and complexity of the trial, those fees, however, are likely to run them many thousands of dollars.

Brimmer ended his decision with an admonition to the prison officials: “This Court also impresses upon the WWC and the WDOC the need to develop a plan and procedures to handle future administrative segregation based upon non-disciplinary issues such as those presented in the case at hand.”