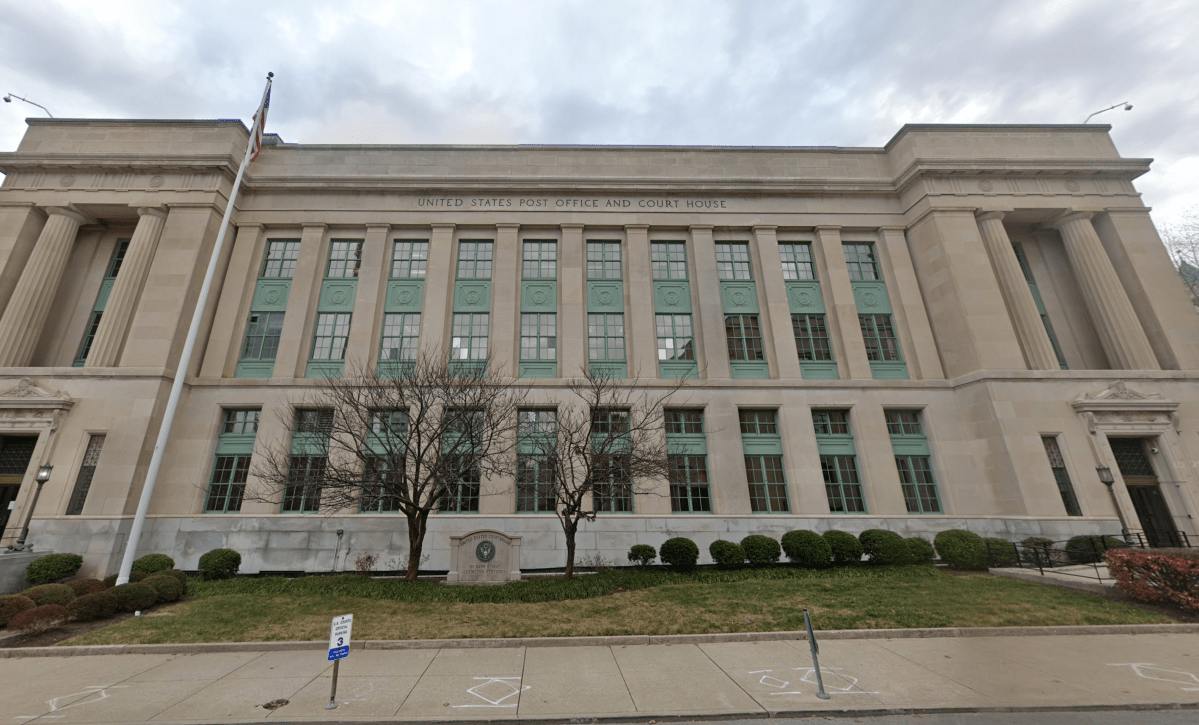

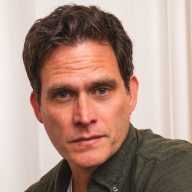

District Judge Danny Reeves of the Eastern District of Kentucky issued an opinion on Jan. 9 vacating the Biden administration’s final rule, adopted by the US Department of Education last June, that interpreted Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 to ban discrimination on account of sexual orientation or gender identity by educational institutions that get federal funds. The rule went into effect in August, but preliminary injunctions issued by seven federal district judges affecting 26 states had already blocked the Education Department from enforcing it in those states while the courts considered whether to strike it down.

During the Obama administration, the Department of Education had followed the lead of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which had interpreted Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to ban employment discrimination because of sexual orientation or gender identity. Responding to those EEOC rulings, the Education Department sent a guidance letter to every school district in the nation explaining that the Department’s Office of Civil Rights would investigate claims of discrimination on those grounds.

When Donald Trump took office, the Education Department disavowed the Obama administration’s approach to this issue, suspending ongoing investigations of discrimination claims by LGBTQ students, revoking the guidance that the Obama Administration had issued.

But that guidance seemed to take on increased strength in June of 2020, the last year of the Trump Administration, when the Supreme Court interpreted Title VII’s ban on sex discrimination to include discrimination because of an individual’s sexual orientation or gender identity. This decision, Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, combined three cases involving two gay men and a transgender woman who claimed they were fired because they were gay or trans. The Trump Administration immediately took the position that the Bostock decision applied only to employment discrimination claims under Title VII, and perhaps only to issues of discharge from employment.

Justice Neil Gorsuch’s opinion for the Supreme Court in Bostock stated, in general terms, that it was impossible to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or transgender status without discriminating, at least in part, on the basis of sex. He observed that it was impossible to describe sexual orientation or transgender status without referring to sex, and held that in the context of Title VII, if sex was involved in an employer’s discriminatory action, that could be held to violate the statute even if sex was not the sole or even primary factor considered by the employer.

Some lower federal courts (and even some state courts interpreted state anti-discrimination laws) began to apply the reasoning from Justice Neil Gorsuch’s opinion to interpret other statutes that ban sex discrimination, such as the federal Fair Housing Act and, in some cases, Title IX, which bans discrimination “on account of sex” by schools. Title IX played a major role in many cases involving the right of transgender students to compete in sports or to use restroom facilities consistent with their gender identity.

When Joseph Biden became president in January 2021, he issued an executive order directing all federal agencies that enforce sex discrimination laws to evaluate whether the Bostock ruling should be applied to the laws the agencies were charged with enforcing. The Education Department promptly issued an interpretive document explaining its approach to Title IX in light of Bostock, and then undertook the time-consuming process required by the Administrative Procedure Act to adopt a final, legally binding rule including sexual orientation and gender identity claims as part of Title IX’s coverage.

It took more than three years after Biden’s directive for the Department to go through the entire APA process to publish a final rule in the Federal Register, slated to go into effect on Aug. 1, 2024. This was partly due to the breadth of the rule that was adopted, which addressed a broad array of issues as to which there was considerable debate, not just the LGBTQ issue. A major focus of the rule is the issue of sexual harassment, including detailed procedures to be used by schools to investigate complaints of sexual misconduct and determine culpability.

As soon as the final rule was published, individual states and groups of states filed lawsuits challenging it, claiming that it was a misapplication of Title IX, a misinterpretation of Bostock, and constitutionally defective. These lawsuits found a sympathetic ear among several federal district judges. Judge Reeves’s Jan. 9 opinion is the first to go beyond a preliminary injunction to render a final judgment holding the rule to be invalid.

His grounds for doing so were numerous, beginning with the slightly different language of Title VII and Title IX. Gorsuch’s opinion said that “because of” meant that as long as sex was a factor in a discriminatory employment action, the employer may have violated Title VII. But Title IX uses the phrase “on account of,” which could be interpreted to mean that sex had to be the sole reason for the employer’s action. In addition, Gorsuch was careful to state in his opinion that the Court was deciding only the issue directly presented by the three cases that were consolidated for argument, which involved the employee discharges. He commented that the court was interpreting Title VII, not any other statute, and was not dealing with a variety of issues that had been raised in amicus briefs, such as which restroom a trans employee could use, or what pronouns teachers would have to use for transgender employees.

These comments were now seized upon by conservative judges as agreeing with the Trump administration’s immediate reaction to Bostock as a narrow decision focused on employee discharges within the specific context of Title VII, which includes various exceptions and affirmative defenses, such as the argument that sex was a “bona fide occupational qualification” for a particular job.

Judge Reeves contended last summer, when he issued a preliminary injunction against enforcement of the rule by the Education Department, that the department exceeded its statutory authority by adding sexual orientation and gender identity coverage to Title IX, although the main focus of his opinions, both then and now, was on gender identity.

Judge Reeves also found a First Amendment flaw. The rule specified that teachers and other school officials must use a student’s preferred pronouns and names. As to this issue, the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit already ruled several years ago that a school’s policy requiring teachers to address students by their preferred names and pronouns violated the First Amendment free speech rights of the teachers, a holding that was criticized and disagreed with by some other courts. But the Sixth Circuit would hear any appeal from a Kentucky case, so Judge Reeves was bound to follow that ruling.

Under the Administrative Procedure Act, an agency has to provide a “reasoned explanation” for departing from its longstanding interpretation of a statute. The Education Department had never interpreted Title IX to cover LGBTQ discrimination claims from its enactment in 1972 until the guidance issued during the Obama Administration in 2016, and the first formal rule to adopt this interpretation was the one published in June 2024. The only explanation provided by the department, however, was that it was following the reasoning of the Bostock decision, which Judge Reeves found to be both incorrect and insufficient as a “reasoned explanation” for a “sweeping new regulation” that would “completely transform” Title IX.

Judge Reeves insisted that the rule creates “glaring inconsistencies” under Title IX, departing from existing interpretations and even some statutory provisions which, in the context of schools, authorized various forms of sex separation, including in social fraternities and sororities at the college level, in separate restroom and locker room facilities, and separate sports teams. He concluded that this rendered the new rule “arbitrary and capricious,” a key term in the Administrative Procedure Act for grounds to strike down a new regulation.

The judge also focused on the fact that Title IX was enacted under the Spending Power of the Constitution, which authorizes Congress to place conditions on the receipt of federal money. When a school agrees to take federal funds, it is agreeing to comply with federal rules, but the courts have held that those rules have to be clearly spelled out in order for the recipients to be legally bound by them. Prior to the adoption of this final rule, those rules had not been adequately spelled out, especially as the court found that the final rule introduced substantial deviations from the rules in effect since 1972.

The APA specifically authorizes a court that finds a challenged rule to be “arbitrary and capricious” to order the rule to be completely vacated and to bar any enforcement of the rule by the government. Judge Reeves rejected the Education Department’s argument that his order in this case should be limited to the issue of gender identity and the handful of provisions in which it is specifically mentioned, finding that as part of the regulatory definition of “sex,” this issue permeated the entire final rule, which is several hundreds of pages long, and that the only appropriate relief is to strike it entirely.

There are no doubts that the incoming Trump Administration was going to repeal and replace this rule in any event, but Judge Reeves’s decision vacating the rule simplifies matters for them because they will not have to go through the process under the APA for revoking or amending an existing rule. They can propose a new rule on a clean slate. The Biden Administration rule is now a nullity.

While it is true that the Education Department could attempt to appeal this ruling to the Sixth Circuit and thence to the Supreme Court, there is only one week left in this administration and the incoming administration will have no interest in appealing this ruling, so rushing to file an appeal before Jan. 21 is not realistic, especially knowing that the new Administration will have no interest in defending the Biden Administration’s rule.

There is a peculiarity about Title IX, however, that keeps this ruling from being a hard stop on all statutory federal protection for LGBTQ students. The courts have long recognized a private right of action under Title IX, which means that somebody encountering discrimination has a choice to sue directly in federal court. They are not required to file a complaint with the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights first, or to let the government undertake its own investigation and possible lawsuit. The loss of the administrative option makes things more difficult for some plaintiffs, but it does not affect their ability to sue.

However, Judge Reeves’s decision poses a barrier because it may prove persuasive to other federal judges who get these cases, and as President Trump placed numerous judicial conservatives on the federal trial and appellate courts, plaintiffs going directly into federal court may find the going rough.

There remain other alternatives. Hundreds of cities and counties and many states — such as New York, New Jersey and Connecticut — have anti-discrimination laws applicable in their public schools, and there is a well-developed practice at times when the federal courts have seemed unfriendly to bring cases to state and local civil rights agencies or courts instead, which are not bound by Title IX cases when interpreting and applying their own state laws and local ordinances. Once the new Trump Administration begins, this is an area in which one would expect to see an increase in the volume of litigation on the state administrative and judicial level.

The first place to go with a discrimination claim would be to the New York State or City Division of Human Rights, or to the state courts.

Judge Danny Reeves serves as the Chief Judge of the Eastern District, Northern Division, of the US District Court in Kentucky. He was appointed by President George W. Bush.