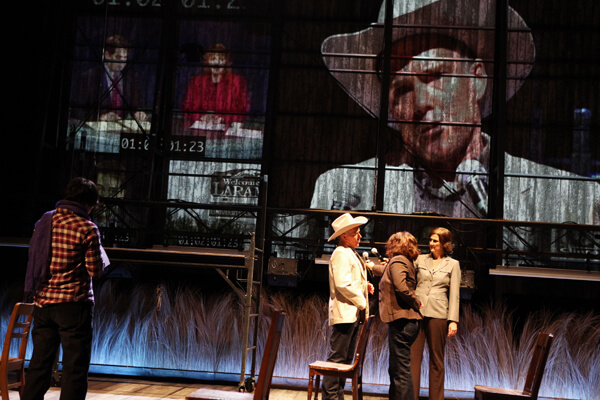

Michael Winther (in hat) and Mercedes Herrero (with mic) in the Tectonic Theater Project's production of “The Laramie Project Cycle” at BAM, through February 24. | JULIETA CERVANTES

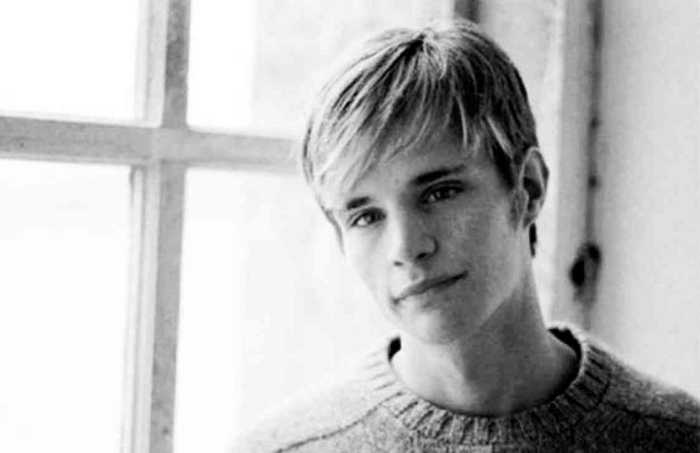

Ten years — especially the decade that followed the 1998 anti-gay murder of 21-year-old Matthew Shepard — is an epoch in LGBT history. BAM’s revival of “The Laramie Project” –– an Off-Broadway play less than successful commercially in 2000 that has gone on to be the most performed play of the period, largely in school productions –– thrusts us right back to the aftermath of that horrific hate crime. Most of the original cast members/ writers from the Tectonic Theater Project are back, portraying themselves as well as the citizens of Laramie who they interviewed when the Wyoming town (population 26,000) was thrown into a national debate over hate crimes against LGBT people.

This complex portrayal of people, a place, and the politics of LGBT rights in the American West is flecked with humor, anger, and diverse, honestly-stated viewpoints, but it is infused with heart and humanity. It has lost none of its shattering theatrical power.

I won’t single out anyone in this true ensemble, but each cast member provides distinct and various theatrical pleasures.

Pair of plays on Matthew Shepard murder's aftermath shine; Matt’s Mom speaks out at pre-show forum

In “The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later,” the same intrepid troupe of theater artists revisits a 13 percent bigger and also more guarded Laramie –– encountering many who are determined not to be defined by the infamous crime, some who have made it a better place for LGBT folks, and others eager to embrace a rationalization of “the incident,” as it is often referred to there, blaming Matt for his own demise.

That last group seizes in particular on an ABC-TV News “20/20” piece by Elizabeth Vargas from 2004 that re-cast the murderers as kids hopped up on drugs and dismissed hate as a motive, despite the brutal overkill to which Matt was subjected –– bashed in the head with the butt of a gun more than 20 times, his young life ebbing away while tied to a fence on the cold prairie. The principal investigator in the case tells Tectonic that the blood samples drawn from the killers debunk the “20/20” assertion they were on drugs at the time. A spokesperson for ABC News this week declined comment on the “Laramie” piece.

This update from Tectonic includes interviews that they did with the convicted men, Russell Henderson and Aaron McKinney. While Henderson is filled with regret, McKinney –– now covered in Nazi tattoos –– feels nothing for Shepard, choosing to believe a lie that Matt preyed on kids and deserved whatever he got. McKinney does not even remember the gay panic defense that he himself used at trial where he tried to justify the vicious attack by alleging Matt made a play for him.

At a BAM forum with Moisés Kaufman, Tectonic’s founding artistic director, prior to the double bill, Judy Shepard, Matt’s mom, who now runs the Matthew Shepard Foundation, talked about how she has made advocacy for LGBT rights her life. She has also tried to rescue her son from a hate crimes victim icon/ saint stereotype with her book, “The Meaning of Matthew,” in which she fleshes out who he was as a person.

She exhorted LGBT people to come out and allies to stand up for us. “Silence equals death,” she said. “I’ve never heard anyone say, ‘I wish I had never come out.’ They say, ‘I wish I had come out sooner.’”

In the audience Q&A, I asked what assessment Shepard and Kaufman have about the efficacy and appropriateness of hate crimes laws, for which they pushed so hard. The 2009 federal Matthew Shepard-James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Act provides federal resources to localities to investigate such attacks, and most laws enacted at the state level add extra prison time for those convicted under them, a feature some of us have come to question.

“We can make it a law,” Shepard said, “but that doesn’t mean it will work.” She said that “what’s important is that it was the first piece of federal legislation that protected the gay community rather than taking rights away,” opening the door to the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and, she predicted, passage of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act and repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act.

“It’s a tool,” she said, “and I wouldn’t care if it was called the Chocolate Cake Act” instead of being named in part for her son.

Shepard called the 2004 “20/20” revisionism on her son’s murder “the worst piece of journalism I’ve ever seen.”

A man named Michael, 34, from Manhattan, spoke up at the forum to say he is the age Matthew would have been now and had followed his story and her journey from the time he was a youth in small-town Ohio.

“I just had to say to you that we couldn’t have had a better mother,” he said tearfully, a tribute that left Shepard and most of the assembled in tears, too.

Kaufman said his goal as an artist is “to make the connection between what happens in life and on the stage closer,” an aim achieved mightily in this pair of plays. Attending out of my sense of obligation as a gay journalist, I was overwhelmed by the continued power of this theater experience and the insight it provides into the –– yes –– tectonic changes in the LGBT rights movement in just the past decade.

“Ten Years Later” portrays a debate in the Wyoming Legislature on a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage. An out lesbian legislator bemoans what she expects will be a losing vote for her until a powerful Republican stands up and turns his colleagues around, warning that a ballot initiative would tear the state apart, dividing neighbors and families and colleagues. The measure fails handily. Before the show, Shepard noted that while Wyoming this month defeated legislation to protect LGBT rights and open civil unions and marriage to gay couples, it did so by surprisingly narrow margins.

Kaufman, who lives on the Upper West Side, said that if a crime such as the Shepard murder occurred two blocks from him, it would not induce the kind of soul searching and scrutiny in his neighborhood or in this city that occurred in Laramie, where everyone is connected to everyone else.

Tectonic’s company of outsiders –– with patience and fairness –– wrested keen observations and characterizations from the people of Laramie. Many would like to put “the incident” behind them now, but they themselves –– in their imperfect coming to grips with it –– will live on as long as there is an audience for this enlightening and challenging work.

The two plays only run at BAM through February 24, though a money review in the New York Times may prompt someone to get it into another house. It’s great theater and deserves that. BAM was filled with more young adults than I have seen at the theater in years, many of them alumni of the nearly 900 productions of “Laramie” –– some in schools where they had to fight administrative censorship to get the gay-themed work staged.

The productions have not only dramatized the dialogue that Matt’s murder started in Laramie, but have often also been vehicles for discussions of local prejudice across the US and beyond.

Full disclosure: The original production of “The Laramie Project,” in 2000, was the first and only play in which I ever invested. I lost it all on its short run here, but am pleased to see the continued vibrant life it has since enjoyed.

THE LARAMIE PROJECT CYCLE: “The Laramie Project” & “The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later” | Tectonic Theater Project | Brooklyn Academy of Music, Harvey Theater | 651 Fulton St. at Rockwell Pl. | In repertory through Feb. 24 | Each show is $20-$80 | bam.org or 718-636-4100