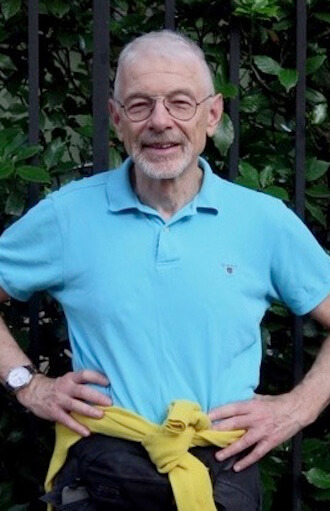

Author Perry Brass. | JASON SERINUS

My father died at the age of 42, when I was 11 years old. I was told he died of “kidney problems.” I was not allowed to visit him in the hospital the last several weeks of his life or to ask questions about him. Questions were completely sidelined by the answer, “You’re too young to understand this.”

It was not until I was 38, at my mother’s funeral, that one of her brothers let this cat out the bag: My father had died of colon-rectal cancer, one of the most inheritable of all forms of cancer. Throughout my younger years, no one had told me the truth about his death. I finally figured it out: growing up in the Deep South, during segregation, the social conventions were that children should not ask questions, especially about such “sensitive” subjects as the body and its various functions. Cancer was an “adult” subject and not one for children, especially a cancer with “rectal” in its name.

The rectum was a completely forbidden area, best sequestered in the bathroom behind several sets of doors. In more polite homes, there was a guest bathroom, but guests would never get to see the real bathroom where the family did what families all secretly did there.

First in a series on gay men experiencing their older years

Happily, we are now in another era. The body, beautiful as it really is, has been brought out of secrecy, shame, and guilt, and this is making aging better. You no longer have to feel ashamed of the body as it ages. Men of my generation, the gay Baby Boomers, have worked hard to see this happen. We’ve been helped by living through the AIDS crisis. Many of us have seen our bodies and the bodies of our friends, brothers, lovers, and now husbands go through changes that people in other eras could not imagine. We have seen them go through a list of HIV diseases, their symptoms, and results.

It has made me feel stronger and better about my own body as it has aged. There is something noble and beautiful about an older man’s body — and his mind — that the gay world is starting to understand. The Bear movement has, in truth, helped this — Bear gatherings, Bear porn, and Bear culture are very much about older men. You have Cubs, of course, but as a group Bears tend to be over 30 or over 40, at least. They are the Daddies we want to be, if we haven’t arrived there already.

Feeling stronger and better about my body has also made me feel differently about aging itself: it is no longer that period once defined as being “pre-death, post-joy.” Although as the old tune goes, “Songs were made to sing while you’re young,” that does not mean that you have to stop singing when you’re old. Or, since “old” itself has still not been struck in our society from the Forbidden Words list, let’s just say “older.”

My feeling about being “older” — and in truth I am no longer “older,” but simply, quite gloriously “old” — is that now is not the time to “act your age,” with all the usual warnings around that, but it is the time to be it. I am now 70 and know it. I have lots of memories that go back 50 years — I will soon be celebrating the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, which I very much witnessed when I was 21, old enough to go to the Stonewall — but I also have a lot to look forward to in the next weeks, months, and years.

One of the things I still like to grab on to is that “can’t wait” feeling of excitement, of wanting something to happen so much you can “taste it.” You need to have that no matter what age you are. When you lose it, well… that’s pretty miserable to me. We can all remember that “can’t wait” feeling from being young; the truth is I don’t want to ever let it go.

So don’t let other people tell you to “act your age,” but be it — be aware of it, own it, with all the richness and hope still in it. And also the sense of humor that age has; it’s hard to take things seriously at this point, there’s too much space around them with real silliness in it.

One of the things I’ve heard about all my life is the ageism of the gay community. How unforgiving it is as far as aging is concerned. Much of this comes from the poison of internalized homophobia, from self-hatred, and a society that either still rejects us or makes it plain that any acceptance of us will have real boundaries around it. I find this to be absolutely true in the Age of Trump: we know that any advances we have made can be either hacked apart or erased by this “moron” (not my word, Rex Tillerson’s) in the White House and his toadies.

What I have understood most of my life is that I am an exceptional person, as are most queer men, and we have to find other sensitive, caring, conscious, exceptional people like ourselves to be happy. The commercial images of us, which get sleeker and more packaged every day, do not include images of men like myself: certainly over 60. But neither does the mainstream, where advertising and most public relations no longer consider us part of the marketing demographic. I like to buy clothes, but I am not installing a new wardrobe every year. Men our age travel a great deal, but travel ads rarely show us, especially gay travel ones.

If you are a single gay man over 60 — or over 70 — many people feel that the possibility of them finding happiness with another man is about “0.” They are either carrying too much emotional baggage with them, or too much weight (literally).

What most people won’t tell you — out of a fear of offense, I guess — is that you might own a lot of baggage from your past, or even what’s going on in your present, but you don’t have to take it all out with you. The more successful older men I know have either been born good listeners or learned to cultivate that talent. Younger men are starved to have someone listen to what they have to say — most of the time people their own age are too full of themselves even to shut up for a second.

So there is something wonderful about being smart enough, and wise enough, to just shut up and listen. And also, it can be really gratifying. As a writer, I am a trained listener, but socially it is wonderful to be in the company of older men who are secure enough to do it. They don’t have to bring out every opinion in the world they have; they can actually listen to yours. When I was considerably younger, I was drawn to men like this, the ones who did not have to be magpies all day. I found myself so drawn to them that I became literally hungry to be in their company. What I often found so wonderful about them was that despite having a very well drawn life of their own, they could open it up enough to invite in other people, especially someone younger like myself.

Looking back on me, I can easily say I was not the easiest person to deal with, having hard opinions of my own — things that, as you get older, do start to unravel, even in these opinionated times — but I found men who could really listen to me without harsh judgments to be extremely valuable, and sexually interesting. In short, sex needs to be tied to the opening of the soul and people who are receptive to it.

That question of what is a “soul” is something a lot of us older men really go through — maybe from just being closer to it in one way or another. It is not hard for me to define what I think a “soul” is (I always felt it was that place of the deepest part of the imagination, which does not mean at all that it is imaginary), but strangely, with age the route to it gets bigger and bigger. It is approachable in so many ways so that when two people share it, it opens up a vast vista. The soul can be something or someone that is physically beautiful, and it also can be something or someone that allows our own beauty to come forward.

Some men find that the way to it needs to be a bit rocky, involved with fetishism or leather or a more stringent view of God or a strictly shared approach to feelings. But mostly what a large number of men want is some sense of protection, of that safe harbor for themselves after the turmoil of city or contemporary life. That sense of protection you can offer anyone is a huge gift. Remember that.

And you don’t have to be young to offer it. I know that.

This is the first in a series of articles by Perry Brass on gay aging. Future pieces in the series will explore loss and not being alone, housing solutions, sexuality and its changing formats, among other issues. Perry Brass’ 19 books include the novels The Substance of God, Carnal Sacraments, and King of Angels, and the classic gay self-help book How to Survive Your Own Gay Life, as well as The Manly Art of Seduction, and The Manly Pursuit of Desire and Love. He is currently working on a book about gay men facing the future in this uncertain time. He can be reached through his website, perrybrass.com or on Facebook.