When what would become AIDS started showing up in New York in the late 1970s, only a handful of doctors did something as simple as putting two and two together and spotting a pattern. Dr. Joseph Sonnabend, a medical researcher with a practice of mostly gay men in Greenwich Village, was the first in 1979 to try to sound the alarm and get health authorities to pay attention.

Neither the City Department of Health, to whom he reported the phenomenon — and where he had worked as Director of Continuing Medical Education at the Bureau of VD Control with an emphasis on gay sexual health — nor the CDC took any action until mid-1981, by which time the syndrome had become an epidemic, eventually blossoming into a worldwide pandemic that has killed 35 million people and infected an additional 35 million.

Many, however, were saved from death by the early actions that Dr. Sonnabend and a few of his colleagues took at the outset, fighting off the double whammy of an unresponsive public health establishment and a bigoted society content with the illness and death of those in the initial “risk groups” — gay men, and then injecting drug users, most of whom were people of color.

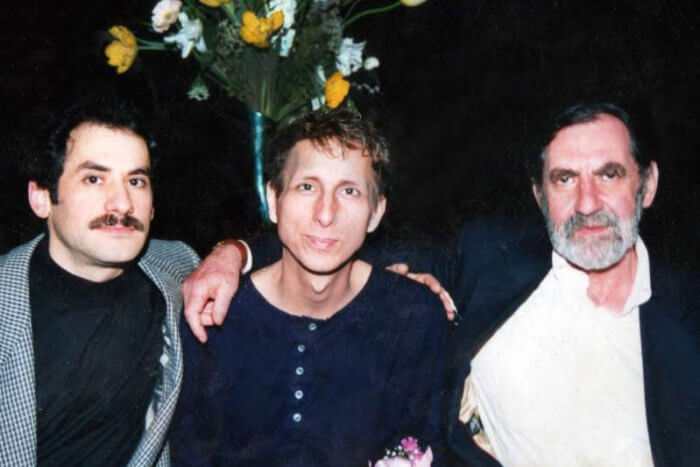

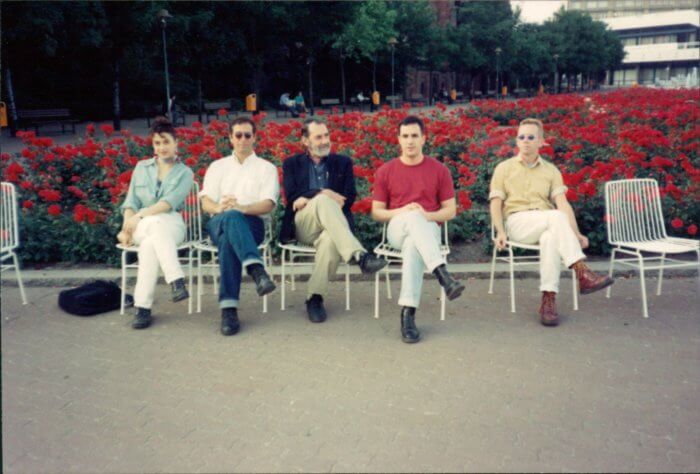

Dr. Sonnabend, a native of South Africa who grew up in what is now Zimbabwe, trained in London, and did most of his work in New York City, died on January 24 following a heart attack earlier that month in London — where he had moved in 2005. He was 88.

“He saved hundreds of thousands of lives by treating opportunistic infections, especially PCP [the pneumonia hitting most early cases], with prophylaxis of Bactrim,” said David Kirschenbaum, his close friend and co-executor. For several years, the CDC resisted making this standard treatment for people with the syndrome — initially called “GRID” for gay-related immunodeficiency — for lack of clinical trials. The pneumonia abided as the number one killer of those diagnosed.

Dr. Sonnabend, who was openly gay, was working with Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien at NYU as the first cluster of cases in New York and Los Angeles were being tracked. Dr. Larry Mass, who went on to become a co-founder of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1981, was the first to write about what was headlined “Cancer in the Gay Community” for the New York Native, a gay newspaper, in May 1981 referring to the skin cancer, Kaposi’s Sarcoma, that was felling gay men along with PCP. The CDC included the early reports in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly on June 5, 1981 and the New York Times ran a brief story on July 3 that shook the gay community even though the cause remained unknown.

Before the emergence of AIDS, Dr. Sonnabend had been a volunteer at the Gay Men’s Health Project — a clinic in Sheridan Square where gay men (including this reporter) got routine screenings for sexually-transmitted infections. There and in his private practice, he saw STI rates skyrocketing in the newly-liberated community just a little over a decade after the Stonewall Rebellion.

Government response to the syndrome was non-existent to slow at first under Mayor Ed Koch in New York City and, of course, under President Ronald Reagan. Despite the fact that he had access to patients and expertise in virology, Dr. Sonnabend was sidelined by the initial researchers. Dr. Sonnabend — along with Dr. Mathilde Krim, a friend he knew from earlier work on Interferon, and his AIDS patient Michael Callen — took initiative and co-founded the AIDS Medical Foundation in 1983. That eventually merged with National AIDS Research Foundation in San Francisco to form AmFAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, in 1985, with the pioneering advocate Elizabeth Taylor serving as its national chair.

Dr. Sonnabend left AmFAR’s Scientific Advisory Committee in 1985 over his objections to their over-emphasis on female-to-male transmission, which he felt they were doing for fundraising purposes rather than grounding it in science.

He faced — and overcame — adversity for his willingness to treat people living with AIDS. His office’s co-op sought to evict him, but on behalf of five of his patients, he brought a landmark discrimination suit in 1984 that protected them and those who served people living with AIDS.

Dr. Sonnabend was a pioneer in community-based research, founding the Community Research Initiative (now ACRIA) in 1987 and editing the journal “AIDS Research” from 1983-86.

Before HIV had been identified as central to the syndrome, Callen, who died in 1993, and Richard Berkowitz, who is still with us at 65, wrote “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach” in 1983. Writing in the foreword, Dr. Sonnabend noted, “Perhaps the most important message contained in this pamphlet is the authors’ premise that when affection informs a sexual relationship, the motivation exists to find ways to protect others from disease.”

They favored a “multifactorial theory” of what caused AIDS. In the absence of the discovery of a new agent, they emphasized limiting exposure to CMV (cytomegalovirus) or the Epstein-Barr virus — which were common among people living with AIDS. Through this work, the campaign for safer sex was born.

Once HIV was discovered, Dr. Sonnabend remained skeptical that it alone caused AIDS, but he was no HIV denialist. When combination antiretroviral treatments became available, he prescribed them readily, though in the absence of symptoms, he held out for a time on providing them immediately after an individual tested positive for HIV.

In 2014, Dr. Anthony Fauci, who sometimes tangled with Dr. Sonnabend, praised him in a POZ profile by its founding editor, Sean Strub.

“[Dr. Sonnabend] is one of the true soldiers in the war against HIV,” Fauci said. “He is a model for a real translation of care to the patient. In terms of the controversy surrounding his work, I think, in general, at the end of the day, most would agree that his contributions have been positive. He is an outstanding man.”

In that article, Strub offered his personal experience as a patient of Dr. Sonnabend.

“I’m one of the dying he has kept alive,” Strub wrote. “Not through some magic combination of pills he urged me to take, but through an intangible conveyance of hope, respect, trust and — ironically — through urging me not to take certain pills. Since my diagnosis, I’ve outlived three of the four doctors I had before Sonnabend, each of whom, while caring and compassionate, had sought to prepare me for my eventual death from AIDS. Joe was the first to prepare me for survival.”

In 1987, Dr. Sonnabend, Callen, and Tom Hannan co-founded the PWA Health Group — where I served on its first board — to get promising treatments to people living with AIDS that “might help and couldn’t hurt” and had yet to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It was the among the first “buyer’s clubs,” much like the Dallas Buyers Club of Ron Woodroof that sprang up around the same time. Dallas Buyers Club led to the 2013 film that yielded an Oscar for Matthew McConaughey’s portrayal as Woodroof and Jared Leto’s role starring as Rayon, a fictional transgender person with AIDS. Hannan, an opera singer and activist, died in 1991.

“One of Joe’s most important contributions was his belief — that he conveyed to his patients — that AIDS would not be 100 precent fatal, that no matter how bleak the prognosis, some people would ultimately survive,” Simon Watney, a writer, activist and close friend of

Dr. Sonnabend’s, said in a release. “That provided powerful hope at a time when hope was in short supply.”

In a 1998 profile, Strub wrote, “The environment (in his office) was such that patients in the waiting room sometimes rearranged the order of seeing Joe, based on our collective assessment of who needed to see him first, or who had other doctors’ appointments to get to. Joe’s patients are protective of him. Those of us with insurance remind him to send out bills; those without often helped in his office, cooked him dinner or volunteered with the organizations Joe started. Over the years, his patients have redecorated, filed, cleaned and helped in the management of his practice.”

Kirschenbaum, who went on to co-found the Treatment and Data committee at ACT UP with Iris Long, said, “When thinking of all his accomplishments and contributions to saving lives during the AIDS crisis, one cannot separate Joe the scientist/physician from Joe the man. His compassion for humanity was the driving force behind all that he was able to achieve in medical research. This is why he eschewed the spotlight which he so rightly deserves.”

Dr. Krim said of him in POZ, “What did Sonnabend contribute? He contributed me. He was the one who alerted me to the problem. I remember the day in the early ’80s when Joe came to me and said, ‘I’ve lost my stature as a physician. I have patients with big lymph nodes and high fevers, and they don’t get better. What’s strange is they’re all young, gay men.’ He’s the only doctor I know who goes to every funeral. From the beginning, Joe said the government was wrong to give money to academic clinical research — people who had no contact with the disease.”

Dr. Sonnabend received numerous awards over the course of his life, including the Award of Courage from AmFAR in 2000 and the Red Ribbon Leadership Award from the National HIV/AIDS Partnership in 2005 in London. He was also a composer of classical music and made his debut at 85 with a sold-out concert at London’s Fitzrovia Chapel as part of an AIDS Histories and Cultural Festival.

The reason Dr. Sonnabend moved backed to London was to take care of his sister Yolanda Sonnabend as she battled dementia. Their nephew, Thomas Burstyn, made a documentary about their time together, “Some Kind of Love.” The trailer is here.

Activist and long-term HIV survivor Ivy Arce wrote in an email that she had been a patient of Dr. Sonnabend in the 1990s.

“Last year during COVID-19 lockdown I reconnected with him and he told me that he had archives in several places — the New York Public Library, in England, and he also had some documents that he gave to the LGBT Center Archive. In one of his trips back to New York he found out that the Center had gotten rid of his archives, that they were shredded and that they had wanted Joe to pay them storage fee. He was very angry about it. The Center could have reached out to him and returned them. But they didn’t and chunks of that history is gone.”

He was pre-deceased by his sister, Yolanda Sonnabend, a prominent theatre designer and artist.

A funeral for Dr. Joseph Sonnabend in London is Wednesday, February 17 at 2 PM GMT (9 AM EST) and will be webcast live and archived a week later for 28 days. Go to this website and sign in with Username: Ralo5642 and Password: 575470. The service will be archived online from February 24 to March 29 using the same login information.

Dr. Sonnabend’s interview for the ACT UP Oral History Project is here.

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.