Way back on March 8, Leigh Whannell’s “The Invisible Man” was the last film I watched in a theater. Knowing how the following months would pass, its conceit of an invisible villain stalking a woman who can’t rely on authority figures for protection proved resonant in ways even the enthusiastic reviews it received in the spring couldn’t predict. Over the past six months, horror films’ vision has generally rung truer to me than the world views of our politicians or media.

Most of the films that hit home in 2020 had some connection to the circumstances under which we have to watch them now. For instance, Charlie Kaufman’s “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” devotes half of its time to a couple arguing while trapped in a car driving through a snowstorm. In 10 years, this image will mean something different, but who can achieve some objective distance from our altered sense of time and atomized communities? Movie theaters have re-opened in 70 percent of the US, but not New York State.

Just before I began writing this article, Film Forum joined with 16 other independent theaters in the state to urge Governor Andrew Cuomo to allow them to return to business, arguing that their ability to stay afloat is on the line. But where theaters were open even the promise of Christopher Nolan’s “Tenet,” touted as the first post-COVID blockbuster release, didn’t seem to get audiences willing to risk catching the virus for two and a half hours of entertainment.

So what does it mean to mount a film festival under these grim circumstances? If you’ve attended enough arthouse screenings with audiences that can be counted on both hands and then come home to see online discussion of the latest Netflix hit, the idea that a meaningful communal experience can only be had in a theatrical space has taken some blows.

The 58th New York Film Festival has turned to drive-ins as a supplement to streaming. Oscar bait is mostly missing from this year’s programming. (For instance, they passed on “Good Joe Bell,” in which Mark Wahlberg acts up a storm as the father of a gay teen who committed suicide.) Film at Lincoln Center and MoMA canceled their New Directors/ New Films festival, which was supposed to take place last March. But in the absence of name directors, the New York Film Festival has made room for films that might play ND/ NF in an ordinary situation, like Dea Kulumbegashvili’s “Beginning” and Yulene Olaizola’s “Tragic Jungle.”

NYFF also made a policy of opening the Main Slate up to documentaries rather than restricting them to their own sidebar. Away from titles likely to get mainstream press, Simon Liu and Jennie MaryTai Liu’s “-force-” is an outstanding Hong Kong cyberpunk dystopia short with blown-out colors and a queasy vaporwave soundtrack, playing on the “Free Radicals” program in the “Currents” sidebar.

The programming this year reflects the world around it, where Black Lives Matter protests have been raging for the past few months. (John Waters’ poster for the festival alludes irreverently to debates about diversity in film culture. He is also presenting a drive-in double bill of Gaspar Noé’s “Climax” and the gay director Pier Paolo Pasolini’s infamous 1975 “Salò.” Take the whole family!) The first Black director to make a Best Picture Oscar winner, Steve McQueen landed three-fifths of “Small Axe,” his BBC/ Amazon anthology series about Britain’s Afro-Caribbean community — “Lovers Rock,” “Mangrove,” and “Red, White and Blue” — in the festival.

The documentary selection includes “MLK/ FBI,” which explores the bureau’s harassment of the now-sanitized civil rights leader, “The Inheritance,” a hybrid film based on Philadelphia’s radical Black MOVE collective, “Her Socialist Smile,” which resurrects Helen Keller as a leftist hero, and “The Monopoly of Violence,” an anarchist critique of the French state’s authoritarianism.

Films by LGBTQ directors include Tsai Ming-liang’s “Days,” Matías Piñeiro’s “Isabella,” and Pedro Almodóvar’s short “The Human Voice.” Will the festival’s online orientation this year make these films more accessible to audiences who are more marginalized than the well-to-do crowds who have usually turned up for the festival’s expensive in-person screenings?

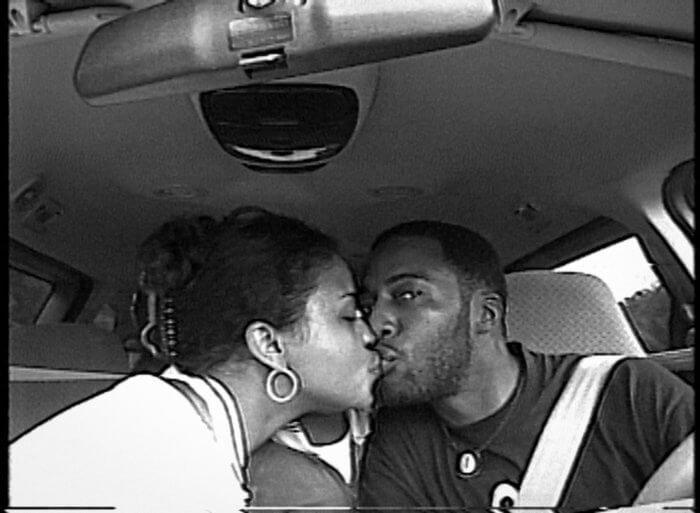

The festival opened on September 17 with McQueen’s “Lovers Rock.” Until now, his features have all incorporated a large dose of suffering. His work is filled with a Catholic sensibility suggesting that our bodies have to experience pain, maybe even torture, for spiritual progress. Set around 1980, “Lovers Rock” goes in a new direction, using the made-for-TV format to work as a miniature and exuding a warm, celebratory spirit.

Set over the course of 24 hours and mostly taking place at an all-night reggae dance party for the Afro-Caribbean community in a private house in London, it’s a much more upbeat counterpart to Olivier Assayas’ “Cold Water.” Although told through medium shots and close-ups, its cinematography and direction are sensual and immersive. A tension between an individual’s story and a style more concerned with collective experience runs through it.

“Lovers Rock” follows Martha (Amarah Jae St. Aubyn) through the party as she rebuffs obnoxious men and meets a potential lover (Micheal Ward.) But its centerpiece abandons narrative entirely to show women dancing to Janet Kay’s “Silly Games” for several minutes and singing it acapella after the DJ takes the record off. Later on, the film includes an all-male variation on that scene, as the room almost becomes a mosh pit while dancing to the Revolutionaries’ harsh dub instrumental “Kunta Kinte.”

British critic Ella Kemp responded to it by simply writing “I miss parties.” “Lovers Rock” finally suggests a transcendence from the pain depicted in McQueen’s earlier films, without dismissing the facts of racism and violence.

“Lovers Rock” plays at the Bronx Drive-In on September 23 at 8 p.m. and will become available again for streaming from the evenings of October 3-5. McQueen’s entire series streams on Amazon Prime in October, as well.

The name of Garrett Bradley’s documentary “Time” signposts its ambition. Just as narrative films released under COVID like “Tenet” and “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” question the linear nature of time, Bradley does so in a far more politicized way. It collapses several different stories, all overlapping but taking place in different time frames. In the present, Sibil Fox Richardson’s hopes that her husband, imprisoned for 21 years after committing a robbery, will be granted release by a judge. But Bradley edited new footage with rough-looking mini-DV videos shot over the much longer period where she struggled to free him and raise her family.

The entire film is in black-and-white. The common notion that incarceration of Black men is a modern-day form of slavery gets brought up several times, putting the Richardson family’s sorrows in a much larger context. Even the score, composed by Jamieson Shaw and Edwin Montgomery, makes a link to the past via Thelonious Monk-influenced solo piano passages.

Like Khalik Allah and RaMell Ross, Bradley makes documentaries that implicitly question the ability of conventional film form to render Black life truthfully. (Her 2019 short “America” made such a splash that it got a week-long run at BAM, and MoMA is presenting a retrospective of her work, which includes multi-channel installations, in November.)

The editing of “Time” is impressionistic and subjective, instead of telling Richardson’s story from start to finish with no digressions. By all measures, she made a success out of her life, raising a son who graduated high school at 16 and got accepted to a prestigious college. “Time” asks what she — and other Black women — could have done without the immense burden of American racism and its enforcement via the carceral system.

“Time” streams Sept. 20 at 8 p.m. through Sept. 25 at 8 p.m. It also plays the Brooklyn Drive-In coinciding with its streaming premiere. It will then become available on Amazon Prime in October.

With “I Carry You With Me,” director Heidi Ewing makes her first step into the world of narrative features. (Its Spanish title “Te Llevo Conmigo” also appears onscreen.) This love story between two Mexican men, Ivan and Gerardo, contains a strong element of non-fiction, with actors playing the main characters as children and young men and years’ worth of real footage of them in present-day New York edited together.

I would love to say that Ewing’s venture away from her comfort zone — together with her filmmaking partner Rachel Grady, she’s been making acclaimed documentaries since 2005 — paid off, but “I Carry You With Me” is only really successful when she works with the real Ivan and Gerardo. The script she wrote with Alan Page Arriaga stuck closely to their lives, but paradoxically, reality can play as a series of clichés about homophobia and xenophobia when turned into fiction. (For instance, one can guess that Gerardo and his transgender friend will eventually get gay-bashed while walking down the streets of their town long before it actually happens.)

The constant use of Jay Wadley’s ambient score feels manipulative, even if the actual music is fairly quiet. Ewing’s style relies on hand-held close-ups, with her camera sticking to the actors. The film does bring a welcome warmth to these immigrants’ stories, but until it arrives in New York, its juggling of time frames and actors is more awkward than lyrical. Part of the issue may be that Mexican movie stars Armando Espitia and Christian Vazquez, cast as the 20-something Ivan and Gerardo, can’t help bringing glamour to a story otherwise striving for grit and realism. The real Ivan and Gerardo are simply better at performing their lives for Ewing’s camera. But “I Carry You With Me” does become a great deal more ambiguous and lyrical in its last half hour than one might expect from its unpromising start.

“I Carry You With Me” plays at the Queens Drive-In at 8 p.m. on October 2 and streams on that day from that time until midnight. It will open in January 2021.

Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-liang’s films have always offered a gloomy — and often downright bleak — view of humanity’s ability to transcend our individual selves. His latest film, “Days,” is no different. At first, its two characters act out disconnected lives in two separate cities, coming from different countries. The muse for Tsai’s entire career, Lee kang-sheng plays a variation of himself (suffering from his real neck pain problem) in Hong Kong. “Days” also traces Laotian immigrant Anong Houngheuangsy’s life in Bangkok.

Tsai’s version of slow cinema is ill-suited to viewing on a laptop (although seeing a film this oblique and austere at a drive-in sounds like a joke from a John Waters film), with Houngheuangsy posed at the back of the frame in long shots. But “Days” uses sound design brilliantly to create variation in long, Warholesque close-ups of its two actors and to suggest a thriving urban landscape beyond its characters’ small worlds. When they meet up, the film finally develops an emotional pull.

Even more so, “Days” becomes one of Tsai’s most sexually charged films. (The director’s images of Lee receiving a massage ending with anal sex are as erotic as the male gaze ever gets.) The kind of isolated urban spaces depicted in “Days” existed long before COVID, but the desperation on Lee and Houngheuangsy’s faces has a new urgency now that the chances to make connections outside online spaces have dried up.

“Days” plays the Brooklyn Drive-in at 8 p.m. on September 25 and streams at 8 p.m. from September 25-30. It will be released next year.

58TH NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL | Through Oct. 11 | Streaming at https://virtual.filmlinc.org/ ; screening at Brooklyn Drive-In at the Brooklyn Army Terminal, 80 58th St. at First Ave.; Bronx Drive-In at the Bronx Zoo, 2300 Southern Blvd. at E. 182nd St.; Queens Drive-In at the New York Hall of Science, 47-01 111th St.