When Karl Dunn married his husband, he thought he had everything he wanted. He had a great job in advertising, a trophy home in Los Angeles, the right clothes, the right car, and what he called a “bear god” in bed with him at night.

And then it all went wrong.

Or perhaps, not all, but Karl realized that he wanted — needed, really — was to get divorced. However, that turned out, as he said in a conversation with Gay City News, to be a “minefield.” That simple request to end his marriage ended up sending him on a journey, which, while torturous, harrowing, emotionally devastating, and excessively complicated (and, no, that’s not an exaggeration), also stared him on a journey of discovery. It turned into a spiritual quest of sorts, and Karl ultimately found the life he wanted to live…rather than the one he felt he was supposed to be living.

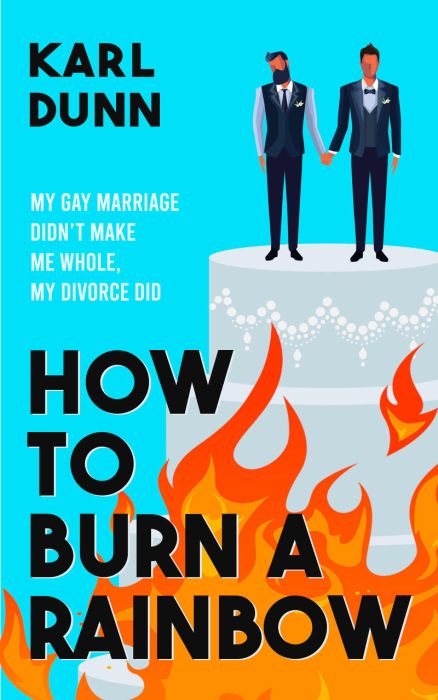

Karl has captured his journey in a remarkable new book, “How to Burn a Rainbow.” Certainly, he chronicles the trials (literal and figurative) of a divorce, which were an awakening in and of themselves. For example, the divorce laws in California were written to protect the lower earner — typically a wife with dependent children. They say nothing about two people of the same gender and their often very different situation. In Dunn’s case, that was used against him, leaving him virtually penniless. (If nothing else, Dunn would advise you to be aware of the divorce laws in your state before tying the knot, as unromantic as that might seem.)

It is, however, Karl’s spiritual recovery that becomes the centerpiece of the book, and he writes with honesty and self-awareness about gay culture and himself as a gay man. At one point, he writes out five reasons why he chose to get married, from doing it “for the cause because we could,” to the more emotional need to hope to hold onto a partner. As he analyzed his reasons, Karl realized that none of them were really any good, and the one that seemed practical — the tax breaks for married people — was completely negated by the cost of the divorce.

And while Karl’s impulse was to move on and “jump into the next thing,” he managed to pause and look inside. He was lonely, but he also had to confront that those feelings were propelled by deeper insecurities that nobody wants to think about.

“No one wants to have that conversation with themselves in the mirror,” Karl said. This was my crisis of identity for better or worse. And there was a point where I’d just gone out so far, there was no way I could go back. I was so far from shore. I didn’t want to go back to being a person I didn’t want to be any more. And yet, when you embark on a journey into the unknown as I did, guides will show up.”

Karl’s guides took the form of friends he met in Berlin, others in Los Angeles, and people who had been through their own transformative processes. Like a good journeyman, he took pieces from other disciplines, such as 12-Step programs and Buddhism. He calls the book “the collected wisdom of more than one hundred people,” from all walks of life — many of them surprising.

One of the most surprising things on his journey was the kinship Karl ended up feeling with divorced, straight guys. “Divorce straight guys saved me. If you are LGBT and you are going through a divorce, find the straight people at work who’ve been through it. They will save your lives.”

Among other hard lessons, Karl had to learn to be present in the moment, to the extent possible, and accept whatever was going on. He describes the text he received from a friend after Karl had been very upset about something in the divorce that simply said, “This is what it feels like to be Karl today.”

He also writes about a friend who encouraged him to see his own part in everything that happened, to take what he calls “radical responsibility” for all that happened in his life so he could no longer play the victim. Hard as that was, it was also liberating.

Karl writes with such feeling and such honesty that issues common to many spiritual practices — such as striving to be present, let go of the past, and accept life on its own terms — become visceral for the reader. It’s not just empathy we feel, though; it’s identification.

“I think what this journey taught me more than anything is, is not only to find myself, know myself, love myself, despite for all my imperfections…to love all of that.”

And as Karl says, the journey continues. Karl is embarking on a speaking tour to share his experience, which he says starts, with “Hi, everyone, I’m here with bad news…” Of course, he’s joking, and the universality of this powerful book and it’s message of hope — and doing the hard work it requires — is ideal for all of us.