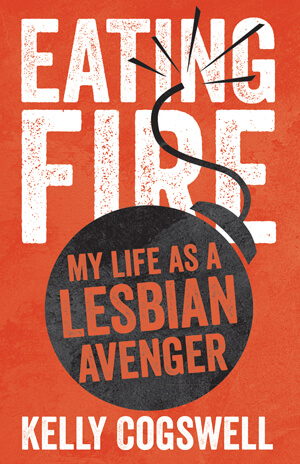

BY KELLY COGSWELL | Since my book “Eating Fire: My Life as a Lesbian Avenger” came out, I’ve had people getting all freaked about how often I use the word “dyke,” which in my vocabulary is almost interchangeable with lesbian. It’s not just straight people that get squeamish. There was this young — gay woman? — that apparently had only heard bigots use “dyke.” Though for the record, she could barely utter the word “lesbian” either, and just talked vaguely about girls.

For a while now, “RuPaul’s Drag Race” has been attacked over language, and recently the show was persuaded to quit using a controversial “she-mail” gag. Critics are also trying to get the word “tranny” banned, condemning anybody that uses it, even somebody who considers themselves trans or has a clear drag queen identity.

I’d always thought the unspoken rules for reclaiming epithets had to do with who the speaker was. If some young black kid wants to call his pals “niggahs,” who am I to judge? As a white chick, they’d laugh in my face, anyway, the same way they sneer at those members of the African-American community who go all ballistic when they hear the word. No, the generation who uses it just ignores them and goes on about its linguistic business.

Likewise, I can say the word “dyke” as much as I want, with affection or bitter rage, admitting it often sounds wrong in other mouths — even when they don’t turn it into a curse. Words bristle with their histories. I spent half an hour at a party once explaining to a gay white guy why it was a bad idea for him to use the n-word. “But they do.” “So?” “They even call me that, sometimes. Why shouldn’t I use it?” And I gave him my speech.

But lately, I’ve realized I break my own rules. For instance, I’ve often used “fag”, even though I’m not one. I’ve even occasionally said “tranny”, though under very restricted circumstances. And not lately. So either words like “dyke” and “fag” don’t function quite the same as “nigger,” or I’m a big fat hypocrite. Neither is out of the question.

It helps if you know that for a while, anyway, during homo prehistory, a lot of us used those words in New York’s LGBT activist community. Yeah, those were the days when “queer” might have described a three-dollar bill, tattooed dyke, or bewigged, high-heeled man, not a university program for earnest undergrads carrying around volumes of Judith Butler.

Referring to ourselves as dykes, fags, trannies, queers actually meant something specific. More than reclaiming the bigoted slurs and embracing our pariah status, we signaled our refusal to settle for the crumbs of mere tolerance or pained acceptance. And this was a lot more than a radical pose. We were the fags from ACT UP, dykes from Queer Nation or the Lesbian Avengers, trannies like Sylvia Rivera that would emerge sometimes in groups like STAR (originally Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, until Transgender was substituted).

And, yes, we sometimes used those words to refer to each other. It was a sign of recognition. An acknowledgement we had something in common, mostly that we couldn’t, wouldn’t pass in polite society. In fact, we’d burn down the whole rotten structure the first chance we got. So if you were organizing an anti-violence march, you’d make sure to issue a call to all your dyke and fag friends. (Even among us, transfolk were often marginalized). But clearly excluded were all the nice LGBT people who were horrified at the noise we made, our unseemly low-class obnoxious behavior, the arrests we racked up, our refusal to fit in as we fought AIDS, violence, and homophobia.

One difference between then and now was that our audience knew what the words meant. Like some stories that fail in the re-telling, maybe you had to be there. Code-switching, changing your vocabulary, your style is a tactic for everybody outside the hegemony of power. Sometimes, we’d use those words in our speeches and put them on banners. But not always. For public consumption, our spokespeople stuck to Standard White English, talked about lesbians and gay men.

If the language of “Drag Race” offends some, maybe it’s because there’s no context, or history. You get the insider words without any of the political edge. “Tranny” seems more like a joke than an act of resistance. What troubles me is how far their critics are willing to go — forbidding even drag queens from using a word that was commonly used in their own community. And given the history of the LGBT movement, this outcry seems less like a battle against transphobia than one more attempt by the usual enforcers to keep troublesome dykes and fags and trannies in line so that one day soon, straight, white, middle class America will throw open its arms and welcome its dignified (Stepford) children home.

Kelly Cogswell is the author of “Eating Fire: My Life as a Lesbian Avenger,” published by the University of Minnesota Press.