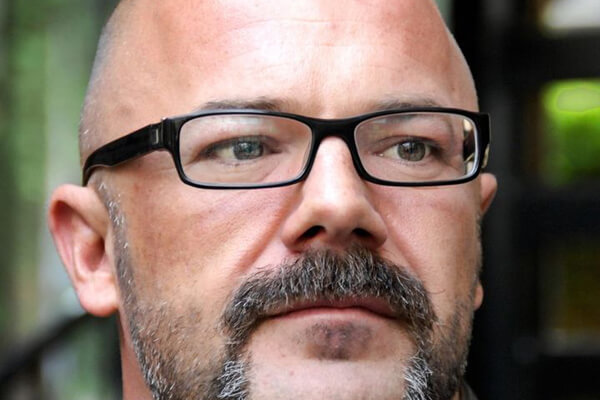

While chastising the Romney campaign for its refusal to defend Richard Grenell, an openly gay spokesman who resigned his position, from right-wing attacks, blogger Andrew Sullivan argued that if gay marriage supporters, such as Grenell, were barred from serving in Republican campaigns, that meant that all gay conservatives were effectively shut out of such campaigns.

Sullivan then asserted that it was gay Republicans and gay conservatives who launched the movement for same-sex marriage.

“Marriage equality started out as a conservative revolt within the gay community,” Sullivan wrote in a May 2 post on his Daily Beast blog. “Gay conservatives and Republicans helped pioneer gay marriage as an issue to some serious pushback from the gay left at the start.”

That would be news to the roughly 100 lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people who gathered in Chicago in 1972 for the first and only meeting of the National Coalition of Gay Organizations (NCGO). Representing 85 groups from 18 states, attendance was dominated by members of the Gay Activists Alliance and the Gay Liberation Front, two far-left groups.

Among the NCGO demands were the right to marry, though they opposed restrictions on the number of people who could enter into one marriage, and an end to discrimination based on sexual orientation in military service.

Sullivan has long claimed to be the founder of the gay marriage movement, along with Evan Wolfson, the president of Freedom to Marry, and he repeated that view in an email to Gay City News.

“The campaign for marriage was always there, but it was always a minor issue so long as the new left dominated gay politics, as it had since Stonewall,” he wrote. “In 1989, I laid out the conservative case for marriage equality, and argued that military service should join it as the top two goals of the gay rights movement. The left, from the grassroots to HRC to NGLTF, strongly opposed this set of priorities. It was derided as heterosexist, patriarchal, reactionary and oppressive.”

The community has a long history of pressing for marriage, though it was not at the forefront of the agenda until three same-sex couples sued in Hawaii state court in 1991 to win the right to marry there. Lambda Legal, the LGBT rights law firm, and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) eventually supported that suit. That advocacy was led by the left.

Founded in 1968, the member churches of the Metropolitan Community Churches have been marrying gay and lesbian couples since then.

The first court case brought by a gay couple seeking to marry came in 1971 in Minnesota. In 1979, a binational gay couple pointed to their 1975 Colorado marriage, which had been invalidated by that state’s attorney general, when unsuccessfully applying for permanent immigrant status for one partner.

In the nation’s capital in 1975, a city councilman introduced legislation to streamline marriage and divorce proceedings there. The bill defined marriage as between “two persons,” and gay activists seized on this language, saying it allowed same-sex couples to wed. Gay activists testified in favor of the bill.

“That came out of left field,” said Richard Maulsby, president of the Gertrude Stein Democratic Club, a gay political group, in a 1978 Washington Post article about the DC legislation. “No one expected it. No one had been pushing for it.”

The Unitarian Universalist Association, a denomination often associated with liberal causes, “became the first major denomination to affirm religious celebrations of the union of gay or lesbian couples,” the denomination said in a press statement in 1984.

In 1986, the ACLU adopted a policy to overturn “all laws that make homosexual and lesbian marriages illegal,” according to a 1986 United Press International story.

The next year, approximately 2,000 same-sex couples married in a mass wedding on the steps of the Internal Revenue Service in Washington, DC. The ceremony was meant to show the tax benefits for married people that are denied to lesbian and gay couples.

In March of 1989, the Associated Press reported that the Bar Association of San Francisco proposed model legal language that defined marriage as a “personal relation arising out of a civil contract between two people.” The language was seen as allowing gay and lesbian couples to wed.

Sullivan published his article, “Here Comes the Groom: A Conservative Case for Gay Marriage,” in the New Republic in August of 1989. In Sullivan’s recounting, community support for marriage followed his article.

“HRC wouldn’t even use the m-word until the new millennium,” he wrote. “The Clinton administration hated it. As did the gay press. The issue took off after Hawaii in 1993. But even then it was a struggle to be heard above those on the left arguing for employment protection, hate crimes, and economic ‘justice’ as core priorities… Without the emergence of the gay right, I don’t think we would have come as far as we have.”