A World AIDS Day event featured some skepticism about central components of the Plan to End AIDS, which aims to reduce the number of new HIV infections in New York State from the current roughly 3,000 a year to 750 annually by 2020.

“The thing that concerns me most is the issue of adherence,” said Dr. Mary Bassett, the city’s health commissioner, referring to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which involves the use of anti-HIV drugs by HIV-negative people to keep them uninfected.

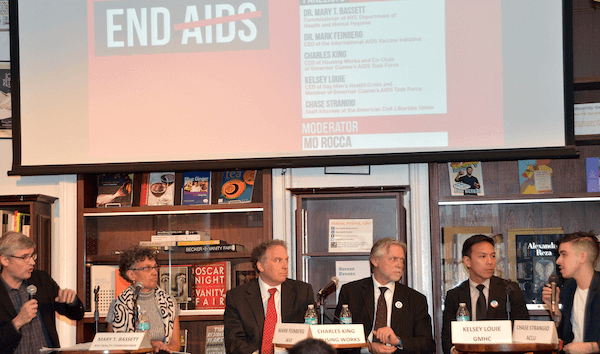

Bassett’s comments came at a December 1 event held at the Housing Works Bookstore Café on Crosby Street in Manhattan. Notably, she was joined on the panel by Charles King, the chief executive of Housing Works, an AIDS group, who is credited with developing the plan along with Mark Harrington, the executive director of the Treatment Action Group (TAG). King has been the plan’s leading champion.

City health commissioner, leading vaccine advocates voice questions whether PrEP is enough

While the plan relies on providing a range of services to HIV-positive and HIV-negative people, at its core, it uses anti-HIV drugs to cut new HIV infections. Along with PrEP, the plan relies on post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), anti-HIV drugs used by people with a recent exposure to the virus to keep them uninfected, and treatment as prevention (TasP), which treats HIV-positive people with anti-HIV drugs so they are no longer infectious.

All three drug regimens are highly effective when taken correctly, and the science says the plan should work. But it is a very ambitious plan and the first of its kind. While various types of prophylaxis that pre-date PrEP and PEP have been used before, Gay City News could not find a single example of any form of prophylaxis being used on the scale envisioned in the Plan to End AIDS. Only one infectious disease, smallpox, has been eradicated and that was done with a vaccine. Vaccines and cures have significantly reduced the incidence of other infectious diseases. TasP has worked well against some infections, such as tuberculosis, in some places.

Bassett’s concerns about PrEP adherence, concerns she has expressed since becoming health commissioner in early 2014, also have some basis in science. In early PrEP studies, adherence was a problem, with any new HIV infections coming among those who did not take Truvada, the only drug approved for PrEP, correctly.

More recently, a study of 200 gay men aged 18 to 22 in 12 US cities found poor PrEP adherence among the African-American men, who accounted for 53 percent of the participants. The amount of Truvada detected in their blood never rose above the level indicating they were taking the pill at least four days a week, which is the minimum dose required to obtain the anti-HIV protection.

“Our Black/ African-American youth were consistently below four-plus pills per week for the entire study,” Sybil Hosek, the study’s lead author and a psychologist at the Cook County Health and Hospitals System in Chicago, said at a July press event held at an International AIDS Society meeting.

The study followed the men for 48 weeks and reported four seroconversions during that time, for an incidence rate of 3.29 percent, which is high. The white and Latino men in the study consistently had Truvada levels in their blood that showed they were taking four or more pills a week.

The state’s epidemic is driven by new HIV diagnoses in New York City. The rate of new HIV infections among city gay and bisexual men has remained high and unchanged for years.

In 2014, there were 2,718 new HIV diagnoses in the city and 81 percent, or 2,194, were in men. Among men, 74 percent of the new HIV diagnoses were in gay and bisexual men. African-American men accounted for 39 percent, or 847, of the diagnoses among men, Latino men accounted for 34 percent of the diagnoses, or 743, and white men accounted for 21 percent of the diagnoses, or 467. So the population that New York must reach with a PrEP message — African-American gay and bisexual men — to get to 750 new HIV infections by 2020 is the population that right now looks like the one that is most likely to have adherence problems.

Bassett was not alone in expressing some skepticism about the plan. Dr. Mark Feinberg, the chief executive at the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, said that the AIDS epidemic could not be ended without a vaccine.

“I honestly don’t know when or if we will have a vaccine,” Feinberg said. “We’ve never made a vaccine against an infection like HIV before.”

King responded quickly.

“I want to disagree with my friend who I just met,” he said. “We don’t have a cure, we don’t have a vaccine, but we can end AIDS as an epidemic.”

Feinberg said later that places like New York and San Francisco might see success in ending their epidemics using prophylaxis and treatment. Those cities have the money and infrastructure that could make that success possible.

“PrEP can be highly effective if people take it correctly,” he said. “Unfortunately, that’s not the reality around the world.”