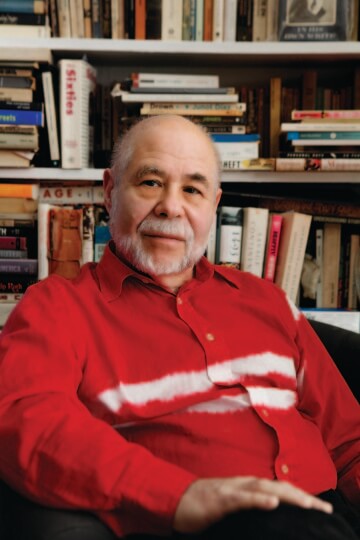

BY DAVID EHRENSTEIN | I’ve been thinking a lot about death lately. Hardly surprising as I turned 70 this past February. But my health is good and my spirits high, so I’ve probably got a reasonable amount of time ahead of me before the End Credits roll.

But that hasn’t stopped me from thinking about death and its consequences, as I have in earnest ever since the AIDS epidemic violently snatched away so many of my nearest and dearest — turning the 1980s and ‘90s into one long string of funerals, prefaced by hospital visits where “putting on a brave face” was the all-important shade of virtual make-up required. And in this, I am joined by an entire generation of gay men and those who loved us.

Marcel Proust felt the same way about World War I and the deaths it produced, noting to a friend, “In the terrible days we are going through, you have other things to do besides writing letters and bothering with my petty interests, which I assure you seem wholly unimportant when I think that millions of men are going to be massacred in a War of the Worlds comparable with that of Wells, because the emperor of Austria thinks it advantageous to have an outlet onto the Black Sea.”

PERSPECTIVE: LA Diary

Yes, for Proust World War I was like science fiction — and like AIDS, it decimated a generation This, in turn, evokes the query about how “real” death may seem to us in any context or circumstance whatsoever thanks to the AIDS pandemic.

Prior to AIDS’ cascade of horror, death had been an intermittent interloper in my life. It was initially associated with the elderly — persons whose “time had come.” That meant it was at such a distance from pre-adolescent me I needn’t think about it. Of course I thought about it in 1964 when my father died, and again n 1987 when my mother expired. But in both instances I was prepared for it, and this knowledge of death’s imminence cushioned the blow. A nominal “fear’ of Death had never become an “obsession” for me because for the most part it was kind of a sudden “disappearing act.”

I recall keenly when a little girl of my acquaintance who was my very age was struck and killed by a car crossing a street not far from my home. It was so passing strange I didn’t “take it personally.” I felt a bit differently about the death of “Kukla, Fran and Ollie” producer Beulah Zachary (immortalized by the show’s creator Burr Tillstrom as the puppet “Beulah the Witch”). She died in the crash of a commercial airliner, which plunged into the East River on approach to LaGuardia. Too close to home for comfort.

Woody Allen, of course, felt otherwise about death, declaring his terror of it from an early age and saying in adulthood that while knowing he would eventually face it he “just didn’t want to be around when it happened.”

This, in many ways, mirrors Andy Warhol’s pronouncement that death was “too abstract. I just say that they’ve ‘gone to Bloomingdale’s.’”

Needless to say Bloomingdale’s was filling up fast for Andy as so many of those he knew and loved had gone there — some through suicide, like dancer Freddie Herko and actress Andrea Feldman, others from what might be called “slow motion suicide,” like Edie Sedgwick.

AIDS picked up the pace considerably. You might say HIV made death more “abstract” for Andy than ever, as silence descended over the usually voluble pop artist whenever the subject arose.

Perhaps Andy felt he’d “said all he had to say” about death in his paintings — what he called his “Fashion and Disaster series” — canvasses devoted to car crashes, the electric chair, and dead celebrities like Marilyn Monroe and James Dean. The death of the latter in a car crash holds a special place in American pop mythology as he was quite young (24 is ‘before his time,” indeed), just on the verge of what would have been a spectacular career, and gay. But gayness was whispered about both in Dean’s day and Andy’s. He was gayer than IKEA on Superbowl Sunday, yet so strong was the social prohibition against talking about being in any “polite” conversational context, no one dared mention it. That’s not the case anymore, and the “wake-up call” of AIDS has a lot to do with it.

For me that “call” first came surreptitiously in 1979. I was in San Francisco visiting my friend filmmaker Warren Sonbert. A friend of his came to his house unexpectedly — rail-thin, completely bald, and emotionally at loose ends. He was returning an opera recording he had borrowed from Warren. Yet his manner indicated something truly operatic was bubbling inside him. When he left, Warren said his friend was apparently dying of “some sort of cancer” whose origin his doctors knew nothing about. Worse still they had no way to treat him. That night Warren and I went to see “Alien,” which had opened theatrically that day. The image of an interstellar monster planting its progeny in the body of a human that was then split open in order to give it “birth” became a central horror movie image. It was also, for me, an image of what AIDS would do to so many people in the years to come — Warren among them.

Hibiscus from the Cockettes theatrical troupe was an early AIDS casualty, and the first “big name” I came across to succumb. Rock Hudson was the “name” that far more people knew. But for me there was also countertenor Klaus Nomi, philosopher Michel Foucault, photographer Peter Hujar, playwright Charles Ludlam, to name but a few. AIDS took its greatest toll on the personal level.

But it was on the personal level that AIDS took its toll for me. That meant Sonbert, gay activist Vito Russo (who had also become an AIDS activist because of the disease), filmmaker Marlon Riggs whose “Tongues Untied” spoke of what it meant to be black and gay as no one (not even James Baldwin) had ever done before, singer-songwriter Michael Callen, matchless queer artist/ filmmaker/ theatrical impresario Jack Smith (“Flaming Creatures”), and Derek Jarman, the British experimental filmmaker who explored gayness in a way never before ventured in such seminal works as “Caravaggio” (1986), “The Last of England” (1987), and Edward II (1991).

I accompanied Derek and his muse Tilda Swinton around LA when he came for a visit and, armed with his video camera, shot images that became part of “The Last of England.” So in a way I was “on the set” of that great piece of cinematic poetry. Derek’s determination to work despite the disease that was killing him was boundless.

His last film, “Blue” (1993), was made after he’d lost his sight. In place of images, he simply had a blue motion picture screen with snatches of dialogue, poetry, and music as accompaniment as he went not at all “gently” into that far from “good night.”

And then there were the funerals. Two were special favorites. Lance Loud’s 2002 memorial service was held in the garden of Los Angeles’ Chateau Marmont and, in addition to the family of this famous gay “reality television” pioneer and rock singer, sundry luminaries including Van Dyke Parks, China Cammell, Danny Fields, and Chi Chi LaRue were assembled for the send-off — none knowing the first thing about the other.

Half a dozen years earlier, Advocate editor and gay man about LA Richard Rouilard, facing his death from AIDS, had made the arrangements for his ashes to be spread at sea. “Just drop me off in the Bu,” he’d said. “Somewhere off the coast of David Geffen and Sandy Gallin.” We did so in a boat ride whose soundtrack was “Judy Garland at Carnegie Hall” and Maria Callas intoning Richard’s favorite aria “Ebben? Ne andro lontana” from “La Wally.”

Many have noted that at the height of the epidemic funerals became great places to cruise. Poor taste perchance? Well life goes on after all. And circa 1995, after the development of several drugs to aid those who had seroconverted it went on at a new level.

But death goes on, too. And will continue to do so as long as we live — and long after it. W.H Auden put it perfectly:

“He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last forever: I was wrong. The stars are not wanted now; put out every one,

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun,

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good.”

Those are the last lines of his “Funeral Blues,” a poem made incredibly popular thanks to the 1994 British comedy “Four Weddings and a Funeral” –– the funeral being that of one of the film’s principal gay character, played by the out gay Simon Callow. His character died of a sudden heart attack, not AIDS. But being a 1994 release, “Four Weddings” arrived right on time for a great number of funerals, and the image of good cheer amidst sadness was much appreciated then. It still is.

And that in turn leads to my favorite mot juste uttered many years ago by noted LA wit Eve Babitz: “Death is the last word in other people having fun without you.”

I like to think of it that way. It sure beats “Bloomingdale’s.”