At a 2004 symposium titled “Catholics and the Death Penalty: Lawyers, Jurors & Judges” held at Fordham University, Charles Hynes, then Brooklyn’s district attorney and a professed opponent of the death penalty, cited three cases when explaining why he sought to kill 11 people under New York’s now-defunct death penalty law. For the district attorney, Darrel Harris, Jerry Bonton, and Michael Shane Hale stood out as murderers who deserved death because they “did not consider for a moment the mercy asked and pleaded for by the victims.”

Later in the symposium, Hynes, a devout Catholic, singled out Hale, now 48 and a gay man who has lived more than half of his life in prison, for harsh comments when discussing the role that mercy should have in the criminal justice system.

“But I have no mercy for someone who kills the way Michael Shane Hale killed,” said Hynes who died in 2019. “I think he should be locked up in a hole for the rest of his life. I think he should be held without any communication with any other human being for ending the life of another person, that his life should be over. So I can find no mercy for those kind of people.”

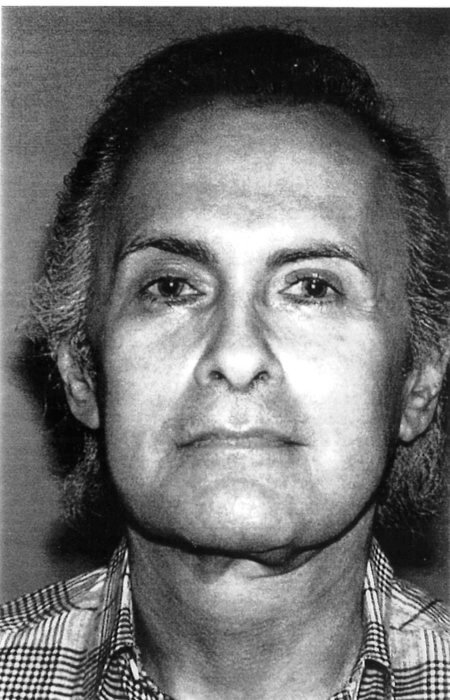

Michael Shane Hale, a gay man who killed another, at 23 not eligible for parole until he turns 73

New York’s most recent experience with the death penalty lasted from 1995, when then Governor George Pataki signed a death penalty statute into law, to 2004 when the Court of Appeals, the state’s highest bench, effectively struck down the statute. Pataki, a Republican who was governor from 1995 through 2006, promised to reinstate the death penalty in New York during his first campaign in 1994.

Over nine years, prosecutors in every county weighed bringing death penalty cases in 864 homicides, but filed death notices with state courts and the Capital Defender Office (CDO), the agency created by the death penalty law to represent death-eligible defendants, just 57 times. Pataki, who did not respond to an email seeking comment, applied pressure on prosecutors in 1996 when he removed Robert Johnson, then the Bronx district attorney, from the prosecution of Angel Diaz who was accused of killing Kevin Gillespie, a police officer, because he found Johnson insufficiently zealous in pursuing the death penalty. Diaz committed suicide in jail and was never prosecuted.

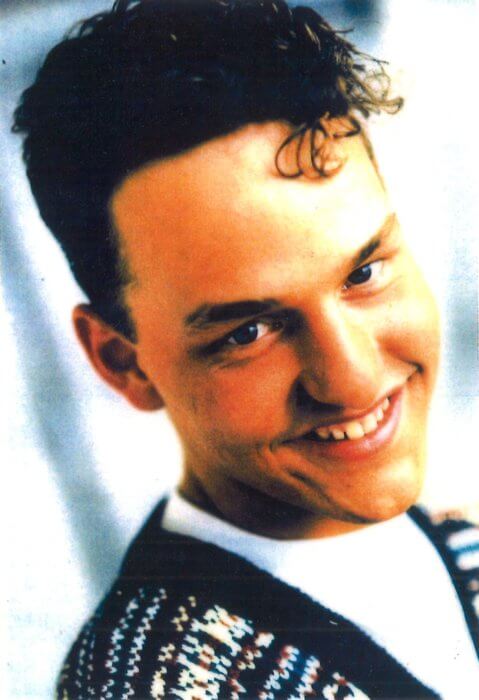

Hale was arrested in 1995 for the murder of Stefen Tanner, a 62-year-old man. Hale, then 23, had an on-again, off-again relationship with Tanner beginning in 1992. After graduating from high school in rural Kentucky in 1990, Hale held a few jobs, but eventually left for New York City where he could be openly gay. In Kentucky, he endured “prejudice, isolation, and emotional cruelty based on his sexual orientation,” according to a 1999 document prepared by the CDO. Showing his desire to flee that state, Hale pawned a necklace to buy gas for his car on his trip to the city, he said during a recent two-hour interview in Sing Sing prison where he is currently incarcerated. After surgery forced Hale to leave a job in the city, Hale turned to hustling to earn money. A client gave his number to Tanner, who contacted Hale.

“He ended up calling me later,” Hale said. “He ended up taking me out to dinner.”

That began a fraught relationship. Hale described Tanner as appreciative and abusive, forthright and manipulative, but mostly controlling. After Hale returned to work, Tanner required that Hale sign over his paychecks to him and dictated how Hale dressed, he said. Hale ended the relationship in 1993 and returned to Kentucky.

Tanner pursued the younger man. The 1999 CDO document notes that Tanner made “numerous calls” to Hale, including “more than sixty during one five-month period.” In September of 1995, Hale returned to New York City and Tanner.

On October 14, 1995, the two men had an argument in Tanner’s Sheepshead Bay apartment that was “loud enough for the neighbors to hear,” a detective in the NYPD’s Missing Persons Squad told LGNY, now Gay City News, in a 1996 interview. In court filings and other records, police and the district attorney’s office characterized the dispute between Hale and Tanner as “violent” — though it was never clear if they were referring to what happened in the apartment, the second fight that occurred later in the apartment building’s parking garage, or both.

In the apartment, Tanner called 911 and told the operator he was being robbed by a white male with a knife. When police arrived, they found no robbery and no knife. It was a “clothes job,” or a task in which they are required to supervise the distribution of possessions between roommates or friends who are ending their relationship, according to 911 records. Police rules required them to treat the dispute as a domestic violence incident. From their arrival in the apartment to escorting Hale out of the building with some of his possessions and $500 Tanner gave him, the two officers were on the scene for 28 minutes.

Hale said that Tanner had previously been violent “a couple of times like a knock on the head,” and on that morning Tanner hit him on the head with a phone. Hale wanted an end to the relationship and he wanted all of his possessions returned to him, he said. After being escorted out of the apartment, he reentered the building through the parking garage and waited by Tanner’s car.

“The single thing that I wanted was to end the relationship was to get my things and just leave and never have to deal with this again,” he said during the Sing Sing interview. “The thing he told me that made me think this is never going to end was, ‘I want you to go to your Mom’s and then we’ll discuss it.’”

After the police left, Tanner called his niece at his Brooklyn store and told her he would be late. He had the locks on his apartment changed and then went to the garage where he encountered Hale. They fought again with Hale knocking the older man down and hitting his head on the cement floor twice. Tanner was still alive, but bleeding when Hale put him in the trunk of Tanner’s car. He drove the car around Brooklyn for a time. When he heard Tanner yelling his name and hitting the trunk of the car, Hale opened the trunk and placed a plastic bag over Tanner’s head. Hale eventually drove the car, with Tanner still in the trunk, to Kentucky where he dismembered Tanner’s body and discarded the parts. Tanner’s body was never found.

Hale, who readily admits he is responsible for Tanner’s death, had no criminal record prior to killing Tanner. Incarcerated since 1995, he has earned an associate’s degree, a bachelor’s, and a master’s degree. He lives on an honor block in Sing Sing.

“I had no history of violence before this,” he said. “Growing up in prison, I’ve never once chosen violence as a way to deal with the stress, the anger… For me, it’s about maximizing the good that I can do with the time I have left.”

As his case proceeded through the Brooklyn courts, the first flaw in New York’s death penalty statute became apparent. Hale was the first person charged under the statute in New York City. When Hynes announced his decision, there were immediate protests from LGBTQ groups that believed that Hynes would rely on anti-gay stereotypes to win a conviction. In 1997, he began negotiating a plea deal for Hale with the CDO, but Albert Tomei, the judge in Hale’s case, said he was unable to accept a guilty plea because the plea provisions in the statute were unconstitutional.

Tomei, who died in 2017, found that only defendants who pleaded guilty avoided the death penalty. And only those who asserted their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination by not pleading and asserted their Sixth Amendment right to a trial faced a possible death sentence. That component of the statute was coercive and punished defendants who exercised their constitutional rights, Tomei said. In late 1998, the Court of Appeals agreed with Tomei and voided that part of the statute.

In 1999, Hale pleaded guilty to second-degree murder, kidnapping, and robbery for a sentence of 50 years-to-life. His earliest release date will be in 2045 when he will be 73 years old.

“I couldn’t understand some of the people who claim leadership who were suggesting that the decision was homophobic when the victim was also gay,” Hynes said in a 1998 LGNY interview. “[Hale] had an opportunity to save Stefen’s life and instead chose to suffocate him. The fact that I offered to accept a penalty other than execution should be a clear indication that where I am given an opportunity… I am going to be inclined to do it whether the defendant is gay, African-American, or Irish or Italian.”

In 2004, the Court of Appeals struck down the statute entirely after finding that the instructions the law required judges to deliver to juries were unconstitutional. Death cases had a guilt phase where jurors had to decide if the defendant was innocent or guilty. With a guilty verdict, jurors then had to decide between life without parole or death in the penalty phase. Judges had to tell jurors that if they could not unanimously find for one penalty then the judge would sentence the defendant to 20- or 25-to-life meaning the defendant would be eligible for parole after serving the minimum. That was “coercive,” the court found, and tended to influence jurors to choose death. It was up to the State Legislature to correct that flaw, the court said.

In contrast to the drafting of the original legislation, which occurred behind closed doors with no public comment, legislators held five public hearings on the death penalty in 2004 and 2005. They invited anyone to testify and ultimately heard from 146 witnesses. Few favored the death penalty, according to a 2008 article by James Acker, a law professor at the University of Albany, that was published in the Vermont Law Review.

“All these folks, years and years and years, pro death, pro death, pro death. Where are they?,” Acker quoted James Rogers, then the president of the Association of Legal Aid Attorneys, saying at the final hearing. “The truth of the matter is, is that when they have seen what we have all seen throughout the country, all the exonerated people on the evening news and the evidence in state after state and jurisdiction after jurisdiction, it’s hard to build up a head of steam in favor of the death penalty.”

Andrew Cuomo, who would go onto New York’s governor, said, “Sometimes, silence can be deafening” at one hearing, according to Acker.

Of the 57 people who were sentenced under the death penalty law during its short and contested life, seven were sentenced to death only to have those sentences changed to life without parole on appeal. Altogether, 44 of the 57 are serving life without parole. Eleven, including Hale, have sentences with a minimum, though two of those 11 have what are effectively life sentences. One will be 123 years old at his first parole hearing and the second will be 136 years old at his first parole hearing. Three of the 11 were sentenced to 25-to-life and will have their first parole hearings in 2022. One, Diaz, committed suicide in jail and never went to trial. The last was acquitted at trial. Four of the 57 died in prison.

In its application, the statute had the same biases that are commonly seen in criminal justice. Fifty percent of the death-noticed defendants, or 29, were Black; 21, or 35 percent, were white; and five, or eight percent, were Latino. One was an indigenous person and another was an Arab. In Brooklyn, nine were Black and two were white. These identities were gathered from CDO and state corrections records.

“It’s inevitably racist, no matter how hard we try,” Kevin Doyle, who headed the CDO, told Gay City News. “There will inevitably be wrongful prosecutions, but beyond that it adds an extra layer of pressure.”

Doyle, who is a devout Catholic, was the second speaker at the 2004 symposium held at Fordham University. For Doyle, these sentences foreclose the possibility of rehabilitation, which can be a good example for other inmates, and they suggest that these offenders, some of whom committed admittedly horrific crimes, cannot be redeemed.

“I think it’s important to express the religious value of redemption in the secular section of our penal system,” Doyle said. “[Aleksandr] Solzhenitsyn said the line between good and evil does not lie between nations or people, but in the human heart. It is important to reinforce that the line can move and people can find redemption.”

Kyle Reeves, who was an assistant district attorney in Hynes’ office for 25 years and left there in 2013, was the lead prosecutor in the Hale case. He now doubts that Hale was ever the “worst of the worst,” who would be targeted under the statute, as proponents of the law argued at the time.

“I wondered at the time if Michael Hale was the person this law was designed for and I’ve reached the conclusion that it wasn’t,” said Reeves who is now in private practice. “What he did was horrendous, but I don’t think it was any worse than any of the other 160 murders that I tried… He’s not the guy if you put him out on the street 25 years later… he’s not going to kill again.”

During the proceedings that led to his guilty plea, Hale, at times, just wanted to die. As the plea deal loomed, he understood that he would be in prison seeing people who committed the same crime he did leave prison after serving a 25-year minimum and winning parole. He now says, “I should be in prison for 25 years,” but what is called for is a second look at the cases prosecuted under New York’s failed death penalty experiment.

“For me, is there any possibility or way people can look in the lens of 2020… and look at people as a whole person,” Hale said. “I really wish they could go back and look at these cases.”

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.