Public officials in the city and state should suspend marijuana enforcement until Albany resolves the pressing question of legalization.

A new consensus is gaining momentum that the risks of marijuana can be controlled by public health measures. At its recent State Convention, New York State Democrats supported legal adult sales of recreational marijuana, declaring that weed is “is less harmful than alcohol and tobacco.”

Meanwhile, top health officials in New York City and New York State have endorsed a tax and regulate model for adult recreational use. It is a new era where health issues need no longer hinder legalization, and the debate centers on how to implement a new approach to marijuana.

In a report to Governor Andrew Cuomo made public last week (see related story on page 11), Dr. Howard Zucker, the state health commissioner, said he doesn’t subscribe to the theory that marijuana represents a gateway to harder drugs. Zucker’s conclusion has been widely held by other public health officials for years. The National Institute of Drug Abuse points to some rodent studies that indicate early use of marijuana could make the brain susceptible to an appetite for other drugs. Studies like this agree with epidemiological data that show that use of drugs in early adolescents is correlated with abuse as adults. But then there is a big qualifier here: “the majority of people who use marijuana do not go on to use other, ‘harder’ substances.”

Moreover, NIDA notes “cross-sensitization is not unique to marijuana. Alcohol and nicotine also prime the brain for a heightened response to other drugs.” This trio of drug are “typically used before a person progresses to other, more harmful substances.”

Given this pattern, NIDA offers “an alternative to the gateway-drug hypothesis.” Drug users “are simply more likely to start with readily available substances such as marijuana, tobacco, or alcohol, and their subsequent social interactions with others who use drugs increases their chances of trying other drugs.” You choose friends you are comfortable with and, in turn, you have shared activities.

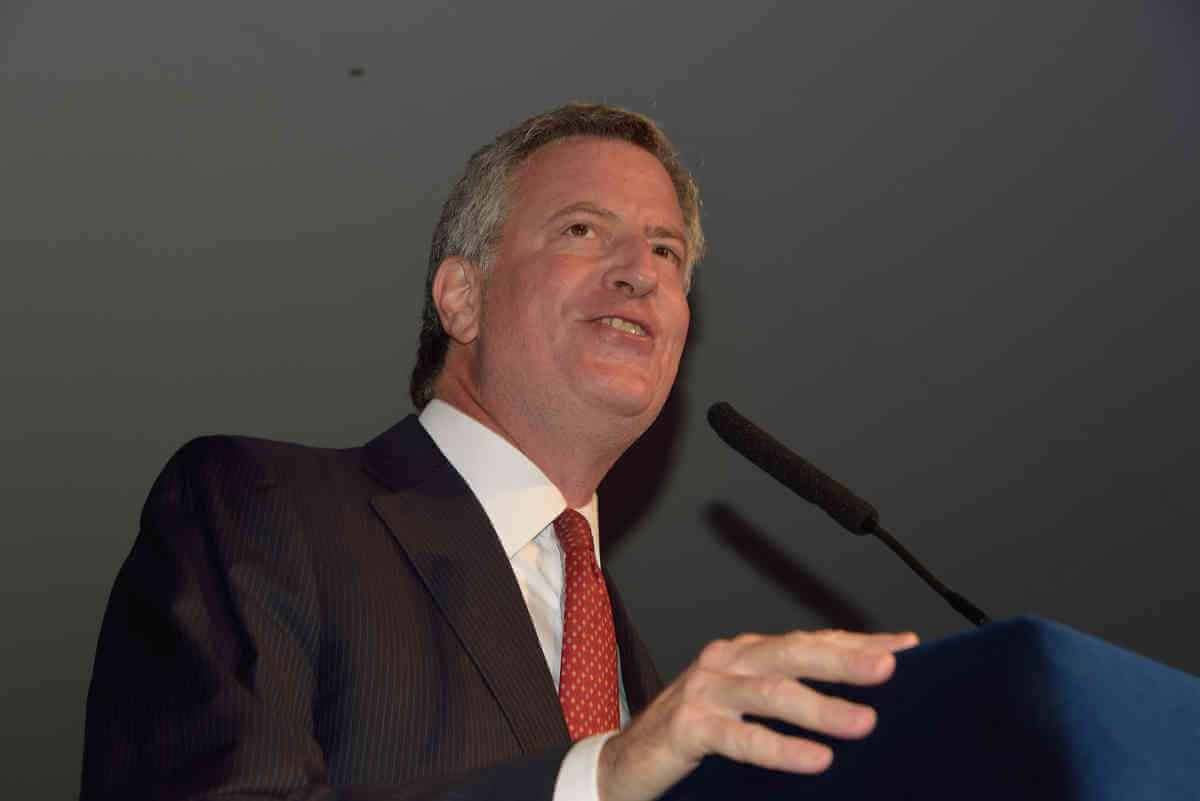

From this perspective, the longstanding war on pot is not justified; use of marijuana may have a link to other drug use later in life, but it doesn’t necessarily cause it. Arrests are unwarranted, particularly given the high likelihood that legalization is on its way, but Mayor Bill de Blasio remains stubbornly resistant to this new reality.

With a great flourish, he recently announced that smoking in public would be greeted with a summons not arrests, arguing he was making a real concession. But other member of the Democratic Party and advocates blasted his proposal.

The chairs of two criminal justice committees in the City Council joined advocates June 20 on the steps of City Hall attacking the mayor’s plan. Their critique burst de Blasio’s hopes of appearing progressive; the plan, they said, represented only the smallest of steps forward.

Queens Councilmember Rory Lancman, who heads up the Committee on the Justice System, blasted the mayor’s plan on the steps of City Hall and in a statement, saying, “No one should be arrested for smoking marijuana, period.” Calling the new plan a sham, he noted that a speeding ticket is a civil summons, but that de Blasio’s action on marijuana involves a criminal summons.

“The mayor’s policy does not attempt to reduce criminal summonses at all, still allows arrests in circumstances that cannot be justified by public safety,” Lancman said.

Then, in a thrust that must hurt a mayor whose political persona is defined by opposition to all forms of discrimination, Lancman predicted the plan “will likely make marijuana policing even more discriminatory toward people of color, continues to expose noncitizens to deportation, and takes no steps to eliminate the collateral consequences which are in the city’s control.”

Joining him was another Queens councilmember, Donovan Richards, who chairs the Committee on Public Safety that oversees the NYPD, as well as Brooklyn Councilmembers Antonio Reynoso and Jumaane Williams, the latter of whom is challenging Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul in the September Democratic primary and is aligned with Cynthia Nixon’s gubernatorial bid.

City Comptroller Scott Stringer, a likely candidate for mayor in 2021, joined the demonstrators, saying “too many live have been ruined, too many people of color have been targeted.” As he left the speaker’s podium, he reminded everyone that he is “the money guy. If you will legalize, you will actually create a $3 billion dollar industry” and tens of thousand new jobs. With more revenue, he said, “you will have an opportunity to invest more in the community.”

Kassandra Frederique, state director of the Drug Policy Alliance, called for a “clear-cut policy saying no arrests, no justification for putting people into the criminal system — period.”

Public defenders, organizations representing minority youth like Make the Road New York, and drug reformers like VOCAL-NY also stressed that New York must stop relying on criminal penalties.

Under the mayor’s plan, anybody stopped for marijuana who is not carrying identification can be arrested and fingerprinted and that could lead ICE to identify them for deportation, Legal Aid Society lawyers argued.

According to de Blasio, his plan will make things better because there will be fewer arrests.

But he avoids a basic ethical question. If marijuana will be legal in eight or nine months, how can enforcement be justified now? Campaigners for legal marijuana are eager to avoid any arrests for a drug that is less harmful than alcohol or tobacco. Keeping young people’s records clean means they can can qualify for better jobs and increase their earning potential — a factor particularly salient in low income neighborhoods and communities of color. This is one piece of the argument that legalization will be good for the state’s economy.

The case against arrests is implicit in the Democratic Party’s recent resolution. “Marijuana laws have not had a significant impact on marijuana availability,” the statement reads. If the law fails to curb use, then no individuals, much less poor black and brown youth, should be criminally punished in a futile exercise. That is why enforcement should be suspended and the Legislature be given time to create a new policy.

The mayor’s “advance,” meanwhile, continues major injustices. As Gothamist headlined its story about de Blasio’s announcement: “NYPD Will Stop Arresting SOME People For Smoking Pot.” Among those who will be arrested are parolees. It is hard to think of a crueler outcome for getting high than going back to prison after enjoying freedom. In fact, according to the Daily News, some federal judges are refusing to play along with this. Judge Jack Weinstein, a liberal lion on the federal bench in Brooklyn, made the news with “a remarkable 42-page ruling explaining why he would not send 22-year-old Tyran Trotter back to prison for three years — longer than his original sentence! — for smoking pot, a technical violation of his post-release terms,” according to the Daily News.”

In his years as mayor, de Blasio has displayed an uncanny talent for isolating himself politically. His ties to the drug reform movement were already frayed by his long delay in supporting safer consumption spaces that offer medical support to drug users during their time of greatest peril in the minutes after they inject. His months-long stall on the issue is now being followed by Cuomo’s own foot-dragging in giving the state’s go-ahead.

If de Blasio were to advocate for complete suspension of marijuana law enforcement pending action in Albany, he would become a leader with a national constituency and polish his fading progressive image. Instead, he is allied with the police, which will always show more loyalty to Cuomo than to him in any event. At a time when the mayor needs allies and a chance to reignite the initial enthusiasm he stirred, he is increasing his troubles by standing pat rather than making a bold move forward.