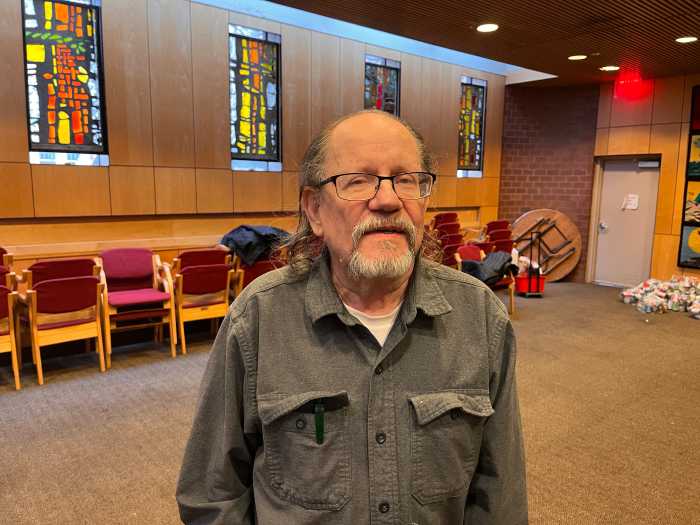

Throughout his career, David Rothenberg has been a passionate advocate for LGBTQ rights. At 91, he’s had a unique and deeply personal window into the ongoing struggles over the past six decades or more. Though he might blush at the description, he is a lion of the movement — a movement that he says is still going on today and, he says, has more urgency than any time in recent memory.

“I’ve lived forever,” he says, chuckling, in an interview with Gay City News, “but I’m particularly distressed at young people not knowing history, the lack of knowledge about our own movement, people who have done heroic things like Larry Kramer or Ginny [Virginia] Apuzzo who was extraordinarily important in the AIDS crisis, and we were all part of something that was really crucial.

He added: “It’s important to know your history, and we’re seeing now an attempt to remove history. We have to fight for our past because if you don’t know where you come from, you don’t know where you’re going.”

It would take volumes to chronicle Rothenberg’s amazing accomplishments. He’s had a diverse career, beginning as a Broadway press agent and evolving into a passionate activist because of a play.

When he was working on the play “Fortune and Men’s Eyes,” which premiered in 1967, he became aware of the horrors of life behind bars for many people — and gay people especially. At a talk-back after a performance, an audience member challenged the play as being unrealistic. Another audience member stood up and said he was an ex-prisoner, and the play was very realistic. Rothernberg called him down:

“His name was Pat McGarry, and he said, ‘not that my 20 years in the joints counts for anything…’ He talked about Riker’s Island and Stanmore Prison, the Florida chain gang, and San Quentin.”

From that initial meeting, Rothenberg, McGarry, and author Clarence Cooper, who had written “The Farm” about hellish life in a drug rehab, began to work together. Understanding how difficult life was for people released from prison, they founded what would become The Fortune Society, an organization designed to help with transitions from prison to the world. Started on a $32 stake from Rothenberg, with just five people working, today there is a staff of 600 people and an annual budget of $80 million.

It was during the early years of The Fortune Society that Rothenberg came out publicly on national TV.

“It was a big deal in 1973 that the head of a non-profit organization was coming out,” he said.

The David Suskind Show had previously covered the organization, but there were other issues stirring for Rothenberg:

“The Fortune Society was six years old. I’m working with men and women about their being honest with their lives. And I suddenly realized the duplicity in my life. And I called the same woman at David Suskin program and said, ‘Have you done a program about people living dual lives?’ They had done gay shows about activists, but what about those that have careers and fields that are not? And she said, ‘great program. Do you know anybody?’ And I said, ‘yeah, me.’”

“I pulled the key people at Fortune Society together who I’d been working with for six years, and I said, ‘I have three things to tell you. One is I’m gay. Two, I’m going on a national television show. And three. And I handed them a letter and I said, ‘this is my letter of resignation.’ There was a long pause, and [board member] Kenny Jackson said, ‘what are you gonna wear on television?’”

It was, however, a big deal, and the response was overwhelmingly positive. But, in typical style, the “New York Post” ran a headline: “Prison Exec Says I’m a Homo!”

During the AIDS crisis, Rothenberg was part of a group that convinced “The New York Times” to begin covering AIDS. During the early years of the crisis, the paper stayed away from coverage, and there were threats to picket the building.

“This was the major health crisis of the second half of the century,” Rothenberg said. “And the ‘Times’ had been in absentia.”

So, he and Apuzzo, along with Andy Humm, went to see publisher Abe Rosenthal. Rather than the conflict they were expecting, Rosenthal asked for their help.

“We were stunned,” Rothenberg said. “And I said, ‘you don’t need us. You could get the closeted gay people on your staff, and they can cover all the things that have to be done.’”

These are just two examples from a lifetime of service, and there is so much more to Rothenberg’s life. His work as a press agent threw him in the way of glamorous celebrities — which he notes is not always so glamorous. He spent time escorting Elizabeth Taylor through Toronto in the early days of her relationship with Richard Burton while he was doing “Hamlet,” and became a lifelong friend.

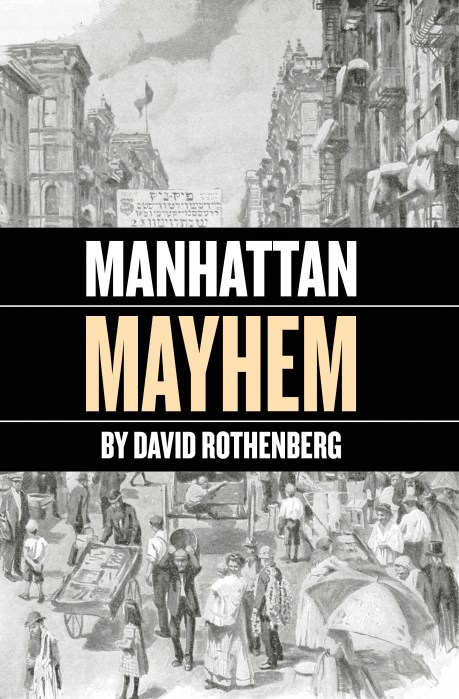

Rothenberg is also a keen observer of life, and at 91 he has just published his latest book, “Manhattan Mayhem,” a series of stories in a thinly veiled memoir about his family, his life, and the fascinating people he’s met along the way.

What comes through in these tales — as in all of his biography — is a man who is committed to helping and supporting those in need and to living in his own truth. And he’s nowhere near done.