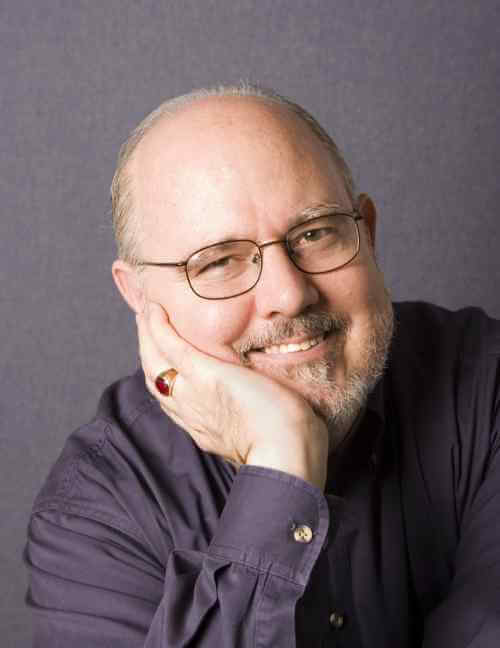

In a moving memorial celebration held at the Stonewall Inn on April 15, David Carter — the activist, historian, and writer who authored the definitive history of the civil disobedience that erupted in response to a police raid on the historic gay bar in late June 1969 — was remembered by family, friends, and colleagues as a fierce defender of the LGBTQ community who, more than anything else, was always a “gentleman.”

In a lifetime of activism, Carter will be best remembered for his acclaimed 2004 book “Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution.” He died in his West Village home on May 1, 2020 at the age of 67, while still conducting research for a planned biography of Frank Kameny, the Washington-based Mattachine Society leader whose gay activism pre-dated Stonewall by nearly a decade.

William Carter, David’s only sibling, who was 11 years his senior, opened the April 15 memorial by saying he intended it to celebrate “a legacy based on love and a sense of justice and dignity for everyone.”

William, a renowned Proust scholar, lives in Georgia, and the COVID crisis and recent health issues in his family meant that David’s memorial came just weeks before the third anniversary of his death.

William recalled meeting up with his brother in France in the early 1970s when a 21-year-old David came out to him. William was open to the news, but worried about his brother’s life being difficult.

But David, he said, “devoted his life to make the lives of others less difficult.”

Scott Seyforth, a founder of the Madison LGBTQ Archive, recalled meeting Carter there when David was a graduate student in South Asian Studies at the University of Wisconsin. Madison became a focal point in an explosive gay rights battle that followed singer Anita Bryant’s successful 1977 campaign to repeal a nondiscrimination ordinance in Dade County, Florida. Similar repeal efforts were quickly approved in St. Paul, Minnesota, Wichita, Kansas, and Eugene, Oregon, but Wisconsin’s capital city was the first in the nation to beat back the anti-gay backlash.

“David was central to the movement in Madison,” Seyforth said, noting that Carter also played a lead role in Wisconsin enacting the nation’s first statewide gay and lesbian nondiscrimination statute in 1982.

Carter also took advantage of cable TV community access to create a weekly, Sunday evening prime time program “Glad to Be Gay.” Seyforth recalled Carter grilling the Madison police chief and Dane County district attorney about police violence against the LGBTQ community. After interviewing the famed countercultural poet Allen Ginsberg, the two became friends. In 2001, four years after Ginsberg’s death, Carter published “Spontaneous Mind,” a collection of interviews the poet had given dating back to the 1950s.

Seyforth noted that Carter’s research on Stonewall — including audio tapes of roughly 145 interviews with riot participants and witnesses, as well as the police inspector who led the June 1969 raid — and his background work for the Kameny biography are archived at the University of Wisconsin.

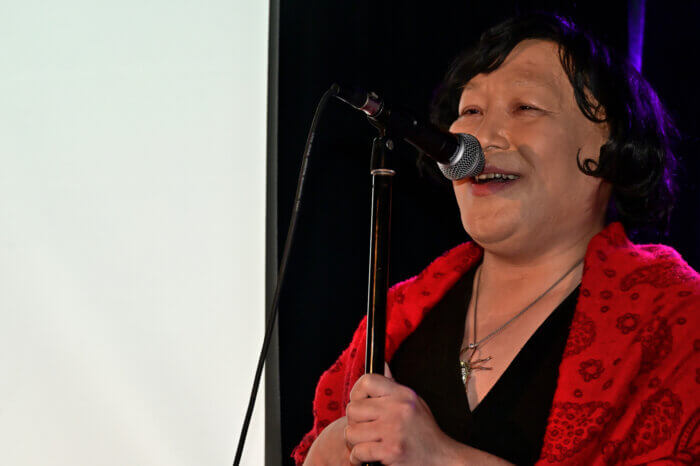

Pauline Park, a longtime transgender rights activist in New York, said she also met Carter in Madison while she was an undergraduate there. She recalled their two-year relationship, which included traveling to Washington in 1979 for the first gay and lesbian march on the nation’s capital. Years later, the two picked up their friendship in New York, and Park assisted Carter in transcribing some of his audio interviews for the Stonewall book.

Ken Lustbader, an historic preservation professional who co-founded the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, spoke about the pivotal role Carter played in first getting the Stonewall Inn designated a National Historic Landmark and later winning approval from the National Park Service, during Barack Obama’s presidency, for the Stonewall National Monument in Christopher Park, across the street from the bar.

“He was our gentle talking head,” Lustbader said, explaining that Carter’s granular mastery of the details surrounding the several days of riots and his gracious patience gave federal officials the confidence to move forward.

Activist Andy Humm, a Gay City News contributor who co-anchors the cable news program “Gay USA,” said that part of Carter’s mastery of what happened in June 1969 came from smoking out the phonies. He recalled Carter saying that when he was suspicious of someone’s claim to have been at the Stonewall riots, he would describe a false scenario and ask them if they recalled that. Those who said they did confirmed his suspicions.

Mark Segal, the publisher of Philadelphia Gay News who was 18 when he participated in the Stonewall riots, acknowledged that his first encounter with Carter was anything but gentle. Disagreeing with parts of what he read in Carter’s Stonewall book, Segal, “furious,” phoned him. In the face of Carter’s calm, patient responses, Segal hung up on him.

But years later, as Segal was working on his 2015 memoir, “And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality,” Carter contacted him to offer advice and assistance on his research.

“We became friends, and started doing panels and talks together,” Segal said. “David was a gentleman.”

Scott Bramlett, a friend of Carter’s, played an informal role in David’s historical work. The two would meet in different locales around Manhattan, and on occasion Carter read him portions of his draft chapters on Stonewall.

“He was so self-effacing,” Bramlett said of Carter’s modesty about his ground-breaking work. “David had a heart full of love.”