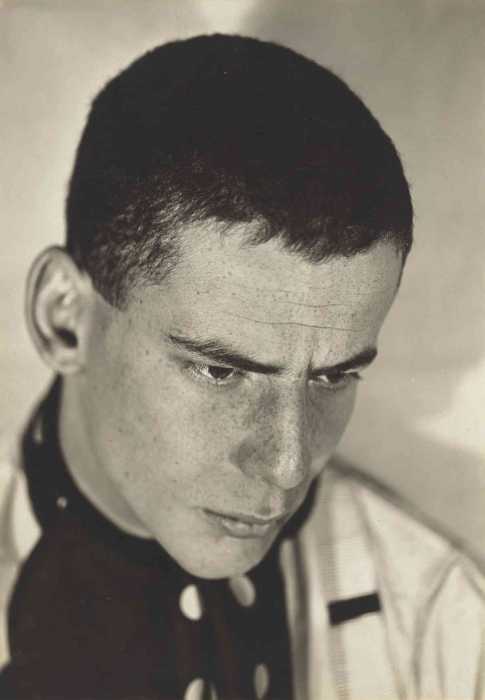

Dance Theatre of Harlem's Da'Von Doane. | RACHEL NEVILLE

The premise that Arthur Mitchell –– the first African-American dancer in George Balanchine’s New York City Ballet Company –– strove to establish was that black dancers can do classical ballet as well as white ones. He founded a ballet school in Harlem and shortly thereafter a company, Dance Theatre of Harlem, to prove it.

New York ballet companies remain overwhelmingly white with a smattering of Asian and Latin dancers, but blacks have long since proven their mettle in companies across the land and around the world. Still, racial integration in the major companies is token at best.

Now under the artistic direction of Virginia Johnson, Mitchell’s muse and long-time prima ballerina, DTH returns to New York after a nine-year hiatus with four performances at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater through April 14 (ironically the same dates as an all-too-rare appearance of Netherlands Dance Theatre at the Koch Theater up the street). Dance Theatre of Harlem’s opening night program included Balanchine’s “Agon,” Petipa’s “Swan Lake, Act III Pas de Deux” (the Black Swan), and contemporary works by John Alleyne (“Far But Close”) and DTH’s resident choreographer Robert Garland (“Return.”)

The good news is that the company looks beautiful and is dancing like a world-class ballet troupe. The better news is that its rendition of Balanchine’s “Agon” –– in which Mitchell, DTH’s artistic director emeritus, starred in 1957 with New York City Ballet –– is, as staged by Richard Tanner, technically as clean as a whistle and performed with just enough jauntiness to give its formal abstraction flavor.

After introducing the iconic motifs in the opening single, double, and triple Pas de Quatres (four men; eight women; and eight women and four men), come two Pas de Trois (the first with a man and two women; the second with two men and a woman) and a Pas de Deux, before a finale of duets and trios for the whole cast.

The dynamic crackle of this expert group revitalizes Balanchine’s choreography. The men toss their back legs into arabesque with force enough to rock their standing foot back on its heel. The women thrust their pelvises forward and drop into perilously wide second position plies, sending them virtually onto the fronts of their toe shoes. In DTH’s dancers, these signature distortions of classical ballet line seem as shockingly innovative as they were in the 1950s and '60s, when Mr. B introduced them.

Standouts on opening night were lithe Taurean Green, the male in the first Pas de Trois, willowy Chyrstyn Fentroy, the woman in the second, and Gabrielle Salvatto with Fredrick Davis in the Pas de Deux, which ends in a passionate embrace that in 1957, with a black man and white woman, represented Balanchine’s defiance of America’s racial status quo.

The purely classical offering of the evening, the Black Swan Grand Pas de Deux, received a stirring, in-your-face performance by tiny spitfire Michaela DePrince and her gallant prince, Samuel Wilson. The dramatic byplay of the counterfeit Swan teasing then spurning her puzzled prince made their characters’ intentions crystal clear, even outside the context of the full ballet. In the virtuosic highlight, the legendary 32 fouette turns, the fact that DePrince inserted double pirouettes with flapping wings between the first eight virtually erased her drift toward the right during the last 16. That mattered only to purists, if at all. The couple’s verve and her connection with both her partner and the audience –– coupled with technical assuredness –– had already won us over completely.

John Alleyne’s “Far But Close,” with live string and piano music by Daniel Bernard Roumain and poetry by Daniel Beaty, was developed last year in a residency on Martha’s Vineyard. With musicians onstage, barely visible behind a scrim, two couples –– an Apollonian one (Stephanie Rae Williams and Jehbreal Jackson) and a Dionysian one (Ashley Murphy and Da’Von Doane) –– dance a discourse of love versus sex.

The overwrought text implies that sex is okay, but not so love’s entanglement for the “pretty little black girl,” Murphy, and her muscular swain, Doane, who pursue their passions in fragmented duets that offer some striking partnering work. The other couple, Williams and Jackson, comment on the raw sensuality of the first couple with a cooler attitude. The ballet is too long by half, since it gives us no new emotional information in the last third and its extended final duet for Murphy and Doane becomes generic and repetitive.

Trimmed and focused, “Far But Close” might gain more emotional depth and become a substantive part of the DTH repertory. It was the evening’s only piece that was not either abstract (“Agon”), virtuosic (“Swan Lake”), or superficial, like the feel-good closer, Robert Garland’s 1999 “Return,” a five-part suite set to music by James Brown and Aretha Franklin. Soulful, yes, but geared purely for entertainment.

The dancers clearly have a ball doing “Return,” strutting and shaking their booties in toe shoes to the funky Brown classics. Murphy and Doane are featured in the opening “Mother Popcorn,” and when they cut loose, they’re dynamite. Murphy’s musicality shines, as she plays with hitting the accents head on and knowing when to finesse them for added impact. Doane is a dynamic powerhouse with a seductive, in-your-face presence.

The program earned a well-deserved standing ovation for the company’s commitment, passion, and skill. If audience enthusiasm were gold, DTH’s future would be secure. Now what? If it chose to, DTH could make itself unique in a crowded ballet market by serving as a vehicle for developing and showcasing new contemporary ballet choreographers –– black, white, and of every hue.

DANCE THEATRE OF HARLEM | Jazz at Lincoln Center, Rose Theater| Broadway at 60th St. | Apr. 12-13 at 8 p.m.; Apr. 13 at 2 p.m.; Apr. 14 at 3 p.m. | $25-$125 at jalc.org