This month, the exuberantly out countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo finished up a busy curating/performing turn as artist-in-residence at the New York Philharmonic. After reprising his duo cabaret appearances with Mx. Justin Vivian Bond (a program now available as a Decca release) he appeared with the Phil under Music Director Jaap van Zweden in Alice Tully Hall February 5, the second of two concerts under the rubric “Authentic Selves: The Beauty Within.”

The invigorating evening started off with Beethoven’s Leonore Overture #3 — not in any sense a concert rarity, but always welcome and presumably included since the titular heroine operates in drag (as “Fidelio”) to obtain her unjustly imprisoned husband’s release. Next, Costanzo entered (to an enthusiastic welcome) to traverse Hector Berlioz’s song cycle “Nuits d’été,” to poems by Théophile Gautier. It’s hard to believe, but this work — which now figures as a key vocal/orchestral work up there with Mahler’s “Das Lied von der Erde” and Strauss’ “Four Last Songs” for many concertgoers and recording collectors — only gained real currency in the 1950s and ’60s. As it happens, all three works deal with loss.

The Berlioz songs were originally written for piano accompaniment and with four different voice types specified. Berlioz orchestrated them at different times and led performances involving single songs — or, if more, with a male and female soloist both. It’s only since the pioneering late 20th century recordings that the tradition of a mezzo or soprano taking on all six has become fairly standard. Leading countertenors, including David Daniels and Philippe Jaroussky, have sung them before, but not often the full set in live performance. Costanzo overcame the challenges of the set with remarkable artistry and musical and verbal expressiveness, though not always full vocal ease.

Within his comfortable range — which included dramatic dips into his baritone range, a must in the openly tragic “Sur les lagunes” — Costanzo provided many beautifully limned phrases and exquisite soft dynamics. As an interpreter, he also captured through stance and inflection the texts’ shifting personae of lovers addressing their (here female) love objects, lost and found. His sensibility especially served the achingly beautiful “Le spectre de la rose” — which for many has resonance from Laurie Lind’s 1991 short “RSVP,” one of the New Queer Cinema’s landmark films about AIDS. But he also found the charm and specificity for the final “Île inconnue,” in which we (finally) hear a woman’s voice alongside that of her insouciant suitor. “Nuits d’été” may not prove central to Costanzo’s vast repertory, but it was well worth hearing him perform it.

New York-based Gregory Spears’ ever-growing body of work has often treated on aspects of queer life, notably in his masterful operas “Paul’s Case” (2009, based on a Willa Cather story) and 2016’s deeply affecting “Fellow Travelers,” a treatment of Thomas Mallon’s novel about the McCarthyite “Pink Scare.” Written for Costanzo to première, Spears’ new song cycle deploys a brilliant formal twist: its four component songs utilize different musical procedures and the instrumentation and style of orchestration vary. The text, however, remains the same: Emerita US Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith’s poem “Love Story,” which deal with a lost love and his all-too-present absence. (To ponder: does a gay male composer setting a straight woman’s verse for a gay male singer perforce constitute “queering the text”?) There are no pauses between the component sections, and the fourth recapitulates musical and instrumental gestures from the preceding three. This lends the quarter hour work the sense of a lover obsessively ruminating about his departed beloved, with different emphases and emotions.

The instrumental writing is deft and compelling on its own terms, moving from post-Debussy haziness to an almost Korngold-like brass-fueled tonality in version three. As Spears and Costanzo have collaborated before, the instrumentation, word setting, and musical pacing reflect a shrewd awareness of the countertenor’s particular strengths and qualities of range and dynamics. Among the strengths, decidedly, is one any first-rate Handelian singer must cultivate: the ability to color segments of repeated text in different ways. “Love Story” made a very apt pairing with “Nuits d’été” but will certainly reward being performed again, with or without the Berlioz. It’s worth noting that Spears and Smith have written the opera “Castor and Patience,” to be unfurled this July at Cincinnati Opera with an impressive cast: Talise Trevigne, Reginald Smith Jr., Jennifer Johnson Cano and Frederick Ballentine, led by Kazem Abdullah.

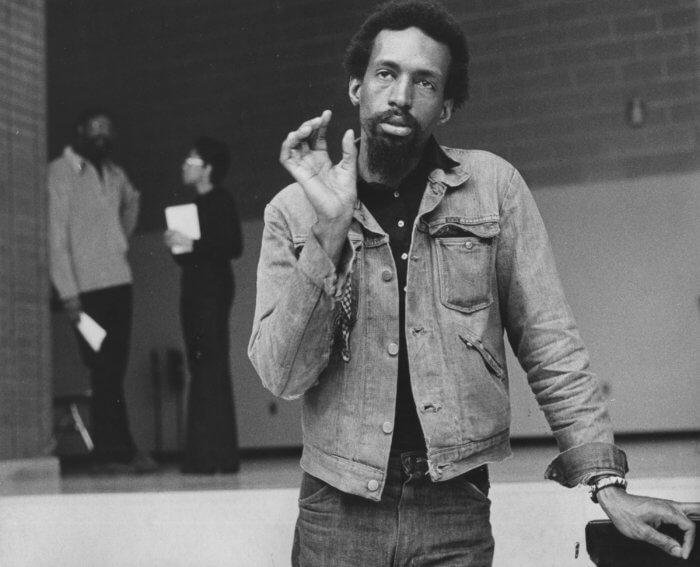

The Philharmonic’s very well planned concert closed with a powerful and sobering evocation of specifically gay desire. It focuses on Julius Eastman, a Black gay New York composer who died tragically young in 1990 after seven years of being unhoused. His final major work, 1983’s “Symphony No. II–The Faithful Friend: The Lover-Friend’s Love for the Beloved,” memorializes Eastman’s affection for poet R. Nemo Hill, to whom he gave the virtually unperformable manuscript score as a break-up gift. With the renewal of interest in Eastman’s “outsider” music, an edition of this mysterious, allusive work (a “Parsifal” theme jumps out at one point, as do intimations of orgasm) was prepared by musicologist Luciano Chessa. Van Zweden’s forces played its devastated sound wash well, the half dozen timpani players providing yeoman service on a broad range of instruments. The mid-1980s proved a bleak time for the queer community; surely in this very personal work Eastman stands with other artists like David Wojnarowicz as one of its witnesses.

Costanzo’s marathon season is by no means over. Amid several international gigs and Boston Baroque’s starry staging of Handel’s rare “Amadigi,“ (April 21-4) with Daniela Mack and Amanda Forsythe, he reprises two Metropolitan Opera roles. And true to shape-shifting form, he helps initiate this weekend’s multidisciplinary, immersive Art Bath performance art series: February 26 at Manhattan’s Blue Building.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.