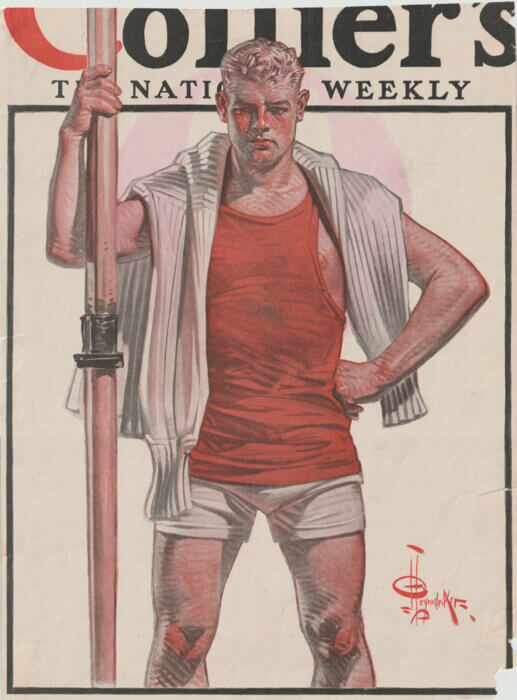

In the early decades of the 20th century, commercial culture in America was rife with imagery of robust, handsome young men exuding health and confidence, either solo or in intimate groupings. These chiseled, brooding hunks regularly appeared in print advertising campaigns for Gillette safety razors, men’s clothiers like Arrow brand shirts and Interwoven socks, and on popular magazine covers for Collier’s Weekly and The Saturday Evening Post.

The driving force behind this macho imagery was J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951), an award-winning commercial artist specializing in male figures who settled in New York in 1902. The following year he met Charles Beach, who would become his model, muse, and life partner for nearly 50 years. Many art historians have pondered: To what extent did Leyendecker’s homosexuality influence his work? How did he get away with portraying homoeroticism in mainstream publications for so many years?

Now the New-York Historical Society is considering these questions and much more with its alluring exhibition, “Under Cover: J. C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity,” on view until August 13. The show, drawn from the holdings of the National Museum of American Illustration in Newport, Rhode Island, features 19 original oil paintings and scores of illustrations by the artist. Providing context are examples of homoerotic works by other artists and a digital presentation of gay culture at the time.

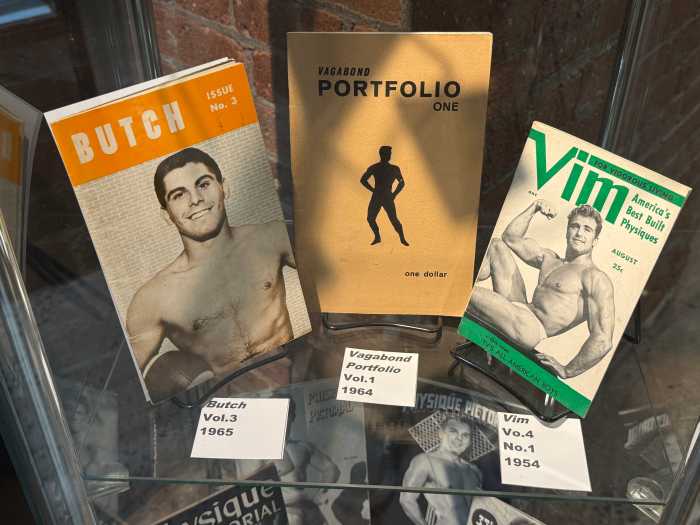

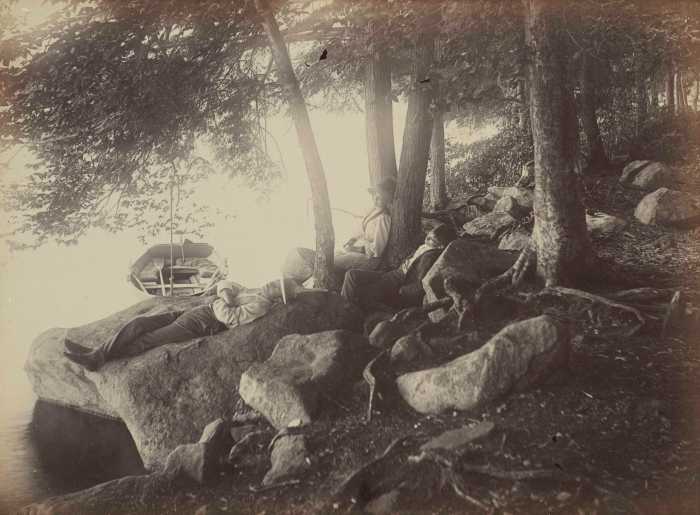

One portion of the show presents heroic depictions of male beauty, with models partly nude or wearing revealing clothes. Another investigates the coded sexual tension between men, often shown attending sporting or cultural events, or lounging in men’s clubs. There’s also a section that spotlights masculinity and World War I, describing how Leyendecker helped create governmental posters, magazine covers, and ads that boosted military recruitment and public morale. The artist produced pulse-racing images of muscular, fearless sailors and soldiers, depicting them as patriotic heroes.

“J.C. Leyendecker was an amazingly talented artist whose illustrations have come to embody the look and feel of the first half of the century while simultaneously demonstrating how fluidity in gender expression and gay representation were actually quite common at the time,” said guest curator Donald Albrecht. “Not only did his work exemplify the zeitgeist, but it depicts a deeply nuanced view of sexuality and advertising that broadens our understanding of American culture.”

As a gay artist, Leyendecker had a gift for illustrating a wide range of men from various backgrounds, from elegant dandies to lifeguards and sailors. Nearly all are idealized and physically attractive. It didn’t hurt that Beach was a stunning male specimen and served as the model for much of the artist’s work. Not just a pretty face, he also managed their business affairs.

Leyendecker is best known for creating the Arrow Collar Man, who became the epitome of sophisticated, fashion-forward masculinity. His athletes embodied the tenets of Muscular Christianity, evoking patriotic duty, discipline, and moral standards. President Theodore Roosevelt lauded Leyendecker’s work as “a superb example of the common man.” Apparently, he was oblivious to the coded homosexual undertones.

Not that Leyendecker only portrayed male figures. But when he did include a female, there is generally little warmth between the sexes. In the 1923 Arrow Collar painting of an opulent couple dancing, the gentleman appears aloof, with his sights and thoughts directed elsewhere. In scenes featuring mixed-sex groups, the presence of a woman often serves to underscore the intimacy between men. A striking example is the 1910 painting for Arrow collars of two male golfers, a woman, and a collie gathered on a marble portico. While the woman is distracted by the perky pup, the men lock gazes while holding their golf clubs suggestively erect.

It is remarkable that the Leyendecker exhibition is presented in a place of honor on the main floor, not tucked away in an upper gallery, reflecting the venerable institution’s deep commitment to LGBTQ history. Which is no surprise, really, considering that the NYHS is collaborating with the American LGBTQ+ Museum — the first of its kind — to be housed in its new wing currently in development and slated to open in 2026.

Under Cover: J. C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity | New-York Historical Society | 170 Central Park West (77th St.) | Through Aug. 13, 2023 | NYHS.org | Admission $22