A federal district judge has dismissed a right-wing lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Maryland’s ban on conversion therapy when practiced on minors.

The September 20 ruling from Judge Deborah K. Chasanow granted the state’s motion to dismiss a suit brought by Liberty Counsel on behalf of a conversion therapy practitioner challenging the state’s recently enacted law providing that “a mental health or child care practitioner may not engage in conversion therapy with an individual who is a minor.” The Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene enforces the ban through its professional licensing process

The plaintiff, Dr. Christopher Doyle, argued that the law violates his right to freedom of speech and free exercise of religion, and he had sought a preliminary injunction against the law’s operation while the litigation proceeded.

Liberty Counsel immediately announced an appeal to the Richmond-based Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which has yet to rule on a constitutional challenge against a conversion therapy ban.

Several US Circuit courts have rejected similar challenges. The New Jersey statute, signed into law by then-Governor Chris Christie in 2013, was upheld by the Philadelphia-based Third Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled that the state has the power to regulate “professional speech” as long as there was a rational basis for the regulation.

The California statute, signed into law in 2012 by then-Governor Jerry Brown, was upheld by the San Francisco-based Ninth Circuit, which characterized it as a regulation of professional conduct with only an incidental effect on speech, and thus not subject to the court’s “heightened” standard of scrutiny.

Liberty Counsel is also appealing a ruling similar to the Maryland decision by a federal court in Florida to the Atlanta-based 11th Circuit.

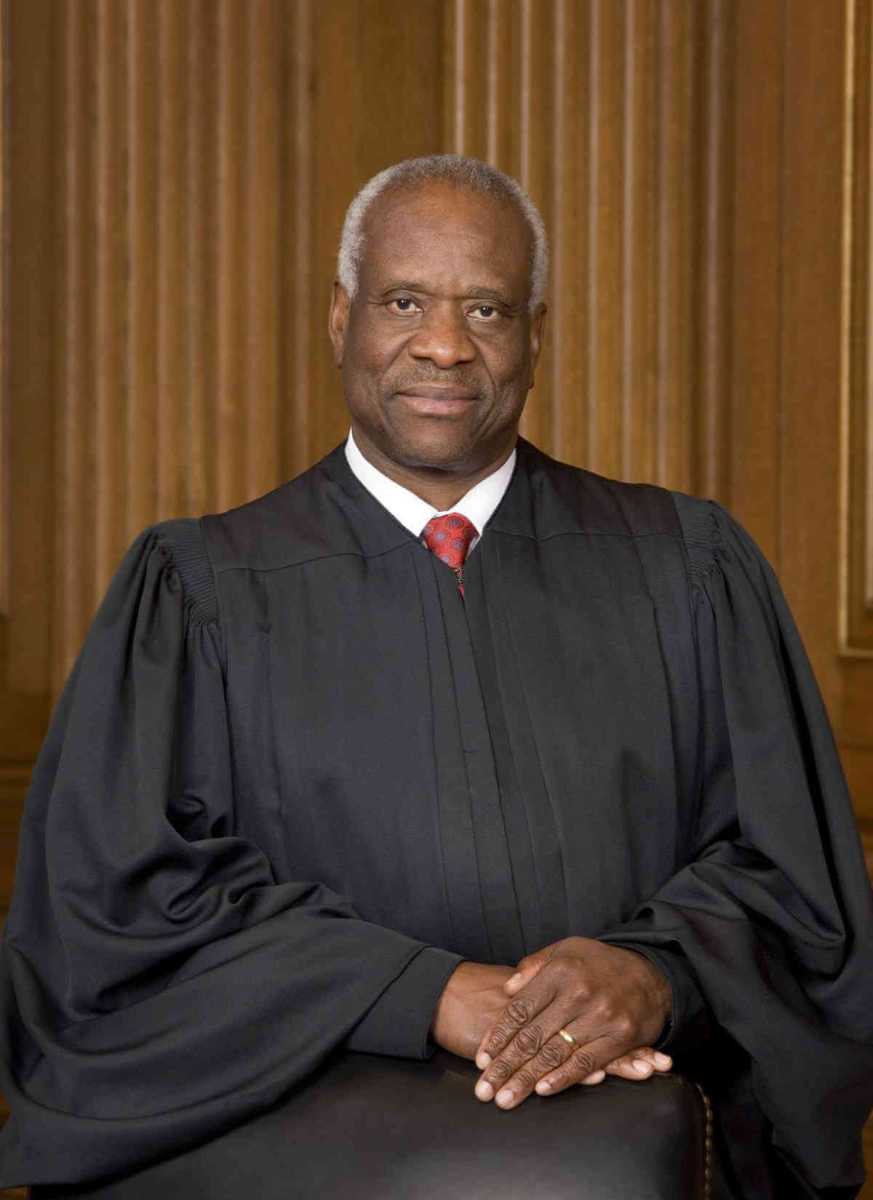

The task of protecting statutory bans on conversion therapy against such constitutional challenges was complicated in June 2018 when Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for a 5-4 majority in a case involving a California law imposing notice requirements on licensed and unlicensed pregnancy-related clinics, wrote disparagingly of the Third and Ninth Circuit conversion therapy opinions. The California statute required the clinics to post notices advising customers about pregnancy-related services, including family planning and abortion, that are available from the state, and also required non-licensed clinics to post notices stating that they were not licensed by the state.

The clinics protested that the statute imposed a content-based compelled speech obligation that violated their free speech rights and was therefore subject to “strict scrutiny.” Speech regulations of this type rarely survive a strict scrutiny constitutional challenge.

In that case, the high court reversed a decision by the Ninth Circuit, which had ruled that the notices constituted “professional speech” that was not subject to “strict scrutiny.” In his opinion, Justice Thomas rejected the idea that there is a separate category of “professional speech” that the government is free to regulate. He asserted that “this Court has not recognized ‘professional speech’ as a separate category of speech. Speech is not unprotected merely because it is uttered by ‘professionals.’”

Thomas went on to observe, “Some Court of Appeals have recognized ‘professional speech’ as a separate category of speech that is subject to different rules. These courts define ‘professionals’ as individuals who provide personalized services to clients and who are subject to ‘a generally applicable licensing and regulatory regime.’ ‘Professional speech’ is then defined as any speech by these individuals that is based on ‘[their] expert knowledge and judgment,’ or that is ‘within the confines of [the] professional relationship’” — here quoting from the Third Circuit and Ninth Circuit opinions. “So defined, these courts except professional speech from the rule that content-based regulations of speech are subject to strict scrutiny.”

After reiterating that the Supreme Court has not recognized a category of “professional speech,” Thomas conceded that there are circumstances where the court has applied “more deferential review” to “some laws that require professionals to disclose factual, noncontroversial information in their ‘commercial speech,’” and that “States may regulate professional conduct, even though that conduct incidentally involves speech.”

But, the high court majority concluded, neither of those exceptions applied to the clinic notice statute in California.

As a result of Thomas’s comments about the Third and Ninth Circuit cases, when those opinions are examined on legal research databases such as Westlaw or Lexis, there is an editorial indication that they were “abrogated” by the Supreme Court.

Based on that characterization, Liberty Counsel sought to get the Third Circuit to “reopen” the New Jersey case, but it refused to do so, and the Supreme Court declined Liberty Counsel’s request to review that decision.

Liberty Counsel and other opponents of bans on conversion therapy have now run with this language from Thomas’ opinion, trying to convince courts in new challenges to conversion therapy bans that when the practitioner claims that the therapy is provided solely as talk therapy — free of older, more coercive methods — it is subject to strict scrutiny and likely to be held unconstitutional.

The likelihood that a law will be held unconstitutional is a significant factor in whether a court will deny a defendant’s motion to dismiss a legal challenge or to grant a plaintiff’s request for a preliminary injunction against its enforcement.

Liberty Counsel used this argument to attack conversion therapy ordinances passed by the city of Boca Raton and by Palm Beach County, both in Florida, but US District Judge Robin Rosenberg rejected the attempt in a ruling issued on February 13, finding that despite Thomas’s comments, the ordinances were not subject to strict scrutiny and were unlikely to be found unconstitutional. She found that they were covered under the permissible category that Thomas recognized as being subject to regulation: where the ordinance regulated conduct in a fashion with only an incidental effect on speech.

Liberty Counsel argued against that interpretation in its more recent challenge to the Maryland law.

In its brief, it argued, “The government cannot simply relabel the speech of health professionals as ‘conduct’ in order to restrain it with less scrutiny,” and that because Doyle “primarily uses speech to provide counseling to his minor clients, the act of counseling must be construed as speech for purposes of First Amendment review.”

The problem at the heart of this legal skirmishing is drawing a line between speech and conduct, especially where the conduct consists “primarily” of speech. Judge Chasanow noted that the Fourth Circuit has explained, “When a professional asserts that the professional’s First Amendment rights ‘are at stake,’ the stringency of review slides ‘along a continuum’ from ‘public dialogue’ on one end to ‘regulation of professional conduct’ on the other.”

Chasanow continued, “Because the state has a strong interest in supervising the ethics and competence of those professions to which it lends its imprimatur, this sliding-scale review applies to traditional occupations, such as medicine or accounting, which are subject to comprehensive state licensing, accreditation, or disciplinary schemes. More generally, the doctrine may apply where ‘the speaker is providing personalized advice in a private setting to a paying client.’”

Then, quoting particularly from the Third Circuit’s New Jersey decision, Chasanow wrote, “Thus, Plaintiff’s free speech claim turns on ‘whether verbal communications’ become ‘conduct’ when they are used as a vehicle for mental health treatment.”

The judge found the Maryland statute “obviously regulates professionals,” and although it prohibits particular speech “in the process of conducting conversion therapy on minor clients,” it “does not prevent licensed therapists from expressing their views about conversion therapy to the public and to their [clients.]” That is, they can talk about it, but they can’t do it!

“They remain free to discuss, endorse, criticize, or recommend conversion therapy to their minor clients,” Chasanow concluded.

But, the statute is a regulation of treatment, not of the expression of opinions. And that is where the conduct/ speech line is drawn.

Chasanow found “unpersuasive” Liberty Counsel’s arguments that “conversion therapy cannot be characterized as conduct” by comparing it to aversive therapy, which goes beyond speech and clearly involves conduct, usually an attempt to condition the client’s sexual response by inducing pain or nausea at the thought of homosexuality. She pointed out that “conduct is not confined merely to physical action.” The judge focused on the goal of the treatment, reasoning that if the client presents with a goal of changing their sexual orientation, Doyle would “presumably adopt the goal of his client and provide therapeutic services that are inherently not expressive because the speech involved does not seek to communicate [Doyle’s] views” — but rather the aim of the client, or more likely the client’s parents.

The judge found that under Fourth Circuit precedents, the appropriate level of judicial review is “heightened scrutiny,” not “strict scrutiny,” and that the Maryland ordinance easily survives heightened scrutiny, because the government’s important interest in protecting minors against harmful treatment comes into play, and the legislative record shows plenty of data on the harmful effects of conversion therapy practiced on minors.

Chasanow refers to findings by the American Psychological Association Task Force, the American Psychiatric Association’s official statement on conversion therapy, a position paper from the American School Counselor Association, and articles from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the American Association of Sexuality Educations, Counselor, and Therapists. Such a rich legislative record provides strong support in meeting the state’s obligation to show it has an important interest that is substantially advanced by banning the practice of conversion therapy on minors.

The judge also rejected Liberty Counsel’s arguments that the ban was not the least restrictive way of achieving the state’s legislative goal and that it is unduly vague. It was clear to any conversion therapy practitioner what was being outlawed, Chasanow concluded.

Turning to the religious freedom argument, she found that the statute is neutral on its face regarding religion. It prohibits all licensed therapists from providing this therapy “without mention of or regard for their religion,” and Liberty Counsel’s complaint “failed to provide facts indicating that the ‘object of the statute was to burden practices because of their religious motivation.’”

Chasanow also rejected the argument that this was not a generally applicable law because it was aimed only at licensed practitioners. Like most of the laws that have been passed banning conversion therapy, the Maryland law does not apply to religious counselors who are not licensed health care practitioners. Because the law regulates the health care profession, its application to those within the profession is logical and has nothing to do with religion. As a result, the free exercise claim falls away under the Supreme Court’s precedent that there is no free exercise exemption from complying with religiously-neutral state laws.