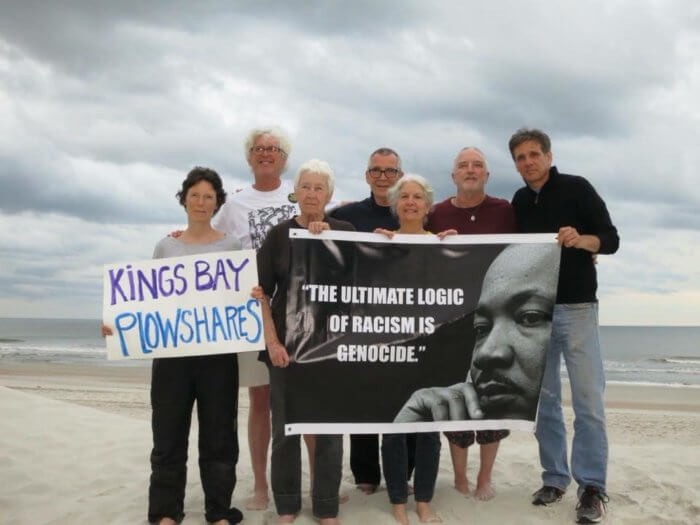

April 4, 2018, 50 years after Martin Luther King’s murder: Seven white, aging Catholic peace activists cut a fence and enter Georgia’s Kings Bay Naval Base, the largest nuclear submarine base in the world. They carry hammers and bottles of their own blood to deface nuclear monuments and banners decrying “omnicide” — the unimaginable destruction promised by nuclear weapons, not only of human life, but of life on Earth. They read a statement, repenting of “the sin of white supremacy” and resisting US “militarism that has employed violence to enforce global domination.”

They’re arrested and thrown into jail.

Heartfelt and daring, this protest was meant to be known around the world. It’s barely been noticed.

This Plowshares 7 action is just the latest in decades of nonviolent, Catholic-led protests, wielding hammers, blood, and banners, begging the world to pay attention to the increasing threat of nuclear war.

Said Clare Grady, 62, a Plowshares 7 defendant, “When I was younger, if you had this anti-nuclear awakening, there were any number of activist choices. That doesn’t exist now, except for some older white people still doing it — it’s definitely not cool.”

Lifelong peace, racial justice activist two months ahead of her federal prison sentence

Since Plowshares actions began in 1980, many arrests, convictions, and much jail time have accrued. On November 12, Clare was sentenced to one year and a day. She’s due to report to federal prison in February.

I also fear nuclear weapons, energy, and accidents. Yet I’ve done almost nothing to speak up about this. That’s why I called Clare at her home in upstate Ithaca and asked her about her life. Here’s what she told me:

An Irish Thing

I was born and raised in the Bronx. My dad was the child of Irish immigrants. His mother was a maid her entire life and never lost her Irish brogue.

My dad was underground a lot, doing draft resistance, draft board actions. The FBI were always trying to catch him; they’d come to our apartment. The neighborhood kids had a fun time, calling them flatfoot and things, ‘cause they were so obvious. But my nana was: [speaking in brogue] “Go away, will ye?” My childhood was filled with these experiences, which is perhaps unusual for people that look like me.

This was the late ‘60s, early ‘70s. My dad was part of the Camden 28 [anti-Vietnam War activists charged in a 1971 raid on the Camden, New Jersey, draft board], so he was hugely on J. Edgar Hoover’s wanted list. The FBI referred to my dad as “Quicksilver” because he kept evading them. He was always in — I guess you’d call it “good trouble” these days.

Our mom had five kids and more than anything loved being a mother and being in the Bronx. She was from Chicago, so she didn’t talk like everybody else’s muthah.

We grew up with dear, beloved friends — almost all of whom we’re still in touch with. It was really a tight neighborhood. I went to John Philip Sousa Jr. High School, and Angela Davis was on everybody’s minds then, like the Black Panthers. My school was maybe 10 percent white, with the rest Black and Puerto Rican. We have good times now, connecting over our childhoods and what it looked like from different perspectives.

My mom supported my dad ‘cause he was underground so much. Us kids knew he was underground. It’s an Irish thing — we had this friend from Ireland, Lonnie Donegan, who’d come over here to do music. He’d warn us: [brogue] “Tell them nothing.”

Because we’d been colonized for 700 years. So there was this culture already in place, and our dad — even though he was born in the Bronx — identified with the Irish rebel more than anything.

He was arrested during that Camden raid and put right in jail. I remember they brought him into the courthouse. Everybody was chained, shackled together, walking through the hallway to the courtroom, singing Irish rebel songs. He was surrounded by a bunch of other first-generation Irish people whose mothers were very connected to the resistance in Ireland. Like, never lose your roots?

The Monster Won’t Decapitate Itself

We moved to Ithaca when I was going into 10th grade. While it was breathtakingly beautiful, this Cayuga land where I lived, I was feeling the lack of the Bronx. I was in high school here three years, then I went back to New York City and joined the United Farm Workers. I was waitressing, taking classes at Hunter College, living on the Lower East Side. Then in 1980, Plowshares 8 happened [an action at the General Electric Nuclear Missile Re-entry Division in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania].

When I heard about that, I thought: “Trying to get the United States government to disarm is like asking a monster to decapitate itself. Just not gonna happen.”

Then I realized, “They’re not asking the US government; they’re doing it themselves.” It was so liberating. That began a revisiting of my family tradition, nonviolent Catholic action. I saw it as not opposed to other actions, like collective bargaining and strikes, but as something different, that can absolutely energize a situation.

Back in Ithaca, I’d had a social studies teacher, Mr. Kane, little white guy, God bless him. He had us read “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” — he was the only teacher in that school who’d do such a thing — and had us watch footage of Hiroshima’s atomic bombing. Until then, it’d been pretty much classified. I’d already done some study; I knew the dangers of nuclear weapons.

Then in November 1982, my 19-year-old sister Ellen and my 21-year-old brother John did the Plowshares 4 action [at the General Dynamics Electric Boat Shipyard, in Groton, Connecticut]. Going to the trial of my brother and my sister, I saw so clearly how the court was protecting the weapons and shutting out the truth about their mere existence.

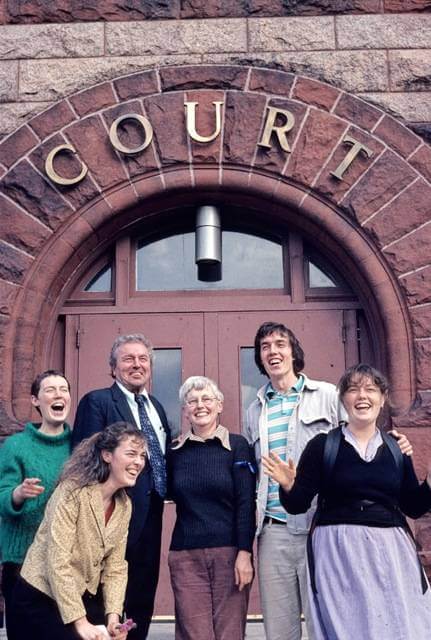

So in November ‘83, on Thanksgiving Day, I acted with the Plowshares at the Strategic Air Command at Griffiss Air Force Base in Rome, New York. It was the home of the B-52 bombers we’d used in Vietnam to rain down death and suffering. They were being refitted to carry first-strike cruise missiles. We hammered on the doors of those bombers. Seven of us were charged with sabotage and put on trial in Syracuse federal court.

We were acquitted of sabotage — which was huge, ‘cause it carried 25 years — but found guilty of destroying government property. Three of us women were given two-year sentences because we didn’t have college degrees, and four were given three-year sentences because they shoulda known better — as insulting as that. Four of us were sent to Alderson for 18 months. That was my first time being in prison.

What’s important for me is that I was living my life. So when I got out of prison, I came back to Ithaca and worked at a community kitchen, Loaves and Fishes, for like 17 years, while my kids were being born. I literally went into labor there.

When my kids were in their early teens, I was part of this symbolic action on St. Patrick’s Day in 2003 [at the Lansing, New York, military recruitment center], at the dawn of Shock and Awe. We simply poured our blood in a vestibule, right? The feds indicted us and I ended up spending time in FCC Philly for that.

Racial Justice Essential

Then, in Ithaca, there was a murder by a white cop just two blocks from where I live. I looked out my window and, because of the life I’d lived, I could see at a glance the police had done something terrible — they had killed this Black man, Shawn Greenwood. I was on two collectives for justice for him — this was before Black Lives Matter. This standing up for racial justice gets neglected by most of us white people. Even when we know better, even when our parents didn’t raise us like that, we forget that racial justice is essential.

I was at Standing Rock. My time working with water protectors there was profound. The Red Warrior Camp put out a video and said, if you do nonviolent direct action, we want you to come.

Two things to know. One, Standing Rock resistance was started by the youth. Two, they explicitly wanted it to be rooted in prayer. That was rarely translated by the time it got to the East Coast. There was this symbolic action of saying prayers at the frontline. I’m like, “I am not Indigenous; this is not my land. But I’m glad to see people doing this and not apologizing for it.”

The older I get, I see the swirling of how the creator connects us in these weavings. It reinforces my sense that no one person is expendable, but no one is carrying it all, either. Your imagination is not big enough to carry what’s unfolding.

Holding Back Armageddon

The blood that we poured at Kings Bay Naval Base? I’m part of a community where blood is used as a symbol of atonement. It cuts through intellectual brain fog. It’s also not a big deal, the blood’s drawn by a nurse and it’s stored carefully. We took a little of our blood in small bottles, and we took hammers — household hammers — and spray-paint and bolt cutters and banners. We brought three to Kings Bay.

You know, the Trident is literally the most deadly weapon on this planet. There are 14 Trident nuclear submarines, with six at Kings Bay. That’s their homeport. Our factsheet says, among other things, that each of those submarines can carry 24 ballistic missiles. Each missile can carry up to eight 100-kiloton nuclear warheads — or about 30 times the explosive force of the Hiroshima bomb.

Most people have no idea. Honestly, I don’t think about it every day. I try to act humanly in the face of what I know, and emphasize the positive part of what I feel we’re called to do. I’m trusting that universal spirit is holding back Armageddon for us to get our stuff together.

Finally, after centuries of work by people of color, we have Black Lives Matter — finally, we have these awakenings. I feel like we’re on the cusp of something. My hope is that we start to weave in how nuclear weapons are connected. For me, they’re the billy club of the planet — the enforcement mechanism of white supremacy and global capitalism. They’re used, 24/7, to extract resources, labor, and life.

In my sentencing statement I called on Dr. King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech, where he identifies the giant triplets of racism, militarism, and extreme materialism. I said I took a nonviolent disarmament action because the Trident is killing in my name. It doesn’t just kill if it’s launched, it kills every day. Indigenous people are some of the first victims — the mining, refining, testing, and dumping of radioactive material for nuclear weapons happens on Native Land…

I knew, even though the judge could get pissed off and give me more time, that I wasn’t just speaking to the judge. I got 12 months and a day. I just got the papers, I report on February 10. They’re still deciding where to send me. It’s crazy; I’m really scared of being in prison during COVID. But people can get stuck on, “Oh, poor you.”

Actually, it’s all of us. If you have any kind of privilege or power, use it because we’re on this cusp now. Listen to the voices of the Hibakusha, the survivors of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Learn how we’ve used nuclear weapons — what did that look like? What does it look like now?

Listen to the scientists who are telling us, “Hey, we have 100 seconds to midnight…” Then connect the dots to Indigenous people and people of color who have been on the frontlines of this violence daily.

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.