A monument honoring LGBTQ icons Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera will be erected down the street from the Stonewall Inn, the city announced on May 30.

The monument will reside at Ruth Wittenberg Triangle at 421 Sixth Avenue at Christopher Street and Greenwich Avenue and will be the product of the She Built NYC initiative through women.nyc, a project led by First Lady Chirlane McCray that sought opinion from the public regarding which women the city should honor.

The monument will honor the historical significance and longtime commitment to LGBTQ rights of the two activists, who were major figures in the local fight in the decades following Stonewall — a pivotal period that saw not only the political aftermath of the riots but the emergence of the AIDS crisis, as well.

Political leaders, trans activists, and members of the wider LGBTQ community gathered at the LGBT Community Center on May 30 to formally announce plans for the monument. Mayor Bill de Blasio, McCray, the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs, “Pose” star Angelica Ross, and out gay city lawmakers Corey Johnson, Daniel Dromm, and Jimmy Van Bramer were among those on hand, as well as Marsha P. Johnson’s nephew, Al Michaels.

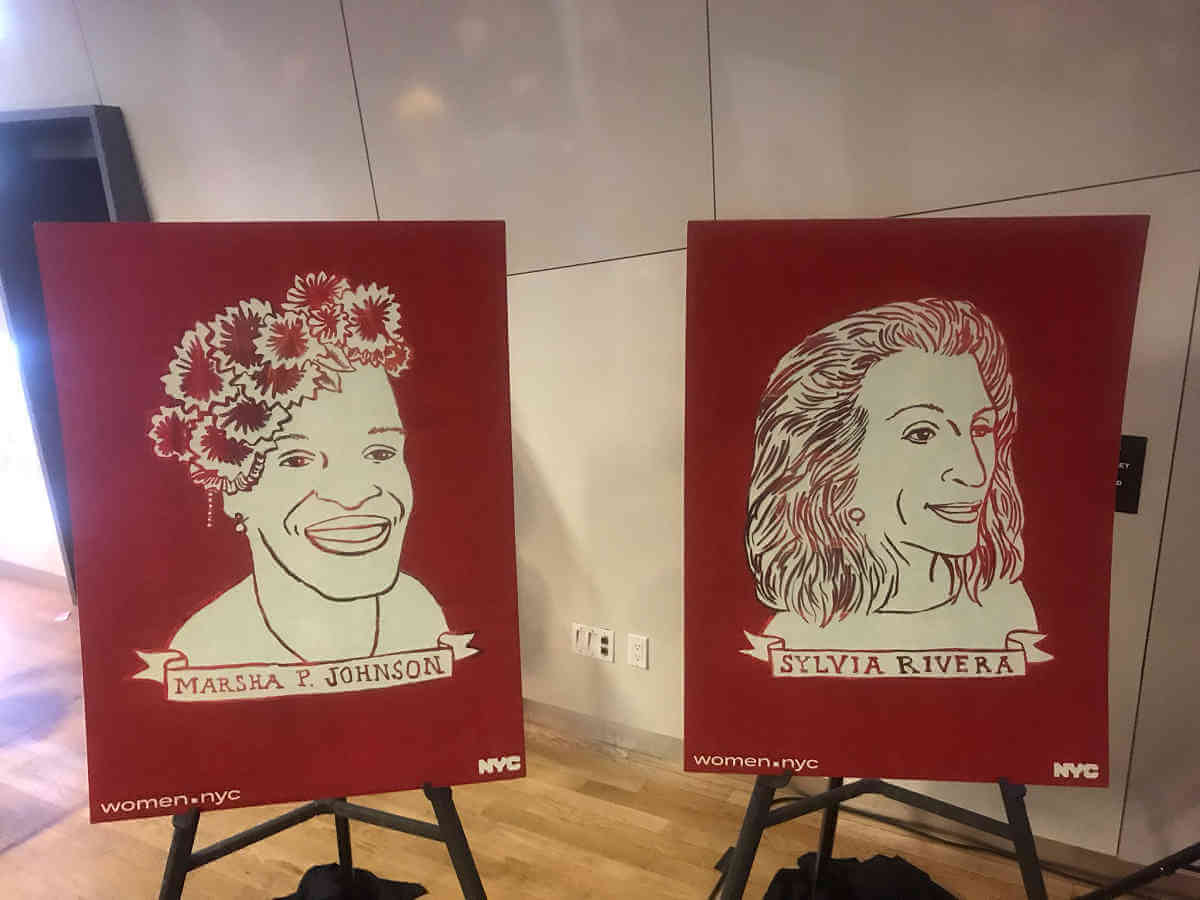

“Our history helps define our present and shapes our future,” McCray said, as artwork depicting Rivera and Johnson was unveiled by Matthew McMorrow, an out gay senior aide to the mayor. “The contributions of too many women, LGBTQ people, people of color, and people living on the margins of society have been obscured or erased entirely… These stories must be told, heard, and celebrated.”

McCray added, “Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera are undeniably two of the most important foremothers of the modern LGBTQ movement.”

Michaels, Johnson’s nephew, stepped to the podium and reflected on his aunt’s legacy. He recalled her vibrant personality and care for others, saying that she told him never to apologize for who he was.

“She had $15 in her pocket, and with that $15 she became mayor of Greenwich Village, started a revolution, and sadly died a violent death,” Michaels said. “But today Marsha and Sylvia are having their day, getting their monument. If that’s not a New York story, I don’t know what is.”

Cecilia Gentili, a trans leader who served as the director of policy at GMHC and has founded Transgender Equity Consulting, became emotional as she stressed the importance of creating monuments honoring trans people, including trans people of color.

“Me, as a trans person, I see myself reflected,” Gentili said, wiping away tears. “Me, as a person of color, I see myself reflected. Me, as a former sex worker, I see myself reflected. Me, as a person who lived in this city for 10 years as an undocumented person, I see myself reflected.”

Elected officials praised the work of Rivera and Johnson and pushed for the advancement of transgender rights and visibility in the years to come. Council Speaker Johnson underscored the importance of not just electing new LGBTQ councilmembers, but also finally electing trans councilmembers, while Van Bramer told a story from 2000 when he was arrested for protesting the St. Patrick’s Day Parade and wound up spending his time in jail next to Rivera.

“At 3 o’clock in the morning as I was in a cell, I heard the legendary Sylvia Rivera giving it to the police officers in a way that could not be repeated right now,” Van Bramer, who represents the Queens neighborhoods of Sunnyside, Woodside, Long Island City, Astoria, and Dutch Kills. “They were having a discourse about where she should be placed. They said she should be placed with the men. She said, ‘Bullshit. That’s not where I’m going.’”

The She Built NYC Committee, which recommended the monument for Johnson and Rivera, noted in a written statement that Rivera and Johnson’s “determination and commitment to coalition building have made New York City, the nation, and world more just and fair.”

She Built NYC has already approved the design for a monument to Shirley Chisolm, the first black woman elected to Congress, slated for Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, while four other women — blues singer Billie Holiday, mid-19th century civil rights pioneer Elizabeth Jennings Graham, Dr. Helen Rodríguez Trías, the first Latina president of the American Public Health Association, and 19th century German-American lighthouse keeper Katherine Walker — have also been chosen to be honored with monuments.

Johnson and Rivera were active in post-Stonewall political organizing efforts at both the Gay Activists Alliance and the more radical Gay Liberation Front. Outspoken in their advocacy for queer youth, people of color, and gender nonconforming folks, the pair soon became disenchanted with what they viewed as their invisibility in GAA and GLF. In 1970, they formed STAR, the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, a short-lived organization that focused on demanding change while providing shelter and food for homeless queer youth and young adults. STAR briefly maintained a shelter for young people in the East Village.

The use of the name transvestite at that time reflected the evolutionary nature of both Johnson and Rivera’s self-identification and of gender nonconforming people’s self-identification as a group. Though both Johnson and Rivera came to self-identify as transgender women, historical accounts of their activities in the years just before and after Stonewall have them presenting alternately in men and women’s styles.

A critical question raised by their monument being located near the Stonewall Inn and announced on the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots is what role each woman played in the events of late June 1969.

Historical and scholarly sources universally agree that Johnson was at Stonewall at the time of the initial police raid. David Carter, whose 2004 book “Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution” is the most thoroughly researched history of the June ‘69 events, concluded that Johnson was likely among the very first bar patrons to actively resist, in violent fashion, the NYPD raid.

Rivera’s claims to have been involved are more problematic. Eric Marcus and Martin Duberman, who both wrote histories in the early 1990s that were based largely on interviews with the subjects they were chronicling gave credence to Rivera’s accounts of her involvement. Carter, on the other hand, omitted Rivera from his book altogether, and later told GayToday.com, “I am afraid that I could only conclude that Sylvia’s account of her being there on the first night was a fabrication.”

Carter pointed to the lack of corroboration from “credible witnesses who saw her there on the first night,” to several intimates of Johnson’s who said she told them that Rivera was not there, and to the changing nature of Rivera’s accounts of that night. In one telling, bar patrons were pelting cops with pennies and quarters; in others, they, improbably, had Molotov cocktails at their disposal.

Randy Wicker, an out gay man who became involved in LGBTQ rights activism in the 1950s and lived with both Rivera and Johnson, told Gay City News on the morning of May 30 that the discussion surrounding who was or was not at Stonewall shouldn’t overshadow the recent news about the city erecting a monument. But he nonetheless recalled what Johnson told him about the night when Stonewall protests commenced.

“Marsha herself, she never really discussed Stonewall beyond that she was there and that it was when her gay activism started,” Wicker said. “But I think the reality is they were both there. Bob Kohler and Marsha said Sylvia came down later in the night while it was still going on and she was very taken up with the fight and I’m sure all her activist instincts came in.”

The truth about the events surrounding Stonewall have become, over the past 50 years, notably contentious, and considerable care is warranted in trying to tell the story. The New York Times, which was given an exclusive about the monument’s announcement by the de Blasio administration a day ahead of the May 30 announcement, didn’t even try to tackle this question. Instead, using the journalistically dubious device of the passive voice, the newspaper reported, “They are also believed to have been key figures in the June 1969 Stonewall Uprising.”

For some, the nuances of these historical questions apparently seem to be a distraction from what they see as a larger truth. McCray, the mayor’s wife who in 1979 penned an essay for Essence Magazine titled “I Am a Lesbian,” told the Times, “The LGBTQ movement was portrayed very much as a white, gay male movement. This monument counters that trend of whitewashing the history.” At the May 30 press conference, McCray said that Rivera and Johnson played “a leading role at Stonewall.”

Whether or not history has been whitewashed, there is no doubt that Johnson, born in 1945 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and Rivera, born in 1951 in the Bronx, were seminal figures in New York’s LGBTQ history. After youths in which they survived through sex work, the two were determined, passionate, often angry advocates for marginalized communities. Johnson continued as an organizer throughout her life and was active in ACT UP during her final years, though people who knew her were also aware of her struggles with mental health challenges, issues chronicled in news reports and histories of the LGBTQ movement.

Days after the 1992 LGBTQ Pride March, Johnson’s body was found floating in the Hudson River. Though her death was officially ruled a suicide, some of her friends, including Rivera, suspected foul play, and rumors of a fight being witnessed and a man claiming to have killed “a drag queen named Marsha” have been repeated for years.

Rivera moved in and out of activism after the immediate post-Stonewall years. By the 1990s, however, she had revived STAR, in part to focus attention on what is now recognized as an epidemic of violence against trans women. Author Michael Bronski chronicled her battle with the LGBT Community Center over what she saw as its neglect of queer youth — a fight that had her banned from the Center for a period of time in the ‘90s. As New York State moved toward adopting a gay rights law early in this century, she was outspoken in her anger at established queer leaders who left gender identity out of that measure — an omission only rectified this year.

No less an activist than Riki Anne Wilchins, writing in the Village Voice in 2002, the year of Rivera’s death from liver cancer, said, “In many ways, Sylvia was the Rosa Parks of the modern transgender movement, a term that was not even coined until two decades after Stonewall.”

As for the monument, city officials say a designer has not yet been determined — but Wicker said there should be at least one requirement.

“While I really doubt it, I would like to know if there are any trans people involved,” he said. “A trans person should design a monument like that.”