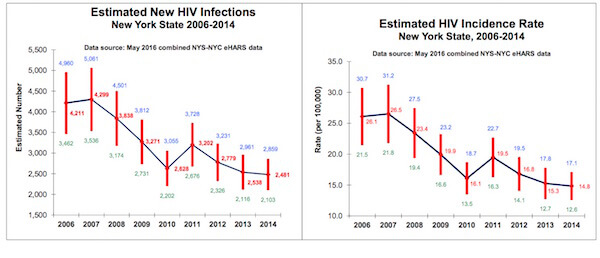

New York State health department estimates of new HIV infections and incidence rate of new infections from 2006-2014. | NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

Citing an increase in the number of HIV-positive people who have no detectable virus in their blood and an estimated decline in the number of new HIV infections in New York that occurred before the state spent any money on a plan to reduce new HIV infections in the state to 750 a year by 2020, the Cuomo administration is saying that these data nevertheless represent a milestone for the Plan to End AIDS.

“New York State is leading the fight against HIV and AIDS, and these results display extraordinary progress toward our overall goal of ending the epidemic,” Governor Andrew Cuomo said in a July 13 press release. “We are working toward making New York, once the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic, a place where new infections are rare and those living with the disease can enjoy a full, normal, and healthy life.”

The state health department, which receives the results of all HIV viral load tests performed on New York residents, reported that in 2014, 77,000 HIV-positive New Yorkers had no detectable virus in their blood versus 71,000 in 2013. In 2014, the state estimated that 123,000 people were HIV-positive in New York. Several recent studies found that a person who is undetectable cannot infect others.

Efficacy claims obscure ongoing battle for state money to end epidemic by 2020

The state health department also estimated that there were 2,481 new HIV infections in the state in 2014, which represents a 42 percent decline from the estimated 4,300 new HIV infections in 2007.

To create the estimate of new HIV infections, the state health department tests the blood of some people who are newly diagnosed as HIV-positive with assays that determine how recently the individual was infected. Using that sample, the state health department estimates how many of the new HIV diagnoses in a given year are new infections that occurred in that year.

While most press reported the 2,481 estimate as the number of new HIV infections in 2014, the state health department produced a range indicating that the estimated new HIV infections in 2014 could be as high as 2,859 or as low as 2,103. The range was not disclosed in the July 13 press release though the state website contained links to the complete data.

There were an estimated 4,211 new HIV infections in 2006, which fell to to 2,628 in 2010 and then climbed to 3,202 in 2011, so a good portion of the decline to 2,481 is accounted for in new infections declining since the 2011 spike.

“The [Plan to End AIDS] initiative, which began in 2014, built upon an already comprehensive state-supported HIV/ AIDS prevention and care infrastructure, thereby enabling the rapid uptake of… programming and the realization of early gains in the State’s effort to end AIDS as an epidemic by the end of 2020,” a state health department spokesperson wrote in an email.

Over 90 percent of the new HIV infections in New York occur in New York City. In 2014, the city health department reported 2,718 new HIV diagnoses in the city and, of those, 488, or 18 percent, received an AIDS diagnosis, which indicates a later stage of HIV infection, at the time those people first learned they were HIV-positive. People who receive a concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis likely went untested for many years.

In 2014, 3,434 New Yorkers were newly diagnosed as HIV-positive, according to the state health department. Using the 2,481 estimate suggests that 953, or 27 percent, of those people were infected before 2014. Comparing that percentage to the city’s 18 percent is not an apples to apples comparison, but it might indicate that the state is being generous in its estimates of how sharp the new infections decline has been.

The Plan to End AIDS uses anti-HIV drugs in HIV-positive people to reduce their viral loads to an undetectable level and in HIV-negative people to keep them uninfected. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) are the two drug regimens used in HIV-negative people.

Cuomo first endorsed the Plan to End AIDS in mid-2014. The state did not fund the plan until 2015 and even then advocates said the amount fell well below what was needed to fully fund the plan. AIDS groups still need Cuomo’s help on money and legislation. They have been largely unwilling to criticize Cuomo until this year, when he was the subject of protests in Albany and in New York City.

“Basically, we’re trying to strike a fine balance between vigorous and relentless pressure with even handed patience,” Mikola De Roo, a spokesperson at Housing Works, an AIDS services group, wrote in a March 2015 email that was among documents obtained by Gay City News in a Freedom of Information request made to the city’s Office of Management and Budget. “There will be plenty of opportunities in coming weeks and months to turn the heat up more and hit the Governor harder and for the harder punch to be far more effective than it would be right now.”

The July 13 press release quoted Charles King, the chief executive at Housing Works, along with five other chief executives at AIDS or health groups. King is credited with developing the Plan to End AIDS along with Mark Harrington, the chief executive at the Treatment Action Group, a health policy organization.

Also quoted in the press release were Kelsey Louie, the chief executive at GMHC, Benjamin Bashein, who heads ACRIA, an HIV research and educational organization, and Wendy Stark, the head of the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center.