Baptist pastor’s work with Lower Manhattan school raises questions about blurred lines

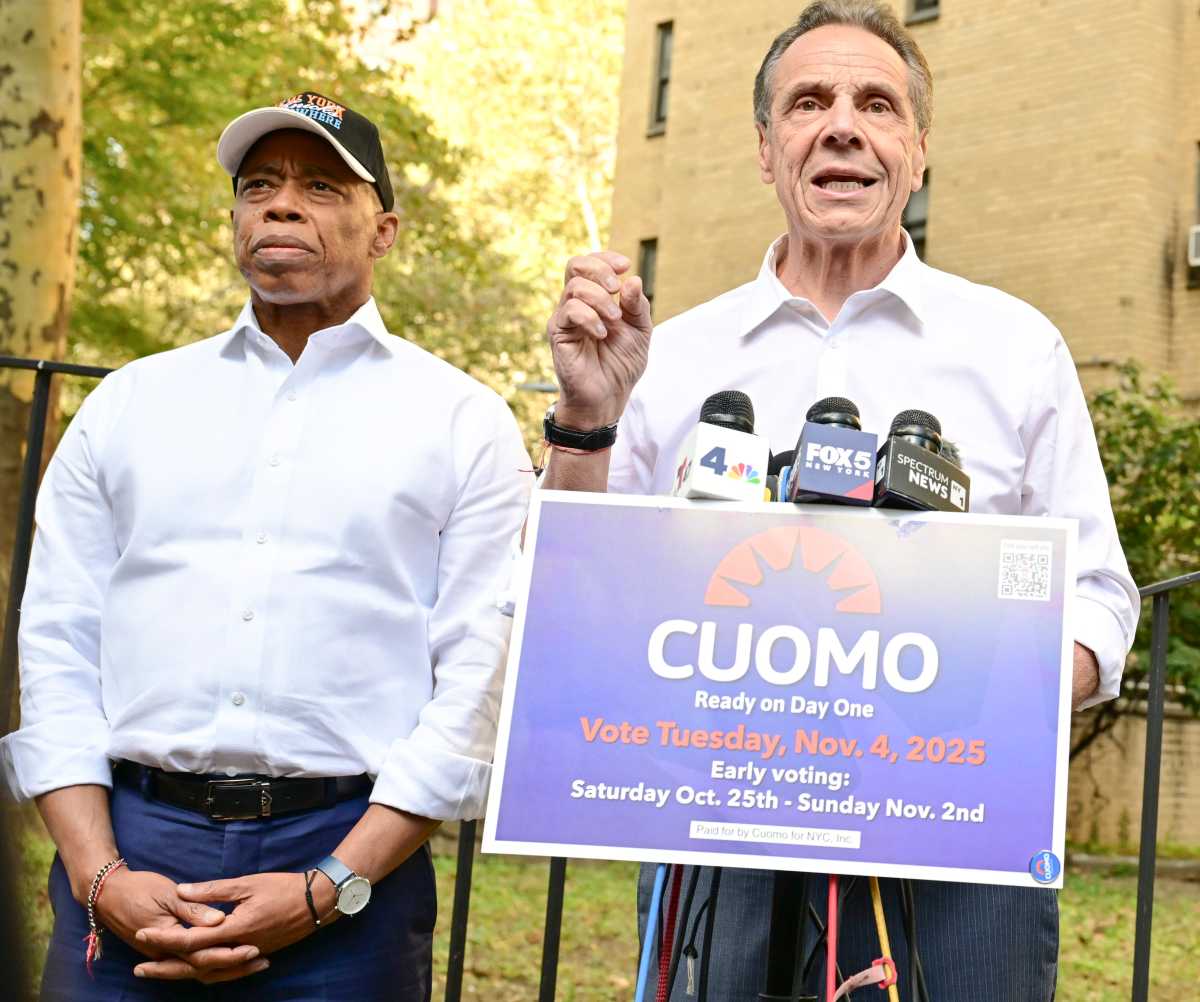

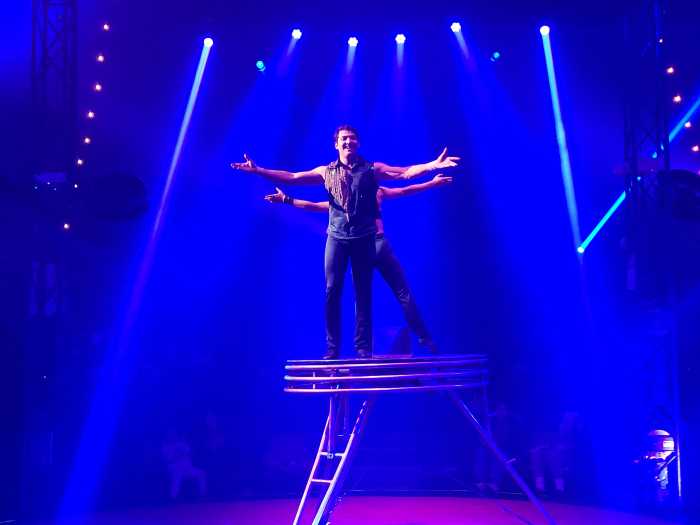

With strobe lights flashing, three zealous parishioners competed in a game of “who can hold a box over his head the longest” while a Christian rock band reminiscent of the not-so-Christian White Stripes blasted through a squeaky-clean version of the reggae classic, “I Can See Clearly Now”—in the auditorium of PS 89 in Battery Park City.

The church, Mosaic Manhattan, has been able to hold its services at the school for the past year and a half because of a 2002 federal court ruling that directed the city Department of Education that if public school space is offered out for rent, it must be made available to religious institutions on the same basis it is to any other group.

But when Mosaic helped fund three PTA and other school events at PS 89, some community members objected to the church’s generous financial donation and its distribution of religious materials and legal experts are now wondering whether the court ruling threatens to blur the boundary between church and state.

On Sundays, PS 89 transforms into a church, with large colorful Mosaic Manhattan Church banners—bearing a cross—hanging from the playground fence and church members directing parishioners to the school’s second floor. The services are festive affairs led by pastor Gregg Farah, a youthful, lanky minister and native New Yorker whose chatty, engaging preaching is reminiscent of his time as a high school teacher in Seattle. Farah has co-authored two books—“Fruit of the Spirit: God’s Word for a Junior High World” and “Risk It!: Daring to Act on the Truth of God”—and also moonlights as a stand-up comic in Greenwich Village.

Mosaic’s morning and evening services draw upwards of 300 worshippers combined from Battery Park City and other nearby neighborhoods. Most of the parishioners are young—in their late teens to mid-twenties.

“We just fit in really well, which goes a long way for New York,” said Heidi Powers, a slight 24-year-old with elaborate tattoos trailing the lengths of both arms. She moved to Alphabet City from California with her husband, Kurt, a year ago. Kurt plays in a band, Sex Sells, and performs in the church band from time to time.

“They’re not afraid to have us be part of the image of their church,” Heidi pointed out.

Mosaic is part of a larger movement within the Southern Baptist Convention to bring evangelical churches to 21 million people in the greater New York City area, a movement that was accelerated after 9/11 when nearly 4,000 volunteers were mobilized from around the country to help in relief efforts. Baptist leaders realized that the city was short on evangelical houses of worship.

“If you filled every church in New York City, there would still be 10 million people who wouldn’t have a place to worship,” said Dave Howard, executive director of New Hope New York, a group founded by the North American Mission Board in Atlanta that sees itself as a “church planting” organization. New Hope has helped found 20 new churches in New York City since its August 2001 inception—including Mosaic.

In founding Mosaic, Farah received help not only from New Hope, but also from eight Southern Baptist congregations and from Redeemer Presbyterian Church, which in 2000 also launched a church planting effort to “develop a large, influential, orthodox Protestant Christian community… to saturate greater New York with Gospel-centered churches,” according to its Web site.

“This is God’s timing!” Farah said. “My wife and I were figuring out how to get back to New York. We were looking for a place to minister and they [the Southern Baptist Convention] were looking for a church.”

Mosaic has a modern approach to delivering a conservative message. Its services include game show-like activities, video images projected on a screen and a band that plays a combination of Christian songs and popular, uplifting favorites. With the parishioners seated comfortably in the auditorium, Mosaic feels very different from a traditional church.

“We are liberal in our methodology and conservative in our theology,” Farah said in an interview.

That conservatism applies to homosexuality, on which Farah has a “hate the sin, love the sinner” perspective. As a youth pastor in California, he wrote a column for teenage boys on Crosswalk.com, a Christian Web site. “With teenage boys it’s usually about sex, sex and well, sex,” Farah said. In one issue, he counseled an adolescent conflicted about his sexuality: “You know homosexuality is wrong and the Bible agrees with you,” he wrote. “But are you aware that God is crazy about you?”

Farah has brought that approach to Mosaic. “Whether you are homosexual or not, we’re going to help you love God,” he said. “Let God speak to you about your lifestyle.”

Mosaic takes a similarly conservative stance on heterosexual sex outside of marriage.

“If you are not married you should abstain, if you’ve been having sex, you should abstain from this point forward,” Farah said of his advice to single parishioners.

Farah is also a parent of three daughters, all of whom attend PS 89. When his church contributed $5,000 to the PTA’s 2003 Welcome Back to School party and distributed balloons emblazoned with Mosaic’s cross-embedded logo and church literature, some parents balked at what they saw as a violation of separation of church and state.

“I felt like I was in a new production of the ‘Stepford Wives,’” said Tom Goodkind, a Battery Park City resident and PS 89 parent of the event. According to Goodkind, the balloons and flyers were distributed to the children with little fanfare.

“It just didn’t seem appropriate for a religious group to be handing out these flyers with balloons and crucifixes in a school setting.” Although the event was not on school property—it was at Pier 25 in Tribeca—it was in fact sanctioned by the PTA

The school and PTA turned to the Department of Education for direction.

“We were treating [Farah] like any sponsor in that we were giving him airtime,” said Pamela Tucker, fundraising chairwoman for the PS 89 PTA “It made many of the parents uncomfortable.”

The Department of Education, following the advice of its legal team, told the school that it could accept donations from the church, but Mosaic should not distribute its materials at any school event.

Last month, Mosaic donated $2,500 to the Welcome Back to School party, which was held on school property, but agreed not to distribute balloons, literature or have a booth.

For Ronnie Najjar, principal of PS 89, the issue involves not only a tenant of the building, but also an involved parent in the school. In attempting to address the anxieties of concerned parents while still respecting Farah’s desire to involve his parish with the school—and respect the federal court ruling—Najjar treads lightly.

“Some of the parents who are objecting [to the Back to School parties], object to using schools for places of worship and there’s something to that. I won’t say it’s an unfounded objection,” she said. “[But] Mosaic has a right to be in the school.”

Ellen Foote, principal of IS 89, housed in the same Battery Park City building, worries that at some point a school-sanctioned activity, such as a weekend study group, will coincide with a religious service in nearby classroom, a situation that she thinks might influence non-church going children, making it difficult to distinguish between the school-sponsored and church-sponsored activities.

“I can’t think of any other type of activity that we would permit in the school that would give rise to that kind of concern,” said Foote.

For some skeptical parents, Mosaic’s new, lower profile at PTA events does not relieve their anxiety about the church’s level of influence on their children.

“For those of us who don’t happen to be Protestant, which is probably the majority of us, to have a Southern Baptist group with that kind of presence is tasteless,” said Goodkind.

Some legal and religious analysts agree with Goodkind’s concern, arguing that the very presence of the church in the school can lead to an uncomfortable relationship between school and religious officials.

“If you can’t tell the difference between the church doing a good thing for the school and a parent doing a good thing for the school then you have a problem,” said Reverend W. Fredrick Wooden, senior minister at First Unitarian Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

When told of Mosaic’s involvement in school events, Wooden said it would be hard to separate Gregg Farah the pastor from Gregg Farah the parent.

“The power of religion is so strong that we need to be more transparent and more vigilant about that than other forms of power,” Wooden argued. “When the church and the state come close, it becomes ever more important to maintain the transparency of who is speaking for whom so the people who are affected can go either to the state or the church and ask them to give account.”

Some church members, in fact, have encountered skepticism from Mosaic-wary PS 89 parents when participating in school events. When Katie Ferdinand, a PS 89 parent and Mosaic member, agreed to direct the school’s talent show last year, Mosaic reached out to her and offered to supply the sound system and loaded it for the event—which took place in the school auditorium. When Ferdinand received a phone call from a suspicious parent, she was taken aback.

“So I go to that church,” said Ferdinand, a former stage director. “I’m hosting the talent show, I will not be handing out Bibles at the talent show.”

Beth Haroules, a staff attorney for the New York Civil Liberties Union holds the school—not the church—accountable for maintaining a clear boundary between church and state. Although she was not familiar with the particulars of Mosaic, she voiced concern about church-sponsored PTA events.

“The school has started down this dangerous path that looks to be the school endorsing this religious message,” she said. “The church has the right to engage in proselytizing, but the school should not be allowing them to have access to a school-sponsored event.”

The banners hanging from the school’s playground fence on Sunday mornings was also worrisome, she said, because they too suggested an endorsement from the school.

Other observers also voice concerns.

“Our system of education was not designed to be supported by churches,” said Susan Jacoby, author of “Freethinkers: A History of American Secularism” and director of Center for Inquiry-Metro New York, a secular think tank based in Massachusetts. “Public officials should not be in the business of judging which religions to have on their public premises and which not to.”

But for Farah, the issue of using a school auditorium for his services is pure economics. When he went looking for affordable space in Battery Park City, he found few options. The United Artists movie theater demanded early hours and the hotel lobbies were too costly at $1,500 per rental. So he looked to his daughters’ school, PS 89, where he could rent the auditorium and cafeteria for $300 per morning. Mosaic’s operating budget for 2004 is $588,504, according to Farah. With two services a week, the church now pays the Department of Education about $30,000 a year in rent, a fraction of what it would pay elsewhere.

State Assemblywoman Deborah Glick, a lesbian who represents portions of Lower Manhattan that include Greenwich Village argues that cost and lack of space has little to do with the original federal lawsuit, filed by the Alliance Defense Fund (ADF), that opened the schools to religious organizations.

“This is an effort on the part of ultra conservative legal organizations specifically intending to blur that distinction” between church and state, she said. “Churches are tax-exempt institutions. It is not as if there is no vehicle or no other alternative location for churches.”

ADF, headquartered in Scottsdale, Arizona, is a legal advocacy group that counts among its “founding ministries” the Focus on the Family—headed up by Dr. James Dobson, one of the most strictly conservative of the nation’s Christian right leaders—and the Campus Crusade for Christ.

Some PS 89 parents approached Glick following the 2003 party at which crucifix-emblazoned balloons were distributed. Since the issue was addressed by the Department of Education and the 2002 court ruling is still under appeal, Glick said she has taken no action regarding the matter.