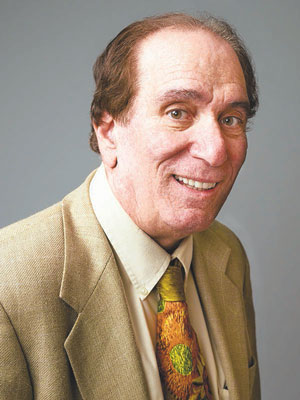

DR. THEO: Long Island oncologist and hematologist Dr. Michael Theodorakis has been treating cancer patients for nearly 40 years. North Shore Hematology Oncology Associates

A patient of Dr. Michael Theodorakis, a cancer and blood specialist on Long Island, was stunned to learn that the lump on his chest was breast cancer.

“He had no idea. He thought breast cancer was a woman’s disease,” said the oncologist and hematologist at North Shore Hematology Oncology Associates in East Setauket with nearly 40 years in the trenches of research, treatment, and education.

The patient fit the mold of men at risk for the deadly disease: He was in his 70s and tests on his siblings showed half of them had the same breast cancer susceptibility gene — known as “BRCA” — that prompted actress Angelina Jolie to undergo a preventive double mastectomy last year.

The man survived, after his breast and under-arm lymph nodes were removed, but others males may not be as lucky — breast cancer will strike 2,360 men this year and 430 of them will die, states the American Cancer Society.

Add to that another chilling fact about the killer disease.

“I’ve seen people cured with breast cancer for 25 years, only to see it return,” said Theodorakis, who specializes in breast cancer, lymphoma, and leukemia, and teaches oncology and hematology at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

The good news is survivorship is increasing due to exciting, new discoveries unthinkable a few decades ago. Chemotherapy drugs were just developing and most cancer sufferers received the same treatments when Theodorakis — known as Dr. Theo to his patients — began his career in the late 1970s. Cancer specialists are realizing today that our genes have the master plan of life. Big or small, dimpled or not, blonde or brunette, man or woman, our genes pretty much spell out our health destiny, and modern therapies are guided missiles, deploying pharmacogenomics or the role of genetics in drug response to tailor individual remedies.

“We’ll be able to take a tissue sample and test it against a number of drugs to see which ones are likely to work and which ones won’t,” said Theodorakis. “But we’re not quite there yet.”

Factors such as advancing age and having your first child after 30 can increase the risks of breast cancer, but the more than 2.8 million survivors in the United States today — more than at any other time in our history — are testaments to the game-changing breakthroughs:

• 1970s: Multiple chemotherapy drugs are used for the first time, yielding higher response rates. Lumpectomies done collectively with radiation reduce the need for mastectomies.

• 1980s: New drug therapies result in better responses, increasing the chance of survival.

• 1990s: Discovery of a powerful group of compounds known as taxanes increases our ability to kill cancer cells.

• 2000s: Hormones known as aromatase inhibitors are found to stop the production of estrogen in postmenopausal women, reducing their risk of breast cancer. Scientists discover breast cancer is a number of diseases — not one, as previously thought — caused by hormones, radiation, genetics, a virus, or other factors.

• 2010s: Targeted therapies destroy cancerous cells, but spare normal ones.

Awareness and education remain some of our most powerful weapons against breast cancer, said Theodorakis, who advises patients to exercise, maintain a moderate weight through healthy diet, know their family’s medical history, and get tested using the five-year gauge: if your sibling was diagnosed with breast cancer at 38, then you should have your first mammogram at 33.

The future indicates that science and humans are forging formidable alliances to produce even better outcomes.

“The people I used to see die are now living,” said Theodorakis.

North Shore Hematology Oncology Associates [235 N. Belle Mead Rd. in East Setauket, (631) 751–3000, www.nshoa.com].