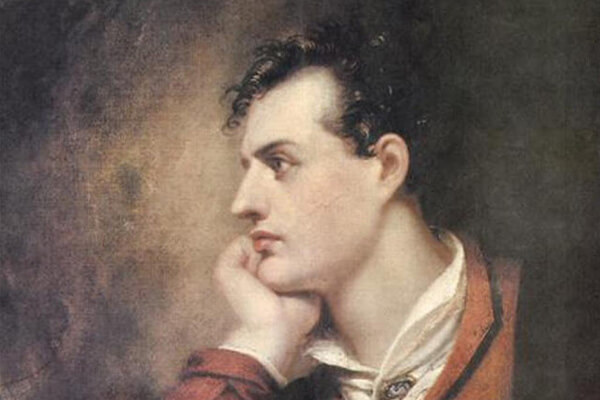

Poor Lord Byron. The most famous of the English Romantic poets continues to be a source of scandalous speculation two centuries after his premature death from an unknown fever at the age of 36 in 1824. Fighting, at the time of his death, for the liberation from Turkish rule of Greece, he remains a national hero there to this day.

A new novel raises once again the question of Byron’s sexuality.

“Childish Loves, “ recently published by W.W. Norton, is the third novel in a Byronic trilogy by Benjamin Markovits, a Texan who, after a career that embraced both playing basketball and teaching high school, went on to study the Romantics and now teaches at the University of London.

Surprisingly, given the respectful critical attention the trilogy’s two previous entries received, “Childish Loves” has been reviewed only sparingly. Perhaps this is because the publisher has chosen to sensationalize Byron’s sexual orientation in presenting the book. “Was Byron a pedophile?” shrieks the press release, which Norton put out at the time of the book’s publication last fall.

Given that repugnant sexual predators in powerful positions who abuse their authority to molest little children — from the Catholic Church to Penn State’s Jerry Sandusky to the Horace Mann School in the Bronx — continue to make headlines nearly every day, book review editors may be skittish about taking up a volume that deals, however briefly, with the love of boys.

“Childish Loves” uses the device of a story within the story to explore Byron’s sexuality. In the novel, a character named Ben Markovits — who, like the author of “Childish Loves,” is married with two children and lives in London — becomes the literary executor of Peter Sullivan, a former colleague of his at an all-male private school, among whose papers he finds fragments of a reimagining of Byron’s diaries.

“Childish Loves” alternates between three of those fragments and the Markovits character’s attempts to research a biography of Sullivan, whose own life had been marked by a sexually-tinged incident of some sort with one of his teenage charges at a different school from the one two men worked at together.

In pre-gay liberation days, a canard often heard was that queer writers could not successfully portray heterosexual relationships — the homophobic diatribes of the noted critic Stanley Kauffman come to mind as a particularly obnoxious example of this sort of thinking. The falsity of such assertions is, of course, disproven by a host of queer writers, from E.M. Forster to Tennessee Williams, to name but two among many.

“Childish Loves” raises for me a different question — can someone bereft of any same-sex experience fully convey with complete understanding the queer plight? I say this as much because of what “Childish Loves” leaves out as for what it says.

Which brings me to Louis Crompton, a giant in gay historiography and the author of what remains the single most minutely researched and authoritative exploration of the same-sex affinities of the celebrated Regency poet — 1978’s “Byron and Greek Love: Homophobia in 19th Century England” (University of California Press).

Crompton had already established himself as a Shaw scholar of note when, in 1970, he began teaching the second course in gay studies anywhere in the country at the University of Nebraska, where he was a professor of English for decades. This course created such a political firestorm from the homophobic Republicans — then as now, in control of the State Legislature — who attacked Crompton’s course for “using taxpayers’ dollars to teach perversion to our kids.” The course was cancelled.

Undeterred, Crompton continued to pour out a raft of books and articles on gay history, including his magnum opus, 2003’s “Homosexuality and Civilization.” It is to Crompton, who died in 2009 at the age of 84, that we owe the rediscovery of the famous 18th and early 19th century English law reformer and philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s extensive writings in defense of homosexuality and its legalization.

In “Byron and Greek Love,” Crompton documented how persecution of homosexuals had reached an unprecedented zenith in the Regency years and under King George III and IV as Byron was growing up and coming to manhood. Hangings for homosexuality increased, but even more so did the horrific torture known as the pillory.

Men who were convicted of “attempted” sodomy were dragged through the streets and put into stocks, where they would be pelted by enormous crowds with rotten fish and meat entrails, mudballs, rotten fruit, and stones. Hawkers made money by passing through the crowds of assembled queer-bashers to sell them objects to be thrown at the men being pilloried. These events received considerable attention in the press of the day. Police entrapment was employed to catch suspected queers, who were frequently maimed or blinded after having been pelted in their pillories.

One of the most notorious cases in the late 18th century, which would have been much talked about during Byron’s boyhood, was the scandal surrounding William Beckford, considered the wealthiest commoner in England. A novelist (notably, his “Vathek”), art collector, and patron, Beckford was accused of sexual relations with a youth of 16. The resulting scandal, which enflamed the press, drove Beckford into exile, a route that many homosexuals were also to take in those years.

As Crompton reported, “When Byron left England on his first trip abroad, almost his first act on the continent was to visit the mansion where Beckford had lived in exile at Cintra, near Lisbon.” In lines included in Canto I of the work that made him famous, ‘Childe Harold,’ but suppressed by him and not published until nine years after his death, Byron described Beckford’s mansion:

“Unhappy Vathek! In an evil hour

Gainst Nature’s voice seduced to deed accurst.

Once Fortune’s minion, now thou feel’st her Power!

Wrath’s vials on thy lofty head have burst:

In wit, in genius, as in wealth the first,

How wondrous bright thy morn arose

But thou were smitten with unhallowed thirst

Of nameless crime, and thy sad day must close

To scorn, and Solitude unsought — the worst of woes.”

These lines, as Crompton rightly noted, “show how fully Byron was aware of the social sanctions visited on homosexuals and bisexuals in English society and how little wealth, talent, and position availed to protect any man who was once suspect.”

They also explain the use of homophobic condemnations in them, which were necessary to protect any author who, however obliquely, referred to homosexuality.

Although the Markovits character in “Childish Loves” says that Crompton’s “Byron and Greek Love” was one of many books on the poet he’d read in his search for the truth about his friend Sullivan and the nature of both his and Byron’s sexuality, the homophobia that drove Byron out of England is reduced to a one-sentence observation that sodomy was then a capital crime. Nor is there any reference to homophobia being Byron’s motivation for so often changing the gender of the love objects in his poems from male to female. It is astonishing to me that Markovits, the novelist, could have been so unmoved by Crompton’s terrifying descriptions of the persecutions and tortures meted out to same-sexers in Byron’s day.

While Byron had many brief affairs with women (he’d been initiated into heterosex at the age of nine by a female house servant) and eventually contracted an unhappy marriage (perhaps for protection as well as money) and fathered a child, there is little doubt that one of the other reasons for his self-exile and eventual settling in Greece was to be able to practice the “vice” for which Beckford was condemned.

Nor is there any doubt that the greatest love of Byron’s life was John Eddlestone, to whom he wrote so many poems. Byron was only 17 and had just gone up to Cambridge for his university studies when he met Eddlestone, a choirboy of 15. Only an uncultivated imbecile could characterize a sexual and emotional relationship between a 17-year-old and a 15-year-old as “pedophilia,” as Norton suggests. Byron was, to be completely accurate, an ephebophile. One could also call him a pederast, the Merriam-Webster definition of which is “someone who enjoys anal intercourse, especially with boys.” (In France, queers call each other “pédés” — short for “pédérastes” — regardless of their sexual partners’ age.)

Cambridge was the university of the country’s elite, and his affair with Eddlestone became the subject of gossip that would follow him down through the years and help impel his permanent self-exile. Eddlestone returned Byron’s love and wanted to live together with him permanently — an impossibility in those days, of course, as both boys would have been subjected to prosecution. Nor could he accompany Byron in his European travels.

Shortly after his return to England in 1811, Byron received a letter from Eddlestone’s sister Ann telling him that the lad had died of consumption and assuring Byron of his continuing place in the young man’s affection. Byron was devastated at the news and over the next five months wrote a series of seven elegies for him, in which he called Eddlestone “Thyrza.”

In the first of them, Byron wrote:

“Ere call’d for a time away,

Affection’s mingling tears were ours

Ours too the glance none saw beside

The smile none else might understand;

The whisper’d thought of hearts allied,

The presence of the thrilling hand.”

One of the little coterie of homoerotically inclined young men Byron had gathered around himself at Cambridge was John Cam Hobhouse, who remained his lifelong friend, confidant, traveling companion — and censor. Hobhouse was politically ambitious, eventually getting himself elected to Parliament and winding up in the cabinet as secretary for war.

It was Hobhouse who persuaded Byron, after their university years were done, to burn his Cambridge journals — presumably because they were too explicit about his relationship with Eddlestone. And it was Hobhouse who, after Byron’s death, insisted on burning Byron’s memoirs, correspondence, and certain unpublished poems. Hobhouse was trying not only to protect Byron’s reputation, but his own — his close friendship with the poet was too well-known and Hobhouse’s own adventures in homosexuality would have been inferred, something no politician could then have survived. Still, the novelist Markovits makes no mention of the role homophobia played in the burning of Byron’s papers.

In one of the reimagined Byron journal entries in the novel, Byron reveals that his first same-sex encounter was with Lord Grey, who had rented the family’s manse. Though several biographers suggest Grey may have made a pass at the young Byron, it is far more likely that he engaged in his first male-male sexual experiences at Harrow, the elite private school that had a reputation as a hothouse of buggery. There, Byron’s first poems were all addressed to other boys for whom he had what he called “passions.”

Why did Greece hold such fascination for Byron and his friends? If you don’t have the patience to read the ancient Greek poets — Euripedes, Horace (“Horatian” was one of the Byron set’s code words for same-sex love), or Anacreon (how many Americans know that the music for our National Anthem was taken from a drinking song honoring that old poof, “To Anacreon in Heaven”?), then you should read the masterful cycle of historical Hellenic novels by Mary Renault, which are as fine an evocation of that ancient world as anything Robert Graves ever produced and which — from “The Last of the Wine” to “The Persian Boy” — portray a society in which same-sex love was honored and respected. It was for this ideal that Byron and his male chums yearned. Here, too, Markovits’ novel fails.

As many critics have remarked, Markovits has an undeniable talent for being able to reproduce the early 19th century “voice” in his writings. But his failure to be able to empathize fully with those who engage in same-sex love cripples this book. The Markovits character in “Childish Loves” describes the imagined account of the seduction of the teenage Byron by Lord Grey (who in real life would have been 24 at the time of the time of their sharing a bed together) as a “rape” — when the relevant passages do not indicate anything more than a hand job. It appears that, for all his acquired sophistications, Markovits has not yet fully cleansed himself of all his hetero Texan prejudices.

But if “Childish Loves” drives any reader to Crompton’s magnificent and convincing “Byron and Greek Love” — the book is unfortunately out of print and richly merits a new edition — then this new Byronic novel will have served a useful purpose.

CHILDISH LOVE | By Benjamin Markovits | W. W. Norton Paperback Original | $14.95 | 397 pages