It was 2022 and I was on my first post-pandemic trip abroad, for work. I had a day-long stopover in Istanbul, and seized the opportunity to take a speedy look-see around this ancient metropolis whence many a beloved friend, dear neighbor, and valued colleague hails. Walking briskly between two of the city’s defining landmarks, the Hagia Sophia Mosque and the Sultan Ahmed, or Blue, Mosque, I was descended upon by one of the many tour guides in that area, intent on gaining my business.“Wait! Stop!” he bellowed, sidling up alongside me, brochures in hand. “What I have to tell you is important!” I smiled and kept booking. He scurried ahead to turn and face me. “You look like Hot Chocolate!” he said. Presumably, this was a spontaneous marketing pitch. He was not referring to the beverage (although it did cross my mind that he was), but to the British disco-era band by the same name whose lead singer, Errol Brown, was a man who happened to be Black, have a shaved head and a thick mustache, just like … me?

I could not help but recall that encounter while taking in the exhibition, “Turkey Saved My Life – Baldwin in Istanbul, 1961–1971,” currently on view at the Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) through March 15. Some 60 years before my brush with that expressive tour guide, James Baldwin, the towering American author and civil rights advocate, had resided there in the “Queen of Cities,” as the Byzantines dubbed it. Among street vendors and shoe shiners, beside minarets and monuments, crossing old bridges and building new ones, Baldwin pushed through a bout of depression that had him blocked creatively to complete his bestselling novel, “Another Country” and work on other notable books, among them his classic essay collection, “The Fire Next Time.” For this reason, he later told an interviewer, “Turkey saved my life.”

The BPL’s exhibition is among several homages to James Baldwin mounted around the city, country, and overseas in commemoration of what would have been the author’s 100th year. Baldwin was born in New York City in 1924 and died of cancer in France in 1987. This exhibition focuses on a lesser-known slice of his life, the decade he spent in Turkey, and why. The 2010 book of University of Michigan professor Magdalena J. Zaborowska, one of the foremost scholars on Baldwin, “James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile,” provides the informational backbone of the exhibition. While the show is organized around the claim that “living abroad, in a country that straddles both west and east, would allow Baldwin to gain critical distance from his home country and its ubiquitous racism and homophobia,” it does not, perhaps cannot, address the ways in which Baldwin was viewed racially in Istanbul. Did he have a “Hot Chocolate” encounter of his own? What was it and how did he react to it?

Baldwin never wrote about Istanbul in either fiction or essay, as he did, for instance, of his experience sojourning in a town in the Swiss Alps in the early ’50s where children, consumed with fascination at his presence, ran behind him, calling out, “Neger!” (Black!). Zaborowska attempted in her interviewing of Baldwin’s Turkish friends and associates to tease out answers to this question, as poet Reginald Harris, who reviewed her book upon its release, wrote: “Zaborowska … does not let comments like those of friend and actress Zeynap Oral that because race and sexuality were ‘not talked about, therefore it did not matter,’ pass lightly. When Zaborowska tries to press for details of … societal attitudes toward this dark black man in the country, his friends remain evasive: ‘When words like “Arap” (Arab) or “Yamyam” (Turkish for cannibal) or even the n-word rolled off tongues easily, I was told, they were used warmly and jokingly as ‘terms of endearment.’”

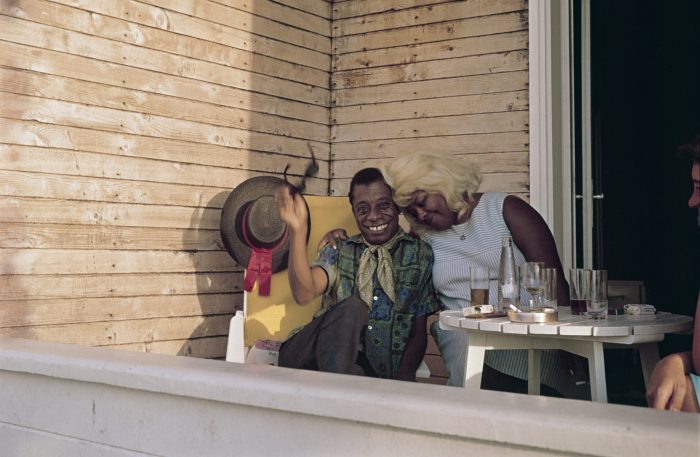

Installed in the library’s main lobby and mezzanine, the exhibition consists primarily of photographs, most in black and white, of Baldwin alone as well as with friends in private or strangers in public. In one, a lone Baldwin is shown from the back, removing his shoes to enter a mosque. His stance — balancing on one foot — is symbolic of the less-than fully grounded awareness many readers of Baldwin have of this decade in the writer’s life, whose expatriate years in France and Switzerland are better known. A highly evocative photo is a close-up of Baldwin’s face from below as he takes in the grandeur of the interior of the Blue Mosque.

The images were taken by Turkish photographer and filmmaker Sedat Pakay. Pakay’s interest in photographing Baldwin was sparked at the age of 19 by a newspaper article he stumbled across in his college library announcing the imminent arrival in Istanbul of the acclaimed author. Pakay was magnetized by Baldwin’s face, and set his sights on studying the man through his lens. In addition to years of photographing Baldwin in various locations around Turkey, Pakay shot the film, “James Baldwin: From Another Place,” stills from which are in the exhibition. Enlargements of Pakay’s contact sheets shed some light on the photographer’s creative process: Baldwin’s gestures and expressions morph from square to square, and the settings change from domestic to historic to, as sometimes indicated by Baldwin’s expression, idyllic.

James Baldwin was first invited to Istanbul by the actor Engin Cezzar, whom Baldwin had befriended after Cezzar played the role of Giovanni in a stage adaptation of Baldwin’s 1956 novel, “Giovanni’s Room.” There are several shots of the two men in the company of others in the theatre community, including Gülriz Sururi, Cezzar’s wife. In 1970, nearing what would be the end of his Istanbul years, Baldwin directed a production of the play, “Fortune and Men’s Eyes,” written by openly gay Canadian playwright John Herbert. The play, based on Herbert’s own experiences of incarceration, is about prison sex. Critics and audiences praised Baldwin’s production, which was performed entirely in Turkish, a language he had not mastered. Posters and other printed matter from the performance are on display in the exhibition.

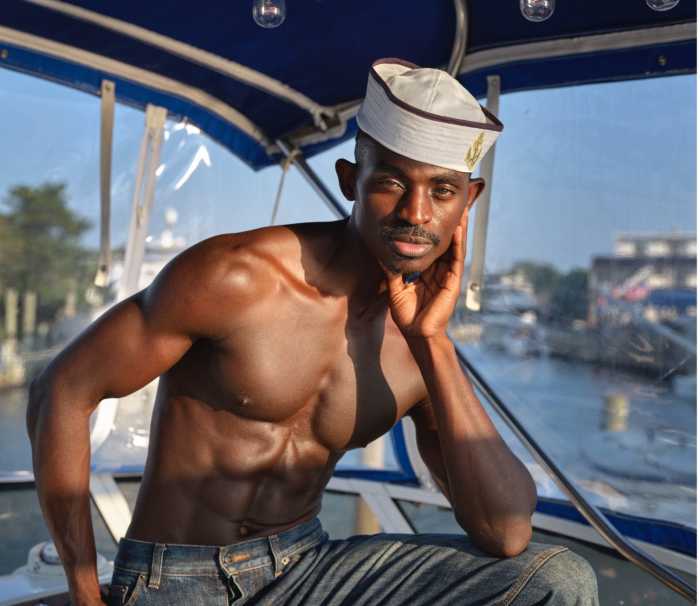

Baldwin’s social orbit in Turkey is also chronicled in this visual diary. Pakay captured him socializing with both locals and visitors from the States or elsewhere. The painter Beauford Delaney is visible, as are the actress Bertice Reading, David Adams Leeming, who was Baldwin’s assistant for some years, and David Baldwin, James’ brother and manager. All of them were, like Baldwin, expatriates. Among the locals pictured is a man identified only as “Emin, Baldwin’s swimming teacher and lover.” The photograph shows Emin with his hand on Baldwin’s shoulder outdoors at a restaurant overlooking the Bosphorus Strait.

On my brief but very enjoyable jaunt through a tiny section of Istanbul, I came across a vintage record vendor on a roadside. At the front of a couple rows of vinyl were classics from the memory vault of Black popular culture: the album “Disco Baby” by Van McCoy and the Soul City Symphony, which features the 1975 dance-music anthem, “The Hustle” and an LP of “The Flip Wilson Show,” the first successful eponymous variety show starring an African American host/performer on US television and international syndication, running from 1970 to 1974. These artifacts and images were displayed with a prominence I would be hard-pressed to find back in New York. They are simply not in public circulation so publicly anymore. There, before me, was one piece in the puzzle of my “Hot Chocolate” moment, and, perhaps, if he had one too, James Baldwin’s.

“Turkey Saved My Life – Baldwin in Istanbul, 1961-1971” | Brooklyn Public Library | Until March 15, 2025

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is a professor of media sociology at the City University of New York-Lehman College