A traumatized teen invigorates several lives, forsaking his own

Julia Jordan is on a roll. This theater season, the sizzling-hot playwright has seen four full productions of her plays in New York City—“St. Scarlet,” “Tatjana in Color,” “Summer of the Swans,” “Boy”—more than most dramatists stage in a lifetime. And she’s got other projects waiting in the wings.

With “Boy,” her current production at Primary Stages, it’s evident why Jordan is in demand. The former actor, who began writing plays after feeling embarrassed when reciting what she considered to be lousy dialogue at auditions, has a knack for pungent language that feels urgently authentic. Her characters are highly literate, adept at debating the merits of Thomas Hardy, George Eliot, and Raymond Carver. She relishes making audiences work hard, favoring ideas over mere entertainment. At times, though, the effort can be a tad too strenuous.

Jordan’s intricately provocative, but imperfect drama, spanning 24 hours in the lives of five forlorn characters, investigates the structure of stories—in books, plays, and real life. It’s about distinguishing the good endings from the bad and our innate desire to re-write the unsatisfactory ones.

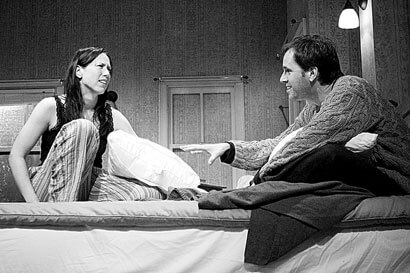

In “Boy,” each anguished character has a personal story that could surely use a re-write. There’s Mick (Kelly AuCoin), a failed actor who returns home to Minnesota after three years hoping to reunite with Sara (Miriam Shor), the girlfriend he dumped to live in New York. The driven, know-it-all Sara, in med school planning a career as a pathologist, has yet to forgive—or forget—him. Mick’s beleaguered mother Maureen (Caitlin O’Connell), who once dreamed of a tenured professorship at a prestigious university, has settled for teaching introductory English lit. to students who don’t even read the books at a local linoleum-paved community college. Mick’s depressed father, Terry (Robert Hogan), a clinical psychologist prone to red-faced fits, has more neuroses than his patients and is teetering on the edge of mental collapse.

Then there’s the Boy, who doesn’t seem to have a name, unless you count “Pothead,” the nickname his buddies called him back home in Iowa, (and later, another moniker—which I mustn’t reveal here—bestowed by the medical staff). He’s only 17, yet with a limp and other visible neural damage resulting from an incident involving an idling car and a closed garage door. The Boy appears as world-weary as Terry, his therapist. When he opens his mouth, his acid-laced words can do some major damage.

This broken Boy, who may in fact be a master manipulator, denies that he’s gay so many times it’s hard to believe him. He has written a true account of his tragic teen exploits for an English class assignment, but can’t seem to get the ending right. Guess who turns out to be his teacher?

In toying with the notion of plot structure and faulty endings, this admirably complex work scrambles scenes out of chronological order. Mick may be echoing the author’s own sentiments when he says to his mother, “There is nothing easier to write than a tragic ending that everyone can believe in. Depression is easy.” Or is he?

As the story progresses, more unexpected connections emerge. Bonds are tested, secrets are exposed, feelings are trampled. Like any good drama, “Boy” supplies the audience with multiple “ah-ha!” moments, even while the characters themselves remain clueless. There are times, however, when the dots Jordan expects us to connect are way too far apart.

At first glance, none of these characters is particularly likable, but the entire cast delivers uncommonly nuanced performances that bring just enough vulnerability and warmth to hold our interest.

With his disheveled oversized clothes and depressed slump, contrasting sharply with his rapier tongue, the Boy is one of the most engaging souls to shuffle onstage this season. After a stilted beginning, Knight’s portrayal blossoms into one of delicate pathos—we aren’t sure whether to hug him or clock him.

Despite the accomplished writing and performances, “Boy” suffers from a mild case of listless direction. The slack pacing, courtesy of Joe Calarco, comes as a surprise, since the director won high praise for his lively Shakespeare modernization, “R & J,” a few years back. There are a couple of flat, prolonged scenes that would benefit from a cut, or at least more action.

In a work obsessed with the physics of endings, it’s only natural we would be hypercritical of the conclusion of Jordan’s onstage story, which turns out to be fairly predictable. Whether it is the right ending or not is left entirely up to us.