Bill Lynch with Mayor David Dinkins and Nelson Mandela, who had recently been released from a South African prison and would go on to the presidency of that nation –– with Lynch’s assistance. | BILL LYNCH ASSOCIATES

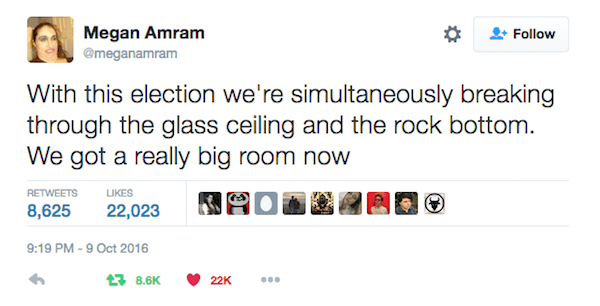

Bill Lynch, Jr., who died August 9 at age 72, has been celebrated as the “rumpled genius” who guided David Dinkins to New York’s mayoralty in 1989, a deputy mayor, the coordinator of the city’s welcome to Nelson Mandela in 1991 after he was released from prison, a consultant to Mandela’s first presidential campaign, and one of the savviest political consultants in the country, electing John Liu as comptroller and Cy Vance as Manhattan district attorney, among many high profile candidates.

I will remember Lynch as the man who gave this reporter, a young gay activist in the late 1970s, one of my first paying jobs at the NYC Self-Help Clearinghouse and then took a chance on me again in 2003 as a consultant to his firm, Bill Lynch Associates, for seven years. As a government official and civil rights activist, he was deeply involved in some of the biggest LGBT and AIDS issues of our time in addition to movements for the poor, people of color, women, children, and others.

Bill Lynch came out of the 1960s social justice movements on Long Island for migrant workers and fair representation for African Americans in government. A native of Mattituck, a black enclave on the North Fork of Long Island situated amidst miles of potato farms, Lynch would show up at meetings in those days in overalls. And forever more, one of his catch phrases in meetings was to preface his remarks by saying, “Now, I’m kind of slow and country,” when in fact he was the sharpest, quickest guy in the room.

“Rumpled genius,” “indispensable man” of New York politics was committed LGBT, AIDS advocate

At his packed memorial service at the Riverside Church on August 15, Reverend James Forbes called him “a principled pragmatic.” Hillary Clinton credited his coordination of the 1992 Democratic Convention in New York that nominated her husband as “putting the wind at our backs” for the rest of that campaign. “He was old school” as a consultant, she said. “He was a numbers guy before computers, but he knew there were things that defied measurement,” such as the “personal connections” he made to people who sought “to live lives of value and dignity.”

Clinton also said that Lynch would say to people thinking of running for office, “If you’re not trying to win, don’t call me. What do you want the job for?”

Bill Clinton said, “I remember he had eyes like a vacuum cleaner, staring a hole through me. He was judging me. I was coming up a little short, but he’d say, ‘You’re okay. You just have to deliver.’”

The former president added, “The most important thing he did was to prove politics could be a noble endeavor.”

Bill Lynch in September 2010 after managing Congressman Charlie Rangel’s Democratic primary victory despite the veteran Harlem lawmaker’s House censure. | ANDY HUMM

Reverend Al Sharpton said Lynch’s “integrity was rare. He would talk to us when we weren’t talking to each other,” telling advocates to “stop the pettiness. He demanded we be bigger. He forced bigness out of small people.”

David Dinkins called him “one of the greatest men I have every known.” He recalled how Lynch, who suffered from a variety of long-term ailments, including diabetes, and required dialysis, “played through pain few of us can imagine.”

Patrick Gaspard, Lynch’s former protégé — and there were many — and now President Barack Obama’s nominee for ambassador to South Africa, called Lynch “a beautiful mess of a man” who “knew that organizing people was more art than science.” In politics, he said, “Bill didn’t pick winners, he made winners.”

Reverend Jesse Jackson called Lynch “a force of nature” and hailed his recent work organizing people to fight the stop and frisk tactics of the NYPD, which days after his death were limited by a federal judge.

Len Riggio, CEO of Barnes and Noble and a close friend, said Lynch called him once about a Senate candidate. “‘I can’t hear you, Bill. What’s that siren?’ He said it was an ambulance. I said, ‘Wait until it passes.’ He said, ‘I can’t. I’m in it.’”

That was Bill Lynch, working to the end and enjoying many bonus years despite ill health because his son Billy donated a kidney to him.

Few remember his days as an agitator, leading the fight to keep Harlem’s Sydenham Hospital open in 1980. He also led sit-ins at the Board of Education in the early ‘80s to demand a chancellor of color. In 1983, Anthony Alvarado, a Latino, won that post and was followed a string of other people of color.

As host of a radio show called “Illuminations” in the early ‘80s, he put one of the first people with AIDS on the air — a white gay man. Lynch leaned into the guy at the top of the show and asked him, “How does it feel to be a nigger?”

The anger of AIDS activists at Mayor Ed Koch boiled over in the 1989 election and despite several credible opponents, the vast majority of LGBT and AIDS activists got behind Dinkins, who won 51 percent in the primary and then beat Rudy Giuliani. As deputy mayor and political point person in the Dinkins administration, it wasn’t all smooth sailing for Lynch. But the administration got behind condoms and explicit AIDS education in the schools, started a registry for domestic partners, and settled a lawsuit by giving all city employees domestic partner benefits.

One of Dinkins’ finest hours was standing with the Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization in 1991 in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, enduring jeers and tossed beer cans. Lynch negotiated the compromise that let ILGO march without its banner, but within Manhattan’s Division 7 of the Ancient Order of Hibernians. When the parade committee then did everything they could to keep ILGO out of subsequent parades, Dinkins joined the boycott of it. ILGO, however, rejected Lynch’s pressure not to sit-in in protest of its exclusion the following year, leading to the largest mass arrest of LGBT people in the New York’s history.

Lynch had a terrific sense of humor. Once when I offered some advice to a client at a meeting we were at together, he played off me saying, “Don’t listen to him. He’s just trying to get you in trouble.”

Bill Lynch was not a saint and made a good living, but he did so much good in his lifetime that the full house for his funeral at the massive Riverside evoked a response very few others could. When Wynton Marsalis on trumpet slowly walked up the aisle playing the most mournful and moving “Amazing Grace” I have ever heard, there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.

Lynch was, in the estimation of many, the indispensable man in New York politics — the guy who could get everyone in the room and make things happen for the good. When the Tea Party was outflanking progressives across the nation, he got his union allies and the NAACP to organize a mass rally in Washington in 2010. When Gay Men’s Health Crisis couldn’t get its new landlord to finalize its lease, he helped his old colleague Marjorie Hill, the LGBT liaison in the Dinkins administration, to get the deal done.

Bill Lynch is survived by his wife, Mary, son William Lynch III, daughter Stacy, daughter-in-law Rashanna Lynch, and a grandson, William Lynch IV.