A Bettye Lane photo of the 1969 Stonewall uprising. | BETTYELANE.COM

Bettye Lane, a news photographer with a keen eye for the average people who organized mass actions to stop the Viet Nam War and liberate women and LGBT people, died September 19, her birthday. A longtime resident of the Westbeth artists’ complex in Greenwich Village, she was 82.

Lesbian author and activist Sarah Schulman wrote in an email, “From the time I started attending Gay Liberation demonstrations while in high school in the 1970s, Bettye Lane was always there, silently snapping with agility and a focused gravitas. Many times she was the only photographer who thought these events merited documentation. And her photos from the era are classics, showing women, men, trans people, drag, and the people of color intrinsic to the movement at the time. Having your photo taken at a gay event was risky business at the time — perhaps that's why I was so aware of her presence. We never spoke but she was a force of preservation, saving those moments for a very different future.”

Joan Nixon, a veteran lesbian feminist activist and one of Lane’s closest friends, said, “Bettye was modest and shy. But as a photojournalist she was tough, fighting the big boys for the picture.”

Bettye Lane, at work with her camera, at a Lesbian Feminist Liberation meeting circa 1972. | PAULA A. GRANT

Author and activist Barbara Love, another very close friend, said, “She was always very feisty as a photographer. She got there early, knew where the best spots were and wouldn’t let anyone push her around.”

Columbus Circle — site of an art installation at the moment — was the scene of an Italian-American rally in 1971 at which mob boss Joe Colombo was a participant. Lane was a few feet from Colombo when he was shot in at the rally by a street hustler, and she got some very memorable photos. When Joey Gallo was shot and killed in Umberto’s in Little Italy a year later in retaliation for the Colombo shooting, Lane’s nephew Gary O’Neil remembers her dashing downtown from her apartment to cover the scene. She had to be where the action was.

The action in the New York Lane loved was in the streets — mass demonstrations for civil rights, May Day rallies against the war, the early actions of the militant gay and lesbian rights movement from Stonewall on, feminist marches (including the first Women’s Strike for Equality), and searing demonstrations protesting government inaction on AIDS. Lane was there for all of them.

“I loved protests when they were really protesting,” she once told me for an interview, “when they were there because they were not being heard. I photographed the human condition and the human spirit.”

She said, “It got quieter in the ‘90s.”

Because Lane got shots at actions that no one else did — such as the Stonewall Rebellion in 1969 — her work has been featured in scores of documentaries and books as well as in museums. One of her photos was included in the “Celebrate the Century” US Postal stamp series for 2000.

“She took meticulous care of her archives,” Love said. “Everything’s in boxes and labeled. She lived in an archive. She valued her work more than her life.”

O’Neil said her archive is in the process of being placed at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe, at Smith College, at the Rubenstein Library at Duke University, in Washington’s National Museum of Women in the Arts, and in the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn. “We will explore other avenues to preserve her work and legacy,” he said.

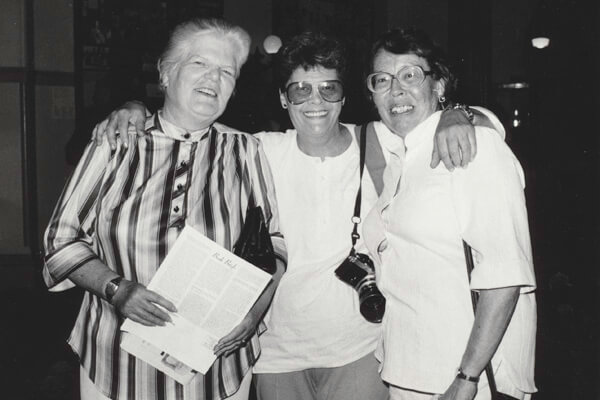

Bettye Lane standing between pioneering lesbian activists Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. | MORGAN GWENWALD/ COURTESY: LESBIAN HERSTORY ARCHIVES, MORGAN GWENWALD COLLECTION

Lane’s health problems ranged from stomach cancer to rheumatoid arthritis to skeletal problems, the latter probably due to “all the heavy equipment she had to carry,” Love said. “But she was very positive and private to the end.”

Lane got started in journalism at Harvard’s News Office and studied photography at Boston University. She said she bought her first Leica from Michael Rockefeller for $50. She went to New York to work for CBS in the early 1960s at a time when women were still strongly discriminated against. Her big break came while shooting a protest at the UN in 1966, where she met the photo editor of the National Observer, who took her work for years.

“I always got into the middle of a demonstration,” she told me. “There were sometimes four or five demos a day” in that era.

Lane’s devotion to the feminist movement meant “lugging her equipment to every rally — whether she was paid to go or not,” the New York Times reported. She became close to such feminist luminaries as Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, and Flo Kennedy.

Her family and friends also testified to her deep patriotism, having had two brothers who served in World War II and a father who came through Ellis Island. She was born Elizabeth Foti in 1930 of immigrant parents in Boston, the last of eight children in the Depression, leading her mother to put her into the care of a wealthier family for a time in order to survive, according to Nixon. In addition to her many nieces and nephews, she is survived by one sister, Josephine Caton of Boston

“She had no kids of her own and helped raise us,” O’Neil said. “And she didn’t lose her Boston roots.”

While she was briefly married to a man, Lane was mostly private about her own sexuality, becoming more open in her later years. “For a long time she did not identify as a lesbian photographer because she didn’t want to be marginalized,” Nixon said. “She more or less described herself as a feminist photographer or just a news photographer.”

There will be a memorial services for Bettye Lane at the Judson Memorial Church at 55 Washington Square South on Saturday, November 3 at 11 a.m.