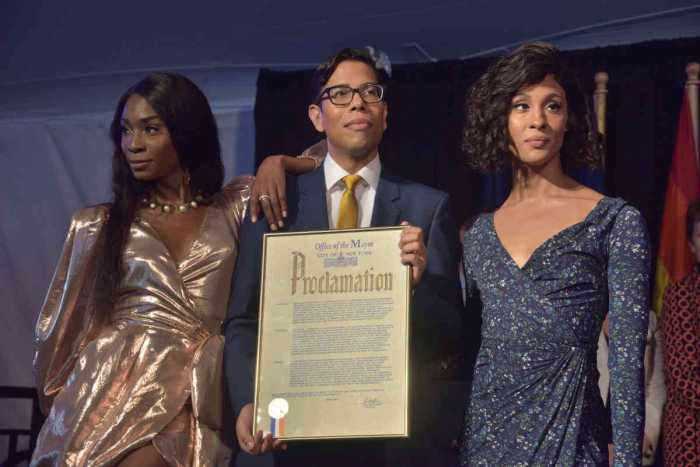

Actor Cynthia Nixon with First Lady Chirlane McCray and Mayor Bill de Blasio at Gracie Mansion on June 26. | ED REED/ MAYORAL PHOTOGRAPHY OFFICE

Mayor Bill de Blasio and his wife, Chirlane McCray, haven’t yet moved into Gracie Mansion, but they used the official mayoral home to play hosts to a diverse crowd of hundreds of LGBT New Yorkers and allies celebrating Pride the evening of June 26.

“This is what I call a rainbow,” McCray told the gathering.

Attendees sipped wine and feasted on roast chicken, burgers, hot dogs, and plenty of healthy options as they enjoyed sweeping views of the East River from the 18th century mansion’s expansive lawn. Unlike a garden party at Buckingham Palace where Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip mingle amidst the guests, de Blasio and McCray spoke to those assembled from a stage and slipped away afterwards without meeting guests other than the most high-powered, including City Council members and the mayor’s own commissioners.

The queen, of course, doesn’t generally have to worry about being confronted on political issues the way New York’s first couple does. Then again, Prince Philip is unlikely to talk about his sexual and romantic past as candidly as McCray –– to the evident delight of her husband –– did about her life as a young lesbian activist.

“I came to New York in 1977,” she said. “I wanted to write and, of course, I was looking for love.” She soon found friends who “introduced me to gay New York City.” McCray now holds the title of first lady, which appears on releases from the mayor’s office, but as I remember from my days in the gay movement of the mid-1970s, calling a woman a “lady” constituted fighting words, particularly in Salsa Soul Sisters, a group of lesbians of color McCray said “stamped my membership card ‘forever.’”

These are details that don’t always make it into the autobiographical reflections McCray includes in her speeches, though news of her 1979 Essence article about being a young, black lesbian surfaced early in her husband’s campaign through a nasty article in the New York Post that was followed by an outraged response from de Blasio. His willingness to stand up to the baiting brought what was then a flailing candidacy visibility, defining him as a different kind of politician, unembarrassed about his modern family.

“I know that if some of the pioneers of the gay movement could come back and see what happened, they would be so proud,” McCray said to a crowd that, in fact, included some of those pioneers, such as Steve Ashkinazy and Allen Roskoff, veterans of the early ‘70s Gay Activists Alliance.

Even though de Blasio handily beat out lesbian Christine Quinn for the LGBT vote in last year’s Democratic primary, the bulk of the community’s political establishment went with Quinn –– but was nevertheless welcomed to this party. Out labor leader Stuart Appelbaum, of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, one of Quinn’s point people on attacking de Blasio, was even given a shout out by the live-and-let-live mayor, as was Bill Thompson supporter Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers.

Early de Blasio supporters Christine Marinoni, who now works for the Department of Education, and her spouse Cynthia Nixon warmed up the crowd for the mayor. Marinoni said that when candidate de Blasio asked her to head up his women’s committee in 2012, “I said, ‘I’m a bulldagger, not a woman!’ But he knows that people aren’t only one thing. What we believe in can truly trump identity.”

De Blasio said when he met McCray while they both worked for Mayor David Dinkins, “there were violins playing, a thunderbolt hit me, I heard angels singing. I did not ask for her identification card! I just fell in love with her.”

He also talked about the most visible lesbians in his administration, citing Marinoni and saying, “I did not know we had a new title for Emma Wolfe: ‘Power Lesbian’ and subtitle, ‘Director of the Mayor’s Office of Intergovernmental Affairs.’”

In talking about his progress on LGBT and AIDS issues, de Blasio cited “more funding for runaway and homeless youth” and then, with indignation in his voice, said, “A lot of these kids have been put out of their own house by their own family, and that is unacceptable.”

He added, “I’ve spoken about this as a parent. I don’t understand any parent –– I don’t care what values they happen to have been brought up with –– I don’t understand any parent who would treat their own child that way instead of embracing them and loving them, and including them and respecting them. So sometimes we have to do it if a family won’t do it. We have to save those children and uplift those children.”

The mayor also touted the implementation of a 30 percent rent cap for people living with AIDS and receiving public assistance. On this issue, he said, many of those in the audience “never stopped organizing, and now it’s done.”

The legacy of Stonewall, de Blasio said, is a “spirit of not accepting exclusion, of not accepting second-class citizenship. That spirit has to be alive every single day until the mission is done.” He got a big hand when Nixon noted “he refuses to march in non-inclusive parades” such as on St. Patrick’s Day in Manhattan, though many in the crowd were among those who challenged him on continuing to allow city personnel to march in uniform at such discriminatory events.

The mayor concluded his remarks by saying, “We move forward together.” He succeeded in bringing a politically and socially diverse crowd together at Gracie Mansion, but he is likely aware he will continually face challenges in sustaining that sort of unity on the host of issues that face an even more diverse city.