Charlie Plummer in Andrew Haigh’s “Lean on Pete,” which opens April 6. | A24

Is there some special insight LGBTQ folks posses? In my most copasetic moments, I’ve thought this to be true. After all, being disenfranchised by the status quo offers one the possibility of a keener perspective on its workings than that enjoyed by those who aren’t obliged to question it in order to survive. Think of what Oscar Wilde, Noël Coward, and Gertrude Stein had to say about politics, family, romantic love, and language itself, much of it exceedingly pointed and incisive.

Not all queer people share this keener perspective, of course. Self-loathing homosexuals (one could scarcely call them “gay”) like Joe McCarthy henchman turned Donald Trump role model Roy Cohn and more recently alt-right would-be provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos are exceptions to the rule, with their overt hostility to the “out and proud.” On a less histrionic level so is writer-director Xavier Dolan, who recently declared, “I would not say that being gay has influenced any of my work. And will probably not. I’m gay, but I also have brown hair and I’m nearsighted.” Well so much the worse for him. Such verbal shallowness only serves to underscore his artistic shortcomings.

The same can’t be said of today’s most important proudly out gay filmmakers Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, Tom Kalin, and now, most remarkably, Andrew Haigh. Besides gayness, Haynes has dealt with everything from environmental illness (“Safe” in 1995) to the problems of the deaf (“Wonderstruck” in 2017).

With “Lean on Pete,” gay Brit filmmaker again shows nuanced insights into how lives are lived

While Van Sant explored the lives of gay street hustlers in “My Own Private Idaho” (1991) and memorialized a martyred gay rights pioneer Harvey Milk in “Milk” (2008), he has also dealt with a straight working-class mathematical genius in “Good Will Hunting” (1997) and, most recently, a paraplegic cartoonist in “Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot” (2018).

Kalin, by contrast, has dealt with gayness but only within extreme and problematic circumstances: in the Leopold and Loeb murder case biopic “Swoon” (1992) and in “Savage Grace” (2007), about the life and death of queer upper-class sybarite Anthony Baekeland and the incestuous-minded mother he murders. Not exactly something to make GLAAD glad — though fans of the iconoclastic New Queer Cinema have been delighted.

When it comes to Haigh, his departures from gay material are of a quieter and devastatingly subtler sort.

Born in 1974 (five years after Stonewall), this British writer director initially made his mark with three straightforwardly gay projects: “Greek Pete” (2009), a lightly satirical comedy about a rent boy, “Weekend” (2011), a deeply touching romance about a one-night stand that rapidly turns into something more; and last, but far from least, “Looking” (2014-2016), the HBO series about a group of gay friends in modern day San Francisco. All three films exhibit an ability to deal with gay lives and loves honestly, without sensationalism, and often movingly.

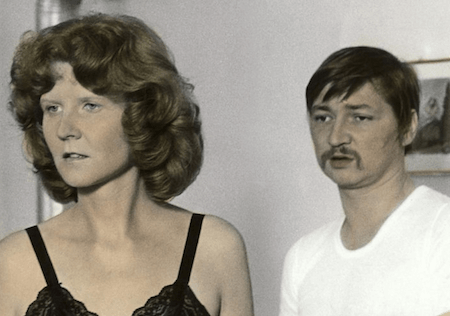

From there, Haigh has taken off with great success in very different, quite unexpected directions. “45 Years” (2015), an adaptation of David Constantine’s short story “In Another Country,” deals with a long-married, middle-aged straight couple and the upset caused when a nearly-forgotten episode from their past rises up to reconfigure what they had thought was a calm and unperturbed life. Evidencing the same sensitivity toward the ebb and flow of personal feelings put so movingly on display with unknown actors in “Weekend,” “45 Years” stars British film icons Charlotte Rampling and Tom Courtenay. Again, one cannot help but be deeply impressed by Haigh’s ease with realistic drama (he has cited the Karel Reisz’ 1960 classic “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” as a major influence) and also the mastery with which he guides stars with many more years in the film business.

Throughout “45 Years,” one can sense Haigh’s genuine curiosity about the warp and woof of a relationship utterly different from the ones he has known, yet at the same time relevant to him in that what these characters experience in coupled maturity may well await Haigh in his own life with the man he recently married.

But “45 Years” is only a sight detour compared to Haigh’s most recent film, “Lean On Pete.” Adapted from a novel by Willy Vlautin, it centers on Charley, a sweet-spirited teenager (played with exceptional grace by Charlie Plummer), who, following the death of his father (his mother was out of the picture many ears before), must fend for himself with naught in the way of resources. He finds himself teaming up with a horse trainer (the ever-resourceful Steve Buscemi) who, with the help of a female jockey played by Chloë Sevigny, races horse at small-time events in the Pacific northwest. Put in charge of a horse named Lean on Pete, Charley finds himself emotionally drawn to the animal, even though both owner and jockey keep telling him “he’s just a horse.” This, of course, signals tragedy as horses like Lean on Pete, once their racing prowess has ebbed, are “sent to Mexico” — meaning meat processing plants for dog food. Foolhardy Charley, realizing Lean on Pete’s time is at an end, kidnaps the horse and sets off on a journey that seems aimless at first, but is eventually aimed at reuniting the boy with an aunt he hasn’t seen in years.

Foreign-born filmmakers like Michelangelo Antonioni with “Zabriskie Point” (1970) and Emir Kusterica with “Arizona Dream” (1993) seem keen to portray America — particularly the west — as a kind of surreal wonderland. But being British, Haigh fits right into America just like Tony Richardson did with “The Border” (1982) and “Blue Sky” (released posthumously in 1994, three years after his death from AIDS) and Karel Reisz with his Patsy Cline biopic “Sweet Dreams” (1985).

What makes Haigh’s film come alive is the simplest thing imaginable — the sight and sound of his hero walking with and talking to the horse he’s come to love. No, this isn’t a “kid loves horse” story like “National Velvet” (1944) or “The Black Stallion” (1979) for Haigh makes clear that what Charley is engaged in in these scenes is a species of interior monologue. He’s a young man in crisis trying his best to hold himself together while holding out hope that something will save him. He is in the end saved, being reunited with his aunt, but the interior monologues he’s been engaged in are at an end, since Lean on Pete was indeed “just a horse.”

Haigh’s embrace of the sadness and disappointment life, too, is refreshing, as is the fact that this is a film about an adolescent male without anything related to sexuality in it at all. We often forget that that’s not the only thing involved in growing up and “Lean on Pete” is a starkly sensible reminder of this fact.

At present, Haigh is in the midst of making “The North Water,” a five-part television mini-series scheduled for release in 2019 about a former army surgeon who signs up as a doctor aboard ship making an expedition to the Arctic only to discover that one member of the crew is a dangerous psychopath. No telling at this point if there’s anything gay in this story. But whether there is or isn’t, one can be sure it will be redolent with the emotional insight that makes Andrew Haigh one of today’s most important filmmaking talents. His body of work offers further proof that gayness may well be an artistic advantage for those who truly know who they are and what life in all its complexity is really like.

LEAN ON PETE | Directed by Andrew Haigh | A24 | Opens Apr. 6 | Angelika Film Center, 18 W. Houston at Mercer St.; angelikafilmcenter.com/nyc | Paris Theatre, 4 W. 58th St.; theparistheatre.com