George Butler looks at John Kerry’s time in Vietnam and as an anti-war activist

Forty years ago, two young guys who had heard about one another through mutual friends came face to face at a college party in Manchester, Massachusetts.

“We shook hands,” Georege Butler recalled recently, “and with that shake of the hands I felt this man was someday going to be president.”

Of the United States, that is. John Kerry was already president of the Yale Political Union.

“For credibility,” Butler continued, “when I shook hands with Arnold Schwarzenegger at a Mr. America contest at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1972––I was there covering it for Howard Smith’s column in the Village Voice––I thought Schwarzenegger was someday going to be governor of California.”

Five years later, moviemaker Butler’s surprise smash-hit documentary “Pumping Iron” would––as it were, by accident––have a good deal to do with propelling the Austrian strong boy into the American cultural stratosphere.

Will Butler’s new documentary, “Going Upriver: The Long War of John Kerry,” play a part in propelling into the White House the major party candidate who did serve his country in Vietnam?

We may never know, even if Kerry wins, but it’s not irrelevant that the unapologetic, 92-minute film underscoring his courage under fire in the Mekong Delta, and no less courage thereafter as a Vietnam veteran against the war, opened nationally one month and one day before election day 2004.

The Upper East Side of Manhattan, his home away from his farm in Holderness, New Hampshire, is where we found George Butler on a morning a few days before the film’s launch.

Butler was asked what, at that 1964 encounter, made him think this 21-year-old could someday be president? (Kerry was born December 11, 1943, just two months after Butler.)

“He had stature and bearing. A very compelling man. There was also an aura about him. He was a great athlete. He’s played soccer with two of my friends. He was fun to be with.”

Did he drink? Did he party? Any of those things?

“He did everything.”

Did Kerry himself know he might someday be a possible president?

“I think it crossed his mind.”

Kerry had been at Yale. Butler had a B.A. in classics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“We kept in touch. We were at a friend’s wedding in Chicago the weekend before Kerry went into the Navy. He had to leave the wedding early.”

Had the Butler of those days any idea of making movies?

“Zero.”

The 1972 assignment from the Voice to cover the Mr. America contest at BAM flowered into a 1973 “Pumping Iron” book for Doubleday,

“Then in 1973 I made a test film with Arnold. I screened it for 100 potential investors. At the end of the screening, Romulus Linney [the American playwright and father of actress Laura Linney] stood up and said: ‘George, I speak for every investor in this room. If you ever make a movie about Arnold Schwarzenegger, you’ll be laughed off 42nd Street.’”

Two years later, Butler decided he would make it anyway.

“I asked Howard Smith [who had made a hit called ‘Marjoe’] to direct it. He refused. I got some money, flew to California, picked up a crew, shot Arnold in a body-building contest, flew back to New York, and hired an editing room at the Maysles brothers’ studio.

“Next door, Emile de Antonio was making a movie about the Weathermen, very secretly, because the FBI was hot on their heels. One Saturday morning my assistant called and said: ‘George, it’s gone’—all our footage. The FBI had stolen it.”

With a big smile, Butler said, “Can’t you just see J. Edgar Hoover sitting down with [top aide and lover] Clyde Tolson, and instead of [Weathermen member] Bernadine Dohrn, in comes Arnold Schwarzenegger?”

Back to John Kerry.

“In late ’69, he called me up, wanted me to come to Boston. Said he was going to run for Congress against Father Robert Drinan in the 3rd Massachusetts District, and would I handle press relations? I did that. There was no campaign photographer, so I started taking pictures.”

Why would John Kerry want to run against a good liberal such as Drinan?

Something of a pause, then: “Because he had been in Vietnam and Drinan hadn’t. Because it was John’s idea to be the first Vietnam veteran in Congress. But they were two good men.”

Kerry lost, which was a real shock to the man who had become the nation’s most famous Vietnam veteran.

“You know,” Butler said, “I’ve always walked a line, always been in this odd position of being a friend of Kerry’s and documenting him and working for him.”

Which brought us to “Going Upriver”––how had that project come into Butler’s head?

“It’s sort of always been there,” said British-born Butler, raised in the U.S. from the age of 14. “In 2002, I suspected that he was running for president. I started a film in 2003, a different film, more of a campaign film. Then Kerry ran out of steam and I subsequently ran out of money.

“Then I changed the idea of the film. It was to be about Vietnam and the peace movement.”

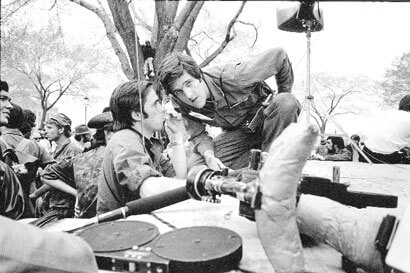

That is what the final movie essentially has remained, with intensity, drawn in considerable part from network footage of the five-day April 1971 occupation of the Mall in Washington by Vietnam Veterans Against the War. It was during that occupation that the protesting veterans threw their ribbons and medals over a barricade onto the Capitol steps and 27-year-old John Kerry’s offered powerful and moving testimony before the William Fulbright’s Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Kerry’s testimony is the high moment of the film, and was in important ways the American body politics’s high moment that year, that era even. Would that John Kerry had that passion and that clarity as candidate for president in 2004. Instead of all the hero stuff or the Swift Boat stuff, pro and con, 90 seconds of the heart of that testimony would make powerful campaign commercial.

Butler leaned back, spreading his arms and hands wide.

“I don’t disagree,” he said. Having recast the tenor of the film, he “started all over again in April 2004 and made it in four months.”

Kerry, amidst those five high-pressure 1971 days and nights in D.C., got little or no sleep the night before he went before the Senate committee. Did he actually write that statement himself?

“Absolutely. He consulted with [onetime Robert F. Kennedy aide] Adam Walinsky, but Adam did not write the speech. It was a speech John had been working on for about six months.”

George Butler was born in Chester, England, an old Roman town on the Welsh border near Liverpool. His mother was Dorothy West, a Bostonian, his father was Major Desmond Butler of the Royal Welch Fusiliers––”that’s Welch with a ‘c,’ a very literary regiment, it was [World War I poet] Siegfried Sassoon’s regiment.”

George grew up in Wales, Somalia, Kenya and Jamaica. At 14, was sent to America to go to Groton. After Chapel Hill, he earnd an M.A. in creative writing from Virginia’s Hollins College. In addition to “Pumping Iron,” he has written “The New Soldier,” and, now, “John Kerry: A Portrait,” an album of photos. His films include a triptych based on “The Endurance,” the best-seller about Antarctic explorer Ernest H. Shackleton by Carolyn Alexander, with whom Butler shares the New Hampshire farm.

Speaking of Kerry’s family, Butler emphasized that the candidate has not always known the full story of his background.

“His father’s parents were Jews who emigrated to America from Vienna in 1904. His grandfather had changed his name from, I believe, Kohn. He became Kerry, and he committed suicide in 1922. I read this in the Boston Globe in February of this year. At my house in New Hampshire, John on one or two occasions mentioned he had some Jewish heritage, but he certainly didn’t know that his grandfather had committed suicide.”

What does Butler think are John Kerry’s chances on November 2?

“Excellent. He’s great in the stretch. I’ve seen him come from behind six times––six in a row. The [1996] general election for the Senate against William Weld was exactly like this, and Weld was the same kind of Republican as Bush, relatively speaking.”

What’s next for Butler?

“I’m going to make my next movie. Have three coming up in a row. An Imax about the Rovers on Mars, an Imax about gorillas in the Congo, and a film about Bobby Bowden, the Zeus of the South. He’s the coach at Florida State, and this is going to be a movie about football and religion.”

Butler was offered the suggestion that religion is one of the main things wrong with the world today.

“I agree,” Butler responded. “Religion of the Bush sort”––the kind where you bring God onto your side.

Viewers of “Going Upriver” won’t easily forget images of the burning eyes of veteran after veteran back from Vietnam, whatever their beliefs, God or no God. God doesn’t help much when you’re up the river without a paddle. You have to do it yourself.