Peter Krause, Michael Mayer salvage a wearying Arthur Miller exercise

In “After the Fall,” Arthur Miller writes about two of his favorite topics—egoism and sex. He wraps these subjects in a heavy-handed, even if partially obscured, metaphor that attempts to recast original sin—Man’s separation from God—as original selfishness—Man’s separation from what he wants, which is, more often than not in Miller’s world, sex.

By today’s standards, it’s a tired theme, but one which clearly had a grip on Miller—he returned to it ten years after the 1962 debut of “After the Fall” in “The Creation of the World and Other Business” (a clumsy quasi-comedy about the Garden of Eden interpreted for contemporary sensibilities) and a scant four years ago in “The Ride Down Mt. Morgan.”

These plays are alternately laden with the more overwrought purple hues of “drama” or straining toward comedy. Both of these tendencies plant Miller’s work solidly in the middle of the last century, making it dated and remote. Nonetheless, Miller is a “Great American Playwright,” and justifying extra-marital sex is a great American theme, so when one of his older plays is dusted off, attention, as they say, must be paid.

On the page, “After the Fall” is dense, full of self-indulgence and navel gazing from the central character, Quentin, and overlapping short scenes taking place at different times—a way of exploring the chaos of Quentin’s experience. This may have been a novelty 42 years ago, but it is a commonplace dramatic structure today. And of course adultery, even when a “star” is involved—yes, think Marilyn no matter what anyone says—is not even remotely shocking. It’s barely venal and certainly not a cause for two-and-a-half hours of minute examination. The characters are either so completely self-involved—whether or not mentally ill—or so sketchy that it’s a wonder the whole play isn’t simply a series of monologues.

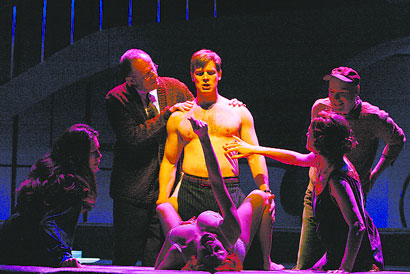

Given all of this, it’s remarkable that the Roundabout’s production is so engaging and, rather than being a soporific cultural event that’s putatively “good for you,” instead overcomes the weaknesses of the play to deliver surprisingly effective theater. Director Michael Mayer has trimmed the text of some of its more plodding speeches, assembled a terrific cast and generally uses a very deft hand to give the world of the play a much-needed buoyancy. He has created a balance among the characters that allows them all to be dysfunctional rather than focusing exclusively on Quentin and his guilt, which would be stultifying. Central to the show’s success are the performances by the three main characters. As Quentin, Peter Krause does an extraordinary job of making the character a man rather than a literary device. He is a careful, specific actor who works with quiet integrity to wrestle a believable man from what has been written. Quentin is not dramatic; he is an ordinary man caught between his higher sense of himself and his lower desires, and the subtlety of Krause’s performance gives it extraordinary warmth and grace. In choosing between truth and fireworks, Krause consistently chooses the former so that when he is roused to passion it is both understandable and shocking, the outgrowth of internal tension that even in lighter moments is always there.

Quite the opposite is Carla Gugino as Maggie. She swings for the bleachers with every scene as she travels from dim receptionist to major star, and yet from the beginning she makes us uneasy—as though the neurotic she always was has been waiting for the chance to be released. Her emotional and physical chaos provide a wonderful counterpoint to the contained and simmering Quentin, and it’s clear they are both trapped in lives of their own design.

Equally trapped is the persistently affronted and angry Louise, Quentin’s wife when he meets Maggie. Miller hasn’t given Louise much to do other than be angry and affronted—to be a foil to Maggie—but Hecht has a terrific presence and acquits herself very well.

The rest of the characters serve as plot devices, but they are all consummate professionals. Particularly good are Candy Buckley as Quentin’s mother, Mark Nelson as Lou, Quentin’s friend and one of his honorable if quixotic projects, and Jonathan Walker as the square, preppy and amoral Mickey.

Though the play was written to be performed in a black box, designer Richard Hoover has gone one better. He has adapted Eero Saarinen’s 1962 design for the TWA terminal at Kennedy Airport. It is a masterful set that gives Mayer and his cast ample opportunities for staging; there is nothing more inhuman even while crowded with people than the modern airline terminal. Saarinen’s attempt to add some kind of grandeur to a bleak experience is an apt metaphor and Hoover’s adaptation adds greatly to the production while reminding us that we have only fallen further despite our grand designs.

Ultimately, this is a very strong production of a tired play. Some of the devices—seeing to equate a bad relationship with a concentration camp—are laid on with a trowel, and some greater cutting wouldn’t hurt, but Mayer and Krause manage to keep the focus on the humanity of the characters, which counteracts Arthur Miller’s penchant for grandiosity, keeping this production consistently interesting, if not inspiring.