“The Method School thinks the emotion is the art. It isn’t. All emotion isn’t sublime. The theater isn’t reality. If you want reality, go to the morgue. The theater is human behavior that is effective and interesting.”

So said Agnes Moorehead, who may have created more effective, interesting characters on film than anyone, which is why my annual awards for best live performances are named for her. This year’s 10 Aggies go to:

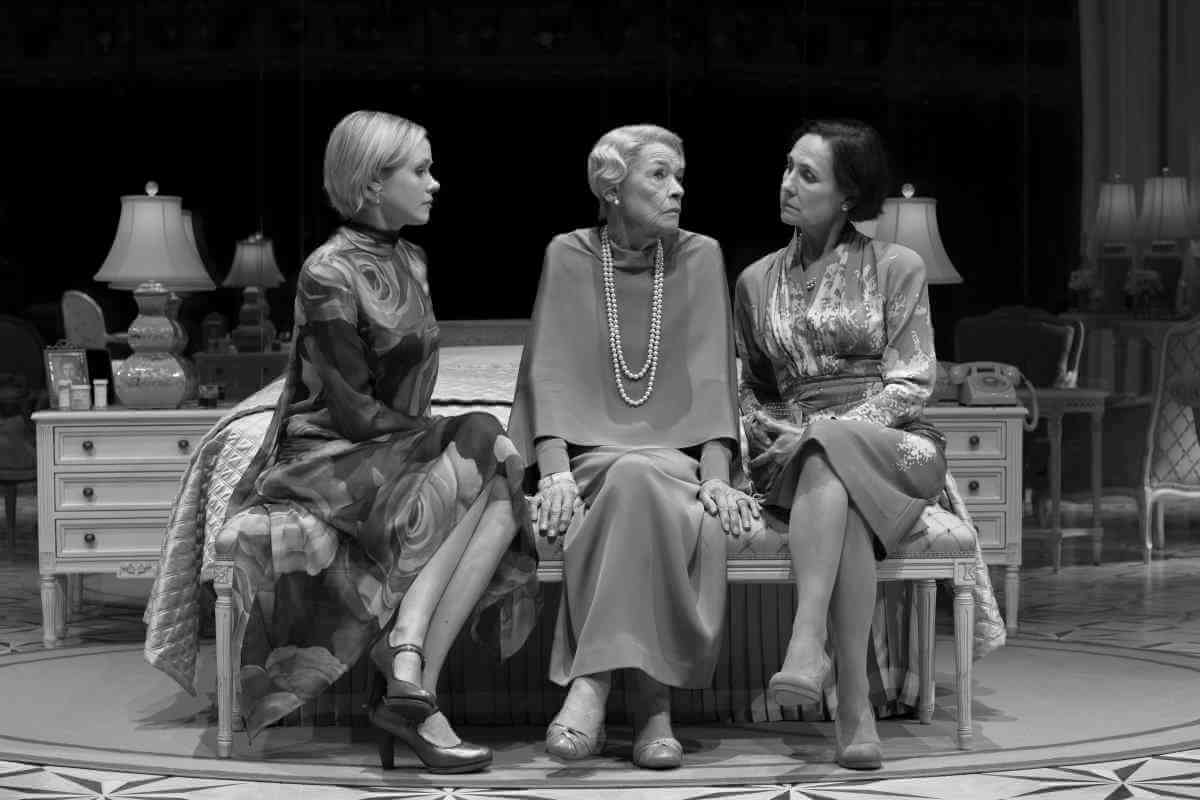

“Three Tall Women”

When this spectacular revival of Edward Albee’s mesmerizing three-hander ended, I felt almost in a state of grace, as one does in the rare instances of truly great theater, barely able to move or bear the banal chatter of the enthralled, exiting audience. In the best costumes of the season (Ann Roth, of course), Alison Pill finally showed me why she is so ubiquitously cast, obviously rising to the magnificent occasion of sharing a stage with those titanesses Laurie Metcalf and a still ferocious Glenda Jackson. I’d forgotten how much I’d missed Jackson’s monumentally commanding voice.

“The Ferryman”

After so many impoverished-seeming, paltry American family sagas, usually set around a dining table in some upscale country retreat, the sheer opulence of this play’s huge, roiling, cross-generational cast, imported from the UK, easily riveted its audience. Although not a great play, crafted from shards of Se án O’Casey, Liam O’Flaherty, “Of Mice and Men,” and Lord knows what else, it definitely works, and Sam Mendes, back in blazingly theatrical form made it a full, rich, and finally shocking evening of pure entertainment.

“My Fair Lady”

Many had issues with Bartlett Sher’s feminist rethinking of what some consider the greatest of musicals. I had little problem with him wanting to emphasize a flower girl’s self-empowerment, especially after delivering the rest of this gold standard show with so much real elegance and loving care. Even a highly mixed cast — never less than adequate but few achieving the sublime — could not take away from the work’s enduring brilliance or Lauren Ambrose’s detailed, startlingly authentic, beautifully sung portrayal of Eliza.

“Lobby Hero”

Acted with piercing humanity by Michael Cera and Bel Powley, Kenneth Lonergan’s affecting urban chamber piece emerged as a true repertory classic, with its deep humanity and sage observation of regular Joes searching for transcendence. Trip Cullman’s direction was all the more treasurable for its gracefully timed unobtrusiveness.

“Saint Joan”

The French warrior girl may have a great story, but rarely has it been dramatized effectively, whether it was the too-glossy Ingrid Bergman 1948 film “Joan of Arc” or the God-awful David Byrne musical “Joan of Arc: Into the Fire,” foisted on the Public Theater last year. George Bernard Shaw’s play, written in 1923, has always struck me as some kind of definitive take on her, but rarely revived because of the costly large cast and spectacle it requires. Roundabout did a very decent job of it, keeping the action clear and ever-propulsive, ploughing through Shaw’s challenging verbosity. It never once came across as too philosophically dry, thanks to the luminous presence in the title role of Condola Rashad, a daring casting choice. She paid off, delivering a performance that verged on greatness. It’s damned difficult to convey saintliness convincingly on the stage without seeming a sanctimonious freak, blowhard, or tiresome goody-goody. She quietly but fervently owned the role, played it like a simple country girl radiantly touched by her private God as well as destiny, and, indeed, was great.

“Carousel”

I’m sure this wasn’t the first revival of the estimable Rodgers and Hammerstein musical in which the comic secondary leads, playing Carrie Pipperidge and Enoch Snow, stole the show from the tragic central couple of Billy Bigelow and Julie Jordan. But Alex Gemignani and, especially, Lindsay Mendez, whose performance automatically entered the realm of the legendary, had such true chemistry, individually and together, that they were easily the most romantic couple on a New York stage in all of 2018. Jessie Mueller and Joshua Henry essayed Julie and Bigelow, with their acting even taking precedence over their singing: his searingly realistic death and her heartbreaking discovery of him, bloodied and finally bowed, tore at your heartstrings. Justin Peck’s choreography was the most exciting of the season, and, as always, Ann Roth’s vivid costumes told each character’s entire backstory from their very first entrance.

“Conflict”

Miles Malleson (1888-1969) was a British character actor best known for the films “The Importance of Being Earnest,” as Dr. Chasuble, and the clueless, toy-loving, doomed Sultan in “The Thief of Bagdad.” He was also a skilled and very forward thinking playwright, whose “Yours Unfaithfully” (1933) dealt with open marriage, something he himself had with one of his three wives. The essential Mint Theater revived that play last year and this year briskly mounted hs “Conflict”(1925), filmed in 1931 as “The Woman Between.” It was a gripping account of a love triangle set against a particularly trenchant political background, superbly directed by Jenn Thompson and acted with superb relish by a sterling cast.

“Miss You Like Hell”

Ever since she illuminated the stage in the epochal “Rent,” I’ve been waiting for a play to truly showcase the special wonder that is Daphne Rubin-Vega. She found one in this utterly disarming, timely, and deeply moving musical (book and lyrics by Quiara Alegría Hudes; music and lyrics by Erin McKeown), featuring a funky road trip taken by an immigrant Mexican mother (Rubin-Vega) fearing deportation and her estranged, resentful, and possibly suicidal daughter (Gizel Jiménez). They encounter a retired gay couple (David Patrick Kelly and Michael Mulheren), quirky yet possessed of a near magical charm, and when I spoke to Rubin-Vega about it, she enthused, “I loved doing that show. We just recorded the cast album, and Gizel was a phenomenal find, the real thing!”

“Smokey Joe’s Cafe.”

Some may have turned up their nose at this jukebox revival, but a tirelessly talented cast put it over with verve and a joyously irresistible commitment which made it one of 2018’s most entertaining. Although the sexy, triple threat guys nearly broke their backs selling those infernally catchy Stoller-Lieber oldies, and Alysha Umphress’ pipes could knock the tiara off Miss Liberty, Nicole Vanessa Ortiz definitely emerged as a very special star in her own right, bringing down the house each night with “Hound Dog” and “Fools Fall in Love.” This Apollo Theater Amateur Night and “Apollo Live” multiple winner simply has one of the great voices of our time to be heard, anywhere. I was lucky enough to be present at her New York theatrical debut, when she filled in as understudy for a gal in “Spamilton.” As nice as she is talented, she never lets me forget that I wrote the very first review she ever got and I hope to rave about her lots more in the future when she rightfully assumes the big musical roles she was born for.

Kathleen Turner at the Cafe Carlyle

It’s always thrilling to be there at the moment a Star becomes a Legend. We are talking Kathleen Turner, who made her breathtaking Café Carlyle cabaret debut earlier this year. One of the top 10 such shows I have ever seen, Turner truly crowned her long career with this event. Utterly assured and comfy in her skin, I doubt if anyone since Mabel Mercer has ever commanded a room with such royal panache, holding us in the palm of her hand, with a surprisingly rich Zarah Leander baritone (crooning her favorites from the Great American Songbok, which are our faves, as well), so naturally musical, pitch perfect, and seasoned, she almost made Dietrich sound like Billie Burke. And, as raconteur and political commentator, Turner was pretty damn peerless, her every dry and/ or humane observation delivered with the crack timing of a born farceur. It was her version of “Elaine Stritch: At Liberty,” but unlike Stritchie, she did not have John Lahr or George C. Wolfe tweaking her life story. It was all her and quite, quite wonderful.

I shamefully confess that I had no idea Dance magazine, beloved by so many of us, was still in publication in these dire days for print, when magazines like the venerable Film Journal, which started me on my writing career in the 1980s and where I continued to write, are closing shop at an alarming rate. But Dance continues, thank Terpsichore, and its awards presentation on December 3 was one holy night.

Misty Copeland introduced the evening and was gratifyingly vociferous about the responsibility and honor of being, as she said, “black, a black woman and a black ballerina.” The utterly magnificent Ronald K. Brown gave the most amazing extemporaneous speech that charted his gloriously wayward early career, harking back to his childhood and becoming a choreographer at the tender age of 18.

The presence of so many honorees of color, especially women like Copeland and Lourdes Lopez ,who proudly crowed that she is the first Latina to ever head a major dance company (Miami City Ballet), made the warmly familial celebration even more special.

The highlight of the night was a jaw-droppingly brilliant kinetic duet of a dance, “The Other You,” by virtuosos Andrew Murdock and Michael Gross of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago. It was splendidly choreographed by Crystal Pite (for her Kidd Pivot company), fusing modern, funk, mime, and barely controlled wildness to depict the difficulties of a relationship.