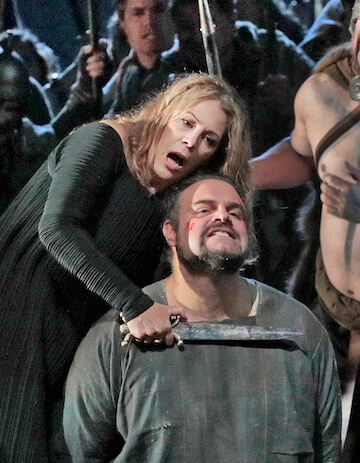

Jonas Kaufmann sings the title role in the Met Opera’s new production of “Werther.” | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Massenet’s “Werther,” an intimate music drama focused on interior emotion rather than overt action, has never been a natural fit for the grandiose Metropolitan Opera House. Audiences haven’t flocked to it despite the presence of many distinguished singers over the decades. Usually it is mounted as a vehicle for a superstar tenor divo (hopefully in tandem with a diva mezzo or soprano), as in the 1894 Met premiere starring matinée idol Jean de Reszke and the revival in 1971 with heroic Italian heartthrob Franco Corelli. With its one-note, melancholic, suicidal hero, unconsummated romance, somber tone, and lack of dramatic action, “Werther” has remained more of a succès d’estime than a crowd pleaser.

The Met unveiled a new “Werther” on February 18 as a vehicle for superstar German tenor Jonas Kaufmann, staged by Richard Eyre (following his successful Met “Carmen”). The Met originally cast diva Elina GaranÄa as Charlotte, but her pregnancy made way for the Met debut of distinguished French mezzo Sophie Koch. Eyre and the designer Rob Howell update the action to around 1910, which doesn’t add anything but does no harm since provincial European mores changed little over the two centuries that elapsed.

The production’s visual style is an uneasy mix of stylization — tilted architectural frames and heightened perspectives — and well-stuffed, artfully detailed period realism reminiscent of “Downton Abbey” or Merchant-Ivory films. Eyre attempts to compensate for the lack of action in the first two acts by adding projections onto the front scrim and mimed tableaux during orchestral preludes and interludes. Before the first act even begins, we see the death of Charlotte’s mother, her funeral. and a montage of ravens flocking on tree branches that looks like an outtake from an animated Tim Burton reboot of “The Birds.”

Jonas Kaufmann proves himself a star in new Met Opera “Werther”

Overkill is mixed with sentimentality — a quality shared by Alain Antinoglu’s slow, detailed but ponderously loud conducting. In the more dramatically concentrated third and fourth acts, Eyre minimizes the fussy cinematic flourishes and sharpens the focus on the principals — which is a good thing.

This is a distinguished cast, though Koch is the only authentic French stylist. The light, pointed brilliance and spring-like freshness of Lisette Oropesa’s coloratura soprano embodies the high-spirits of little sister Sophie. Oropesa’s Sophie acutely perceives the suffering in her family and is earnestly trying to counteract it. Serbian baritone David Bižić debuted as Albert, displaying warm tone and good French diction. Bižic’s smooth, earthy baritone effectively contrasts the grounded, virile military man with the moody, fatalistic Werther. Veteran Jonathan Summers sounds overly crusty as the Bailli but is energetic.

Koch’s plangent medium-weight mezzo-soprano, native diction, tall slender figure, and thoughtful facial expressions all contribute to a positive initial impression. However, her timbre has a generic, opaque color that dilutes emotional engagement. The high climaxes in Charlotte’s third act monologues emerged with congested strained tone. Koch’s interpretation of Charlotte as an emotionally repressed woman teetering on the brink seemed studied, lacking in spontaneity, the emotions applied to the surface instead of arising internally.

Kaufmann’s acting, in contrast, comes across as spontaneously lived in the moment. His darkly brooding good looks, long tousled curls, and slender, lithe frame enhanced by a long black coat and white scarf are the ideal visual embodiment of a tormented romantic hero. Kaufmann’s voice, though, with its idiosyncratic darkened, backward production, is not a natural fit for French opera. French-style tenors favor a bright, forward, narrow placement fixed high in the facial cavities emphasizing softly floated head tone (voix-mixte) in the upper register. Kaufmann’s sound is open-throated but covered. With iron control, he shifts from darkly smoldering baritonal sounds to backwardly crooned pianos and then in the emotional outbursts will take the lid off the voice for heroic high notes — suggestive of the mood swings of a manic depressive. He resembles a mini-Jon Vickers — with similar incipient mannerisms but also the same mixture of intellectual calculation and unbridled emotional intensity. Kaufmann’s spinto tenor sounds no more authentically French than the volcanically Italianate Corelli’s but vividly evokes an angst-ridden depressive with a death wish. He carries the production as a star should.

The fourth act is played in a tiny spare room placed downstage. Kaufmann’s death scene displays masterful control of vocal half-tints and inspires Koch to real eloquence — less really is more and the audience is drawn into their heartbreaking private world. Would that we had spent more time there earlier.

Two days later Jonas Kaufmann made his Carnegie Hall recital debut in a program devoted to German lieder. Helmut Deutsch on the piano accompanied him with authority. The heartbroken poet protagonist of Schumann’s song cycle “Dichterliebe” (“Poet’s Love”) is a kind of first cousin to Goethe’s sorrowful Werther. (I prefer a dark baritone or bass in the great German lieder cycles like “Winterreise,” but a lyric tenor better suggests the boyish yearning and vulnerability in Schubert’s “Die schöne Müllerin”).

I found that Kaufmann’s “Dichterliebe” lacked both the dark despair of a baritone and the yearning sweetness of a Wunderlich-type lyric tenor. He seemed to strike a middle-ground that was neither here nor there. In this and the earlier Schumann group from “Zwölf Gedichte,” he was impressive rather than personal or moving.

Wagner’s “Wesendonck Lieder” took Kaufmann into a more operatic sphere where he seemed totally at home. The smoldering, covered half tones suggested suppressed forbidden sensual longing that erupted into heroic tones of existential despair –– a preview of a future Tristan? (Wagner’s song cycle is a sketch for the later opera).

Franz Liszt’s “Tre sonetti di Petrarca” is a tricky cycle that mixes Italianate grand opera heroics with the anguished subtlety of German lied spiced with Hungarian harmonies. Kaufmann effortlessly switched gears vocally and interpretively, making the music his own.

Kaufmann then wowed the enthusiastic audience with a generous group of encores of Richard Strauss lieder (the tenor’s favorite composer but one who favors the soprano and baritone voice over the tenor). His renditions of Strauss’s “Freundliche Vision” and Schumann’s “Mondnacht” displayed open floated head tones in the upper middle register that he needs to utilize more of as Massenet’s Werther.

For his final encore, Kaufmann seduced the audience with an exuberant rendition of Lehar’s “Girls were Made to Love and Kiss” from “Paganini” (sung auf deutsch, but the second verse in English) warming them up for their re-entry into the bitter cold winter night.

The Met Live in HD presentation (metoperafamily.org/hdlive) of “Werther” is scheduled for Saturday, March 15 at 12:55 p.m. at various local venues. The HD cameras will bring you up close and personal with Kaufmann, enhancing the intimacy and emotional focus.