New York was awash in rainbows as it is every June, but this time there was a special meaning: the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, which ushered in the modern LGBTQ civil rights era. New York’s WorldPride is the first time the event, originating in Rome as a challenge to the Vatican’s power over LGBTQ rights issues in the year 2000, had ever been held in the US. According to the organizers, around 150,000 people participated in the main march, with about 7,000 each day at the Pride Island entertainment event.

While complete statistics were not fully available at press time, several million viewed the march, and it might have been the single largest one-day event in New York history. According to a Facebook post by Matthew McMorrow, an out gay top aide to Mayor Bill de Blasio, the march ran for 12 hours and 32 minutes, beating by nearly three hours its previous record.

The choice of grand marshals played homage to the history of the movement with Gay Liberation Front, one of the first gay rights groups, among them. Others included the Trevor Project, the cast of the transgender TV phenomenon “Pose,” UK Black Pride co-founder Phyllis Akua Opoku-Gyimah, better known as Lady Phyll, and Monica Helms, creator of the Transgender Pride Flag.

While in many ways a celebration of how far New York and the world have come on LGBTQ issues, many participating in the parade wanted to ensure that the need for further progress was not overlooked. And that included those symbolically leading it. At a press conference in the Empire State Building, one of New York’s most recognizable and visited landmarks, Indya Moore, who plays Angel in “Pose,” gave a moving speech about police brutality, the difficult bargain in corporate sponsorship, trans identity, and the LGBTQ movement’s disregard for issues affecting marginalized communities.

“When I see the police in the streets, I think about when I was in foster care, I was beaten and I had my hair ripped out of my head by a young cis girl, and I was arrested for it. Twice. Because she told the police I was a man,” Moore said. “I remember crying in that room, very scared. And I remember thinking about what happened to Sandra Bland and thinking that would happen to me.”

Moore continued, “I am wondering: Why they are there? Are they there to protect us or are they there to police us? Maybe they are there to make sure we don’t riot again.” Asking that Heritage of Pride, the group that produces the parade, consider hiring an outside security firm rather than police, she added, “So many of us don’t feel safe, even when there are rainbows painted on their cars. It feels like a mockery, when I think about my friend Layleen,” referring to Layleen Xtravaganza Cubilette-Polanco, a transgender woman who died on Rikers Island while placed in “restrictive housing,” which involves 17 hours each day in isolation.

Moore was also critical of the largely white power structure in many LGBTQ organizations, reminding those in the audience that “our blackness and our brownness isn’t included in those voices to liberate,” particularly admonishing the Human Rights Campaign. They also called on T-Mobile, one of the main sponsors of Pride, to provide more help to grassroots organizations that help trans women, including those who are sex workers.

Later that evening, the Empire State Building would be awash with rainbows, along with many other New York City structures, including the World Trade Center and Madison Square Garden.

This year’s parade was also structured to mix activists marching in contingents woven through with corporate sponsors. In some ways, this seemed a response to arguments the parade had become too commercialized, which is why an alternative parade, Reclaim Pride’s Queer Liberation March, was held earlier in the day along the parade’s 1970 route.

Corporations did indeed make for a huge part of the parade, from Facebook to Disney and ABC, which was broadcasting the parade, to a variety of airlines and other travel companies, banks, and others.

In keeping with the theme of WorldPride, this year’s was one of the most international Prides ever held in New York, a city already known for its diversity. Previous and future WorldPride host cities and organizations were among the first of the groups to set off during the march, from Italian groups like Circolo Di Cultura Mario Mieli, the event’s first hosts. Along with Rome, Madrid, Toronto, and London, all cities that previously hosted WorldPride, marched, in addition to Copenhagen Pride, where WorldPride will take place in 2021.

One foreign delight that pleased the crowd was fashion entrepreneur Donatella Versace, sister of slain gay designer Gianni Versace. She was part of a string of celebrities and other notables appearing on floats in addition to the “Pose” cast, from Vanessa Williams with radio station KTU, Felipe Rose, better known as the Indian from the Village People, with God’s Love We Deliver, and Judy Shepard, the mother of murdered gay college student Matthew Shepard. Barnes and Noble sought to honor famous LGBTQ writers and activists for other causes in its contingent, with writers like Sam Miller, Mona Eltahawy, and others carrying placards of their own or others’ works.

Following an apology from New York City Police Commissioner James P. O’Neill for his department’s role in the original Stonewall raid that led to the riots, WorldPride 2019 seemed to be one where the police perhaps exuded an especially tangible friendliness. Officers at times danced with parade-goers and adorned themselves in rainbows stickers and other paraphernalia, their uniforms coming to match the rainbow-swathed NYPD police cars launched for this year’s Pride season.

Gay Pride is arguably the most visually striking of all of New York’s parades. Caribbean contingents brought a feathered sense of Carnival to the parade, mesmerizing the crowd as usual. Formed with the help of many contingents was a massive rainbow flag, which stretched for blocks along Fifth Avenue, stepping off long after nightfall, the art-deco crown of the Empire State Building shining above it in a complementary pattern.

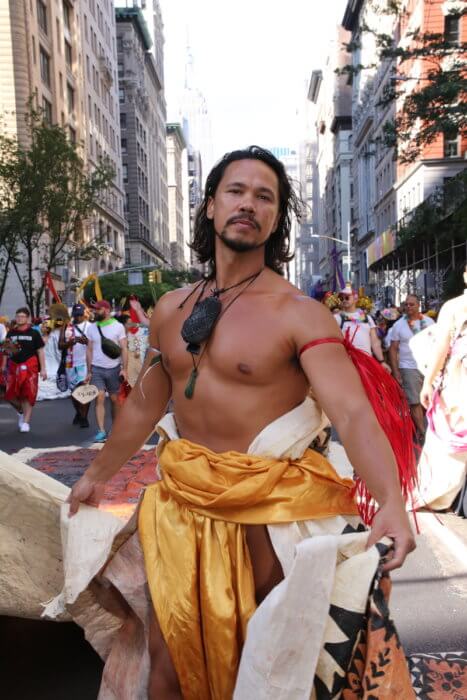

Still, some of the most visually impressive also broke the rainbow mold. These contingents included the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, in partnership with Deutsche Bank and the drum band Fogo Azul, its participants carrying Renaissance-style banners honoring LGBTQ artists, alive and departed, as well as UTOPIA, whose members adorned themselves with clothing made from traditional Polynesian tapa cloth, some capes trailing many yards behind them along the pavement. Out Olympic swimmer Amini Fonua of New Zealander and Tongan descent was among those in the contingent.

The most striking aspect of the parade was how long it actually lasted, along its route from 26th Street and Fifth Avenue, where it passed the Flatiron Building, bending along into Greenwich Village to pass the Stonewall Inn, before returning uptown, past the new AIDS Memorial on Seventh Avenue. Though scheduled to end around 11:00 p.m. according to the organizers, floats and contingents were still stepping off around that time. Among the very last of the international groups was Taiwan, where same sex marriage just became the law of the land, hours off schedule. Still, diehard fans were along the route cheering the parade into the next morning.

This was, for sure, a Pride like no other.