Sometimes it feels like the late German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s image as a bad boy has outlived his films. While Robert Katz’s tabloid bio “Love Is Colder Than Death” (named after Fassbinder’s first film) remains out of print, documentaries like Rosa von Praunheim’s “Fassbinder’s Women” and numerous supplements on Criterion releases of Fassbinder’s work have kept the director’s cult of personality alive.

To be sure, he was one of the first prominent filmmakers who was openly gay, and his life was scandal-sheet fodder: non-stop work and a personal life marked by troubled relationships followed by an early death, apparently from a drug overdose, at age 37 in 1982. A new documentary, “Fassbinder: To Love Without Demands,” takes a Freudian approach in trying to get beyond titillating subjects in Fassbinder’s life like “Sadomasochism” and “Death,” which are two of the film’s actual chapter headings.

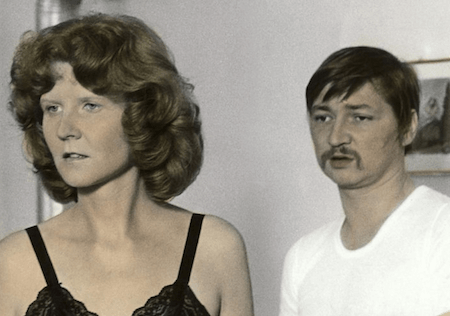

Director Christian Braad Thomsen, who was born in Denmark but delivers a voice-over in German, knew Fassbinder personally and interviewed him several times. His film is largely based around two interviews with Fassbinder, one conducted in 1972 and the other in 1978. In the latter interview, Fassbinder appears to be totally exhausted. He holds a glass of amber liquid in one hand and a cigarette in another. Yet he’s extremely articulate, even if he speaks slowly. Thomsen also interviews two members of Fassbinder’s acting troupe, Harry Baer and Irm Hermann, and incorporates audio-only clips from Fassbinder’s mother and frequent performer Lilo Pempeit and actress Margit Carstensen.

Interviews from 1970s at the heart of a psychological profile

Hermann seems to be in a healthier state of mind than she was when living with Fassbinder and acting in his films. In fact, she sounds downright jovial when stating, “Fassbinder treated me like a prostitute,” and relating anecdotes about how the director destroyed a bookcase when he realized she was hiding her savings from him there. Baer was treated somewhat better by Fassbinder, but he has plenty to say on the subject of “sadomasochism.” He complains that Fassbinder took advantage of his looks by forcing him to play nude scenes constantly.

Thomsen finds the problems that marred Fassbinder’s life and fueled his creativity in his childhood. Raised in an extended family, he suggests that Fassbinder lived out the Oedipal scenario: around age five, he succeeded in “killing off” his father, who abandoned the family then. From a certain perspective, this can be seen as giving the young Fassbinder a great deal of freedom; from another, it led to an unhealthy neglect.

Very late in “Fassbinder: To Love Without Demands,” Fassbinder is interviewed on the set of his final film, his adaptation of Jean Genet’s “Querelle.” Asked for his thoughts on the treatment of homosexuality in cinema, he replies that it’s always been depicted very badly, but that “Querelle” isn’t about gayness, just an individual searching for his destiny.

Gay activists and feminists weren’t pleased by “Fox and His Friends” and “The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant,” films that suggest that LGBT people are no more liberated than heterosexuals. In Thomsen’s 1972 interview, Fassbinder suggests that feminists’ goals of emancipation are easier talked about than achieved in a male-dominated society. At the same time, he opines that women make more interesting film characters because they’re allowed to express their emotions openly.

“Fassbinder: To Love Without Demands” is damaged by its reliance on audio-only interviews, which are generally played over zooms into still photos. Of all directors, Thomsen seems influenced by Ken Burns. To be fair, he makes judicious use of clips from Fassbinder’s films, but “Fassbinder: To Love Without Demands” would be far less fascinating without the 1978 Fassbinder interview. There, Fassbinder fully expresses the contradictions of his life and work. He yearns after an equal, utopian relationship while suggesting that in a late capitalist society, it’s probably impossible.

If his films have influenced directors like Lars von Trier and Todd Haynes, his personal life was less worthy of emulation, to put it mildly. This interview makes it clear that he knew his failings and was perfectly capable of analyzing them. If he’d been able to escape or transcend them, he might have lived past 1982 and had a film at the 2015 Berlin Film Festival, where “Fassbinder: To Love Without Demands” premiered.

FASSBINDER: TO LOVE WITHOUT DEMANDS | Directed by Christian Braad Thomsen | Self-distributed | In German with English subtitles | Opens Apr. 29 | The Metrograph, 7 Ludlow St., btwn. Canal & Hester Sts.| metrograph.com