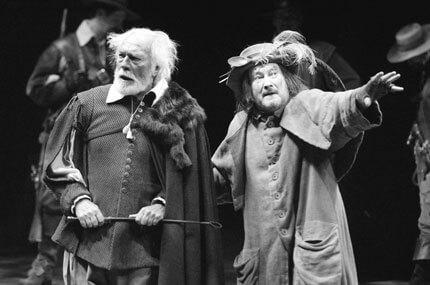

Christopher Plummer manages an astonishing Shakesperean feat

Were it not for Christopher Plummer’s astonishing performance in the title role, the new production of “King Lear” would fall into the category of “good for you” Shakespeare—the kind of straightforward reading and conservative, if well-executed, mounting one expects from repertory theaters.

That said, Plummer’s performance at Lincoln Center elevates this production and makes it relevant for a contemporary audience. He takes a role that is, oddly enough, a small part, and supplies enough passion and technique for an entire cast.

This story of an ego-driven man fighting against forces outside his control, including the encroaching grasp of the tomb, is a well-known tale. Turning away from love and support, Lear struggles to impose his will on the world—on questions ranging from how he will be treated by his daughters to how he will hold on to the throne—only to lose all in the end. Plummer’s scathingly poignant portrayal of Lear’s descent into madness is not histrionic, but insightful in depicting the inevitable reaction of a mentally ill man lashing out at the collapse of the support structures in his life.

Plummer’s performance will be chillingly cathartic for anyone who has witnessed a person slipping into delusion. In his striking performance, Plummer roundly answers why finely rendered contemporary Shakespeare is still relevant.

Minus Plummer’s performance, this “King Lear” risks becoming staid. Director Jonathan Miller’s preoccupation with constructing stage pictures is an approach that is as dated as it is stiff. This is a highly visceral play, a classic Elizabethan revenge tragedy in which nature is the great deliverer of that revenge. The production seems held back, the actors posed, and the illicit passions and unstinting evil of the secondary characters that is so present in the text is never felt from the stage here. One of the great pleasures of “King Lear” is reveling in just how rotten some of these people are, but Miller has tamped it down, shortchanging the play and the audience.

“King Lear” is lusty, bawdy and filled with all kinds of violent emotions, but Miller has chosen instead to deliver a production that feels sanitized and bland.

This “King Lear” is especially disappointing given the consistently thrilling production of “Henry IV” recently staged in the same theater. Those performers who do manage to break out of the constricting production acquit themselves well. Domini Blythe as Goneril has some of that all-consuming evil that makes the character such a delight. She seems to have been directed not to move her lower body, though, so she has to do everything with her voice and fierce eyes—and she does it well.

Ian Deakin in the small role of the Duke of Albany and Goneril’s husband, is the benevolent flip side of his wife and quite engaging. Geraint Wyn Davies plays Edmund, Lear’s bastard son and the catalyst for the destruction that ensues as he tries to claim the throne by vilifying his legitimate brother Edgar. While Davies’ is a one-note performance, it enlivens the proceedings.

On the other hand, there are missed opportunities in other performances. Miller doesn’t seem to know what to do with the less black-and-white roles of the Earl of Gloucester and Kent, who stay loyal to Lear. As a result, the performances by James Blendick and Benedict Campbell, respectively, lack cohesion, with Gloucester accepting the gouging out of his eyes with unusual equanimity. Blendick becomes a kind of blind Mr. Cellophane, a character like the Amos of “Chicago” who says people “look right through me.” This performance undermines the production’s overall potential,

In the role of Edgar, Brent Carver is simply an embarrassment. He gives a shallow undeveloped performance, and much worse, he remains virtually unintelligible throughout the evening. His character is pivotal, yet after several scenes of straining to comprehend two consecutive syllables, one just gives up.

Claire Jullien is a very wooden Cordelia, distant and removed, which makes it very difficult to care for the character—a critical element if one is to fully feel the tragedy of Lear.

For all the highbrow interpretations of Shakespeare, these plays are not merely exercises in high art for the intelligentsia. They can be astonishing pieces of theater and must not be robbed of their vitality by making them pretty entertainments for those who don’t want to feel. It’s a shame Miller doesn’t seem to get this. However, it’s a blessing that Plummer refuses to play that game.