James McArdle and Andrew Garfield in “Millennium Approaches,” part 1 of Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America,” directed by Marianne Elliott, at the Neil Simon through July 1. | BRINKHOFF & MÖGENBURG

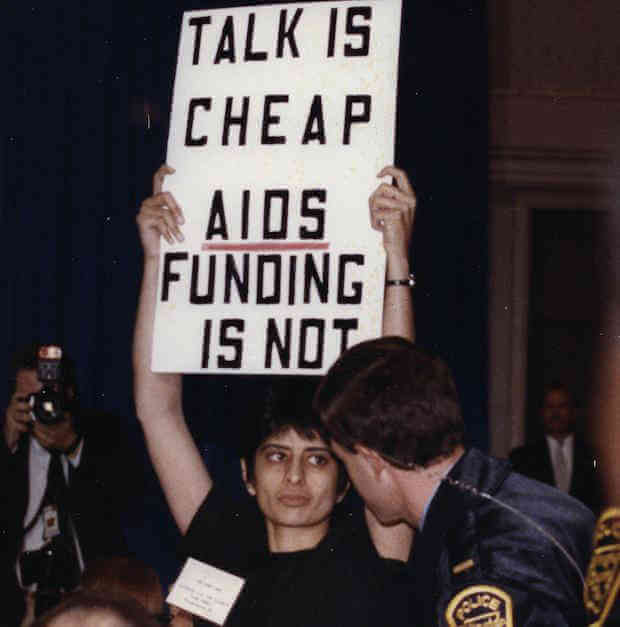

If you have seen “Angels in America” in any of its previous incarnations — the original 1993 Broadway production, the fine 2003 HBO film, many regional productions, or the 2010 Signature revival, you may understandably wonder whether you should see it again, invest another eight hours of your life in Tony Kushner’s complex, sprawling, and abstract meditation on life and love, AIDS, angels, activism, faith, passion, and the entire world. The simple and inescapable answer is: you must.

The sheer brilliance of Marianne Elliott’s production, imported from London’s National Theatre, and the extraordinary virtuoso performances by the stellar cast will leave you emotionally and intellectually exhilarated — and drained —particularly if you see both parts in one day, which is highly recommended for the full impact of the experience. It is both hilariously funny and achingly sad, and what’s remarkable is that 25 years after the original productions of the two parts, “Millennium Approaches” and “Perestroika,” the plays are still relevant and gripping. For those of us who remember the 1980s, saw how AIDS tore up gay culture, and went to too many funerals of friends we loved, Kushner’s rage was cathartic — and comforting. In his poetry and abstraction, there was a kind of shared, very public mourning for the cruelty of a largely inexplicable disease and the realization that those in power didn’t care that an entire swath of the population was dying while being actively ignored. Even so, life would find a way and the struggle would continue.

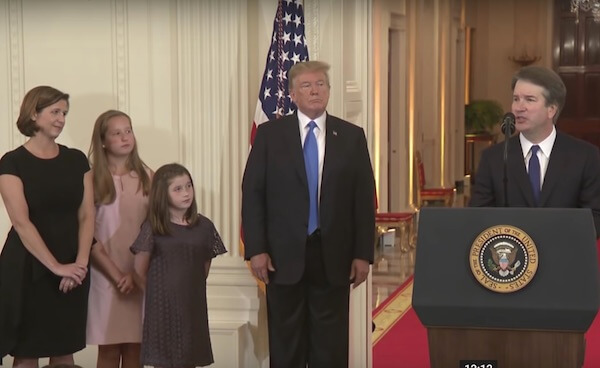

A quarter of a century later and 18 years in to the new millennium, it’s clear it did not bring the promised enlightenment and that the struggles are still real, if somewhat changed. PrEP has significantly slowed the transmission of HIV, nor is the virus an automatic death sentence. Yet there are still nearly 40 million people worldwide living with HIV. The infamous lawyer Roy Cohn, who figures prominently in the plays, has moved out of the shadows of history thanks to his mentoring of one Donald Trump during the president’s early career. The nation throbs with rage and ignorance, fueled by a hostile administration, religious posturing, and a media thriving on — and so all too eager to stoke — the fires of divisiveness. Seen against this backdrop, “Angels in America” takes on mythic and metaphoric proportions that give the piece a wrenching immediacy that seizes the audience’s mind and heart and refuses to let go.

The monumental revival of “Angels in America” is an unqualified triumph

The complex and intertwining plot lines have characters meeting and interacting in reality and in each other’s hallucinations. Its scale resists easily description. The natural and supernatural co-exist as Prior Walter, a young man and former drag queen stricken with AIDS, is visited by ghosts of his ancestors, also named Prior Walter, who herald the arrival of an angel, who calls him a prophet. Meanwhile Joe Pitt, a transplanted Mormon in New York who is struggling with his homosexuality, falls under the mentorship and manipulation of Cohn. Joe’s wife Harper is a valium-addicted woman at sea and despairing. Cohn is diagnosed with AIDS and is visited by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, whom he sent to the electric chair in 1953. Prior’s lover Louis can’t take the pressure of the illness and abandons him. Fortunately, Prior’s friend Belize, another former drag queen and now a nurse, is there to help. He also happens to be Cohn’s nurse. The angel arrives and tells Prior that Heaven — supposedly a beautiful city, like San Francisco — is in upheaval, left that way by God’s preference for human life. Prior is charged with spreading the world for humans to “stop moving” in order to restore order in Heaven, and as the angel says, “The great work begins.”

Nathan Lane and Nathan Stewart-Jarrett in “Perestroika,” part 2 of “Angels in America.” | BRINKHOFF & MÖGENBURG

In part two, Joe’s mother arrives to save him from his sexuality, Harper goes off the rails, Cohn is disbarred and dies as Rosenberg watches, and Belize steals Cohn’s questionably obtained AZT for Prior and others. Joe and Louis find each other and enter into a sexual relationship that ends badly. Harper leaves for San Francisco. Four years later, Prior is still alive, to his surprise. As he says at the very end of “Perestroika,” “The world only spins forward. We will be citizens. The time has come. Bye now. You are fabulous creatures, each and every one. And I bless you. More life. The great work begins.”

This message of cautious hope, as simple as it is on the surface, lands with surprising impact. It is ultimately the only possible prophecy, and one we need today as much as we did a quarter of a century ago.

Elliott’s production mines all the artistry of the text with sublime attention to detail. Kushner’s original stage directions stated the play should be presented simply, with no blackouts between scenes, so its theatricality would reflect its structure. Ian MacNeil’s set is largely a series of forms framed with neon on turntables that assemble into rooms and different locations. Paule Constable’s lighting uses darkness with great sensitivity, using specific points of illumination to striking theatrical and emotional effect.

And then, there’s the cast. There are barely words to describe Andrew Garfield’s brilliant performance as Prior. He tackles the role with a no-holds-barred ferocity and focus that are often literally breathtaking. His technique as an actor combined with the integrity of the portrayal and his inherent presence are something you won’t see often in a lifetime of theatergoing. It is a performance that will resonate for years to come. Nathan Lane is equally galvanizing as the nefarious Cohn. His performance has the hardness, dazzle, and clarity of a perfect diamond.

James McArdle as Louis brings life and sympathy to an often-unlikable character. Here, his struggle is highly relatable and his unresolved journey beautifully reflects the reality of the world around him. Louis and Joe, performed with extraordinary depth and range by Lee Pace, are the two characters most grounded in reality, who have neither visions nor visitations but must slog through their daily existence desperately seeking answers.

Denise Gough as Harper gives an intense performance as Joe’s wife. Harper is increasingly unhinged as the myths she’s built her life around — Mormonism and marriage — are ripped away from her. Like the others, she has no choice but to continue moving and finds hope in her realization that “in this world, there is a kind of painful progress” — what Shakespeare called “a glooming peace.” Coming at the end of a tempestuous ride, Gough in her quiet last scene has an understated power that makes the performance.

Nathan Stewart-Jarrett as Belize is also a more reality-based character, delivering humor and perspective that is often moving. Belize is a foil to Louis and Cohn, and Stewart-Jarrett makes him compelling and loving, a rare island of warmth in the cold world of the plays. Amanda Lawrence and Susan Brown take on multiple smaller roles, including the Angel and Joe’s mother, respectively, and like the rest of the company shine in all of them.

With this revival, “Angels in America” becomes the “great work” itself. It is at once historic and vital, an intimate love story and an epic. Kushner has called this a comedy, but in the sense that Dante meant it. It is life in all its confusing despair and beauty. If that’s what you go to the theater for, do not miss this production.

ANGELS IN AMERICA: A GAY FANTASIA ON NATIONAL THEMES | Neil Simon Theatre, 250 W. 52nd St. | Through Jul. 1: Both parts: Thu. & Fri. at 7 p.m. or Sat. at 1 & 7 p.m.; Part 1, “Millennium Approaches,” only: Wed. at 1 p.m.; alternating Sun. at 2 p.m.; Part 2, “Perestroika,” only: Wed. at 7 p.m.; alternating Sun. at 2 p.m. | $49.50-$249 for each part at angelsbroadway.com or 800-745-3000 | Part 1: Three hrs., 30 mins., with two intermissions; Part 2: Four hrs., with two intermissions