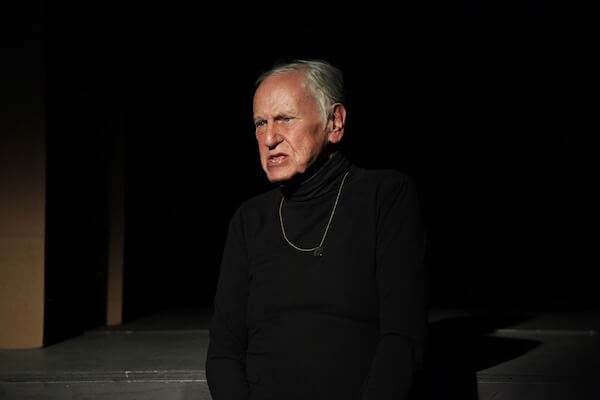

Playwright Robert Patrick. | THEO COTE

BY DAVID NOH | I was there, in the madding crowd, and can attest that thousands of impressively fired up queer activists showed up for the Christopher Street rally on February 4. But there was another equally impressive gay gathering of fervent minds and hearts taking place at La MaMa, which I also attended. That was the 140th edition of its regular series, Coffeehouse Chronicles, reuniting in a sterling panel theater folks who were in at the very beginning of the downtown Off-Off-Broadway theater movement of the 1960s. The panel centered around the career of playwright Robert Patrick, 79, and featured William Hoffman, Michael McGrinder, Natalie H. Rogers, Jordan Beswick, Carol Nelson, Magie Dominic, and Jason Jenn. This panel was presented as part of the revival of a quintet of Patrick’s short plays, produced in a show titled “Hi-Fi, Wi-Fi, Sci-Fi.”

In an interview at La MaMa, the boundlessly effervescent playwright told me, “I don’t know anything about the production of these old one-acts of mine, I’ve not been allowed to see the show. It’s so technically complex they can’t casually do a run-through of it, so I’m not going to see it until tomorrow night, which is the first preview. They decided that these plays from the 1960s predicted the Internet, social media, and various technical things.”

Often called one of the architects, or at least godfathers, of both Off-Off-Broadway and gay plays, Patrick modestly decried such titles: “I always like to tell people we didn’t set out to start gay theater. Joe Cino gave us the freedom, saying, ‘Do what you have to do.’ And it happened that, back to back, Lanford Wilson and I decided we had to write about the gay life around us in New York, with no political intentions or claim to be brave pioneers whatsoever.

Robert Patrick’s triumphant return to his Off-Off roots

“It was very casual: Joe gave us the floor, we did our shows, and, to our surprise, that led to more people saying, ‘You do gay shows here? I always wanted to write a gay show but didn’t know you could put it on.’ One night, during my first play, which was the second gay one after Wilson’s beautiful ‘The Madness of Lady Bright,’ William Hoffman [‘As Is’] and I were acting and he had a monologue, during which I went across the stage and leaned against a café table. There was a boy there with his parents in the audience, and I overheard him saying, ‘Mom, Dad, you see that man there? Well, I brought you here because I wanted you to see him. I’m like him. I’m a homosexual.’

“And that was the first moment I realized that we might be doing something a little larger than producing a weekend’s entertainment, there might be repercussions. This was 1964, and Joe let a half-dozen others do gay plays before the Caffe closed. The producers of ‘Boys in the Band’ were big fans of Cino, and I think seeing our plays made them think it was possible for them to produce that wonderful play, which was the first to reach the commercial world, although a lot of people think it was the first gay play.”

Recalling his role as the Cino doorman, Patrick said, “I was lucky to squeeze 50 or 60 people in. A couple of our hits like ‘Dames at Sea’ or ‘A Funny Walk,’ by that genius Jeff Weiss, would have people in the ceiling loft. People agree that Jeff was one of two or three outstanding talents of Off-Off-Broadway, whose lover recently died. Although it’s a terrible thing to say, maybe this will free him up to write more plays. Jeff’s plays became ever more violent and angry. The sweat from his arms would shower the audience, and I’d say, ‘Jeff, what are you doing?’ He’d answer, ‘Bob, acting is very bad for me and I shouldn’t do it, but as long as people pay attention, I will. But I’m trying to get so frightening, they won’t come anymore and I can lead a normal life.’”

A child of the Depression, Patrick’s parents were migrant workers: “The first time I ever went to school for one year was my senior year. I was jerked around and never socialized and never learned to make friends. I sought friendship and community in the movies and radio. Then World War II saved the Southwest and my Daddy got a job in the Navy and Mama manufactured airplanes and we got a house. Mama was so tiny she could climb into the wings of a plane and weld, so she was in demand.

“I had two and a half years of college but was the world’s worst student, barely scraping by, grade-wise, but I took advantage of the library. It was my first-time access to a really good library, and I learned about the wonderful world of past theater. I then went through all these crazy adjustments — the Air Force, jobs in various cities, had myself put in the loony bin. I’d decided there was something wrong with me, and they had to take you in if you went there. They took me in for two weeks, exactly, and kicked me out, saying, ‘Just move to a bigger town.’

“Fate brought me to New York City on September 14, 1961. I was passing through to see Greenwich Village, and I followed a pretty boy into the Caffe Cino, which turned out to be the hub of modern and gay theater, and I stayed. I struck up an affair with a Cino waiter, who went away in 1961, and just yesterday I’m sitting on the stoop here, smoking a cigarette, and he walked by. He wouldn’t believe I was looking for him for 60 years!”

Patrick decided to stay at the Cino, “the first place where I ever found a community of people not afraid to be artistic, intellectual, gay, or sexual. I took a job at Macmillan Publishing on Fifth and 12th Street, so I could always run to the nearby Cino. For three years, I worked there for free, like many did, sweeping, shopping, mopping, waiting tables, whatever they needed. One day, I was helping, moving in the scenery for Lanford’s first play, and the stage manager and director were putting the sofa onstage, opening and closing it.

“Watching them in silhouette, I suddenly knew who they were and why there were doing it, and suddenly had an idea for a play, although I had never thought of writing plays. I’d been around a new play a week for three years and went home and wrote it. But Joe didn’t want to do it because he said, ‘Playwrights are terrible people, and you are too nice.’ But the other playwrights insisted he do it, because I was a good guy and pulled my own weight. So we did ‘The Haunted Host’ in 1964, which Harvey Fierstein has done four times.

“One day, Lanford came running down the street and said, ‘Bob, you gotta see this woman! She’s a black Marlene Dietrich [at what was then the original La MaMa basement space on Ninth Street]. It was Ellen Stewart, who originally was not so much about plays, as her own personality. God knows, that started out immense, and as she learned to express herself, it became cosmic. La MaMa would step out onstage down here. and you were in a new world. It really never mattered what was onstage — she was just this immensely resourceful and dedicated person.

“She was never going to produce theater but she had a man who wanted to do plays so she rented space for him. Someone from the Cino brought one of their shows to her, and then another, and suddenly she was a producer. The police would see all these white boys going into this basement where this black women lived and thought she was a prostitute. Extraordinary woman, and I’m surprised there isn’t a big movie based on her life.”

Patrick came to mainstream recognition — and the strange uptown world of Broadway — with his play “Kennedy’s Children”: “I was at La MaMa, doing a play a week, sometimes two or three a week. I had a stack of new plays beside me, and this boy came in and said, ‘I’ve been offered a chance to direct!’ I said, ‘Take what you like,’ and it happened that the top script on the pile was ‘Kennedy’s Children.’ That production worked fine, and in it was an actor who played the silent role of the bartender. He said, ‘I’d like to option this play,’ which to me was then a funny idea, like something uptown, optioning plays. He gave me a contract and a check and went off to try and find a producer because he wanted to be in it.

“Every now and then I’d get a letter saying, ‘The University of Minnesota turned it down so I’m going to San Francisco. Here’s a check.’ No one in Paris or Mexico wanted to do it but the checks kept coming. Finally I was opening La MaMa Hollywood for Ellen, and got a call from these people in London who were doing it in the backroom of a pub, the King’s Head, and wanted to bring me over. The pub owners were sure that no one would like it, but they were bankrupt and closing, so they might as well close with a play they liked. The morning after it opened, I signed a contract for it to be translated into 60 languages!

“It was done all over the world, and there was a man here who wanted to option it for Off-Broadway. I was so arrogant and indifferent and didn’t even want to come back to America, so I said, ‘It’s Broadway or nothing,’ and he said, ‘All right.’ It was absurd and not appropriate for Broadway in 1975; if we had done it Off-Broadway, which this sensible man wanted to, it would still be running.”

In the Boston tryout, the Wilbur Theatre begged to let it keep the play for four months, knocking everything else off its schedule, it had been so rapturously received.

“Absolutely brilliant production but we had booked the Golden Theatre and had one afternoon in it before opening night. It was then that I realized why we got the theater so cheaply. ‘Grease’ was next door and our poor actors had to completely alter Clive Donner’s wonderful staging and just come down front and shout the lines. They did that very well, but it was not the show it was in Boston, and it eked out a puny two months-run, which made me famous, although I was stupid not to do it Off-Broadway.”

Backtracking to trace the play’s origins in the London production, Patrick explained, “Clive got Glenda Jackson to be in it, in this pub, but then she called him, ‘Darling, some fool has offered me a million dollars to appear in a film and I thought it would be rude to refuse him!’ Then we looked in a wonderful book featuring every actor available in London and there was Shirley Knight. She’d left Hollywood, so she read it, and said, ‘This is not a play, just a series of monologues. No thank you.’ Then Jackson got her friend Vivian Pickles to do it, who was marvelous.

“We got to America and cast everyone except for the sex symbol goddess girl. We saw girl after girl — no one was right. The phone rang and it was Shirley Knight’s agent: ‘Miss Knight is in New York, heard you were casting, and wonders if you are still interested in her.’ My God, yes, and it was literally at the first reading the next day that Shirley came in and started reading the teacher’s role. She and the woman cast in that part looked at each other and then me. ‘No.no, dear,’ Clive said, ‘it’s the other role.’ ‘You want me to play a hippie?’ ‘No, Shirley, the other role.’ ‘You mean Carla? I read the script and it seems to me that Carla is an intelligent, strong, and articulate woman who has simply come up against a force larger than she is. She really is a heroic figure. You want me to play an intelligent woman?’ Clive said, ‘Please!’ And she said, ‘All right!’ and won her Tony. But to this day she swears she doesn’t remember that.”

A vibrant Broadway career should have happened after that, yes? No.

“They hated me in America,” Patrick said. “The London critics had somehow made a point of dishing the American critics for not having discovered me, so you can imagine their response. This sounds like a paranoid playwright story, but I did a New York Times interview and a photographer friend took a whole box of photographs of me to run with the story. The boy who interviewed called me backstage at the Golden: ‘I got to tell you. You’ve got to be prepared, you’re such a nice guy. I was told to make you look like an idiot and you won’t believe the picture they chose of you. They’re so angry because the London papers dished them. I can’t change this, and if you tell people, I will deny it.’ They’d chosen a joke one of me, leering, and the entire interview consisted of snatches of other quotes and me talking a lot of nonsense.

“I was not good at success. I didn’t like the world it puts you into, and I wasn’t adroit at it. Those two factors blew many opportunities that came to me. I was vulgar, lewd, drunken, arrogant, insensitive, and careless of other opportunities for both myself and other people. I’m not suited for success — even this interview is embarrassing to me, although you see I’ve overcome it [laughs]. It’s not what I do shows for — nothing wrong with being an attention hound, I just don’t happen to be one.

“I met an awful lot of the most successful people in movies and stage during this whirlwind thing, and they were all, to a person, miserable, what I call negative narcissists, thinking only of their own failure. I was on an elevator in Beverly Hills with Elton John and Paul McCartney and they were arguing over which of them was the biggest failure, whose career was most finished and comeback would never happen, but each claiming it as a kind of virtue. Everyone wants to be there, fights to get there, and I guess every move down a notch feels like the beginning of the end.

“I may have had an attitude that attracted bad luck — chasing prominent actors who wanted to act in my plays but always losing them to more lucrative TV/ movie offers. I liked the money, but there was no life. I left New York for Los Angeles when the actress Carol Nelson, with whom I’d done a dozen plays, asked me, ‘Bob, why do you do this?’ I could not come up with an answer.”

Patrick, who has never really had a life partner (“a few affairs’), lives quite contentedly now in the Los Feliz area of LA. He’s given up playwriting, and, for a time, he made a very good living reviewing gay porn DVDs, a gig that dried up when everything went to the Internet. He’s been discovered by younger California bohemians who produce, as well as flock to his solo cabaret shows, where he sings his own original ditties. It’s a new, very agreeable career for him, and he’s always believed that all plays should be musicals, anyway.

“Lanford Wilson, Tennessee, their plays are musicals: all you have to do is take a breath and say the words. Plays should have a verbal style that will carry the actors through emotional changes and encounters and nuances, and I feel that I did that more successfully in my personal favorite play, ‘Michelangelo’s Models’, and also ‘Judas,’ which once had the interest of every major English-speaking actor from Gielgud to James Mason for the role of Pontius Pilate.”