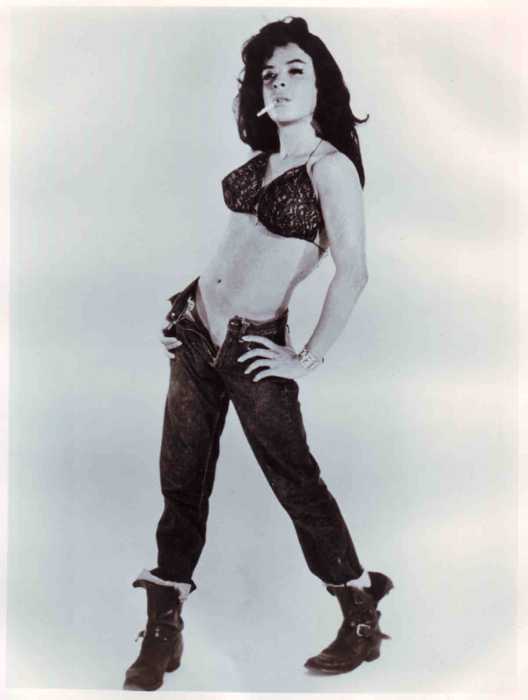

Lawrence Ferlinghetti in front of his San Francisco bookstore and publishing house, City Lights. | FIRST RUN FEATURES

Christopher Felver’s affectionate 2009 documentary “Ferlinghetti: A Rebirth of Wonder” may be reaching cinemas years late — and after both “Howl,” the 2010 film about Allen Ginsberg, and the recent adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road” — but this profile of arguably the most important Beat poet, painter, and publisher is worth the wait.

Yonkers-born Lawrence Ferlinghetti is justly famous for his bestselling poetry collection “A Coney Island of the Mind.” Snippets of several remarkable poems from that volume, including “I am Waiting,” “Autobiography,” and “Dog” — that last being read with a terrific black and white video of the title animal cavorting about on screen — are employed to demonstrate not just the author’s wonderful, accessible prose, but also his fierce political-mindedness.

The film explains that one of his untitled poems from that collection — about the crucifixion of Jesus — angered the American Legion and the Catholic Church. It was not Ferlinghetti’s first time in trouble for creating material deemed offensive. In 1957, as publisher of Ginsberg’s “Howl” and owner of City Lights Books, where it was sold, he faced obscenity charges and possible prison time. He ultimately won a landmark decision for First Amendment rights. Footage of Ferlinghetti recently being honored for his work on the steps of City Lights underscores the undiminished importance of that half-century-old civil liberties victory.

Christopher Felver’s telling of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s life captures spirit, rhythm of the Beats

The documentary does not indicate the dates of many of the videos, interviews, and photographs presented, which is a drawback for viewers trying to understand the specific narrative chronology, but this oversight does not detract from the film’s major themes. The most important through-line in Ferlinghetti’s life and career was his commitment to speaking out against injustice. Footage of the poet with the Sandinistas in Nicaragua and testimony from friends and fellow artists such as Dennis Hopper, Michael McClure, Amiri Baraka, and Anne Waldman, in different ways, underscore this point.

In one telling sequence, Erik Bauersfeld, a radio dramatist, describes Ferlinghetti’s insistence that he is a lyric poet, not a political poet, because “politics are passing.” The writer tries to find “timeless subjects with crucial political ideas,” we learn. Ferlinghetti is seen posting savvy political messages — about making oil a public utility or about gun control — in the windows of his City Lights shop. He calls these screeds his “blog.”

Ferlinghetti’s wit is another recurring theme in the film; we see him addressing the special bond between San Francisco poets and visual artists in Los Angeles and riffing about the “role of the artist” while driving around San Francisco. He is full of charm and clever wordplay when talking about hot cross buns and croissants, joking around on Ellis Island, and smiling on Via Ferlinghetti, the San Francisco street named for him.

There are some curious gaps in the film’s account of Ferlinghetti’s life. We learn about his decades-long friendship with George Whitman, the owner of the Shakespeare & Company bookstore in Paris — the two attended the Sorbonne together and once talked about swapping stores for a year. But, major elements of Ferlinghetti’s personal life — his marriage and kids — are barely acknowledged. It is something of a shock when his son, Lorenzo, appears on screen to celebrate his 45th birthday.

There is a fascinating and nicely detailed segment early in “Ferlinghetti” in which Giada Diano, the writer’s biographer, recounts the unusual story of his childhood. A judiciously edited assemblage of photographs shows an orphaned Ferlinghetti growing up among the Bislands, a wealthy Bronxville family who adopted him when his aunt left him in their care. Serving in the Navy during World War II, he witnessed the D-Day carnage from the safety of a ship, and his visit to Nagasaki after the bombing turned him into a pacifist, a significant turn in his political awakening.

The film’s evocation of Ferlinghetti’s bohemian spirit is what makes it an invaluable portrait. A TV clip shows Ginsberg and him discussing overpopulation. Ginsberg waxes prophetic about threats to adequate water supplies and to the ozone, and we later see Ferlinghetti in a park reading a poem entitled “The Breeding Blues.”

In another scene, Ferlinghetti is eloquent while reading a poem about Ginsberg, who is dying. The pain in his voice about losing his confidante and co-conspirator is affecting, especially as beautiful black-and-white images of Ginsberg fill the screen.

“Ferlinghetti” may hopscotch through its subject’s life to create its portrait, but Felver’s approach — jazzy and spontaneous, not unlike the poetry and music of the Beats — is appropriate. The resulting mosaic portrait emphasizes that Ferlinghetti unfailingly used his life, his poetry, and the works of other poets he published as opportunities to be a dissenter, a subversive, and an agent for change.

FERLINGHETTI: A REBIRTH OF WONDER | Directed by Christopher Felver | First Run Features | Opens Feb. 8 | Quad Cinema | 34 W. 13th St. | quadcinema.com