Hilary Harkness’ grim, expressionless women join the current media buzz

The timing of Hilary Harkness’ debut at Mary Boone Gallery couldn’t be better. The popular media is awash with images of casual female sadism, from the recently released teen flick “Mean Girls,” to the pictures of Private Lyndie England smirking and mugging for the camera with her Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

It’s a range of sins, from venial to mortal, each attesting to an appetite for the shock and awe provoked by watching women behave badly. Among them we find Hilary Harkness, seemingly fascinated by humiliation and punishment.

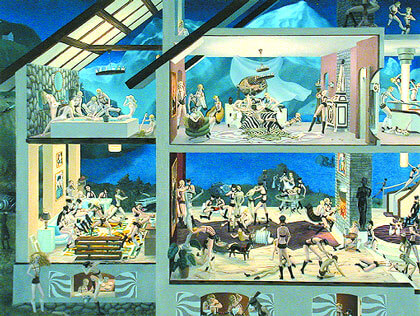

Harkness paints dense, cross-sectional interiors that swarm with armies of identical female protagonists engaged in variety of rough scenarios. We find three of her small canvases in the enormous soaring space of the Boone Gallery, which require the viewer to get very close to observe veritable microcosms of S/M activity. The use of forced perspective and compartmentalized space further heightens the pleasure of looking long and closely, as one would at dollhouses or architectural diagrams.

Surfaces smoothed by a steady brush, reminiscent of American regionalists such as Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, depict closed societies of women in uniform––WACs, nurses, leather girls, and what can only be called “Heidis” due to their perky blond pigtails.

While a Bond Girl or one of Russ Meyer’s Super Vixens might cheekily display her ample bosom as a source of “grrrl” power over both viewer and opponent, Harkness’ swarms of languid, expressionless replicants have all the threat of a band of Gumbys. If the figures lack specificity and interest, Harkness stands at attention when she tackles the structural elements and fixtures of her interiors. Miniature guns, pipes, boilers, all manner of naval equipment, and hardware are beautifully and lovingly rendered.

Harkness’ body of work intentionally recalls the flavor of mid-20th century eroticism and magic realism. While artists such as George Tooker and the lesser known Pierre Klossowski (the elder brother of Balthus) come to mind, Harkness owes a particular debt to Paul Cadmus, in such works as “The Fleet’s In” (1934), and G.B. Jones’ brilliant lesbian recasting of Tom of Finland’s band of brothers. Where these artists imbue their pictures with a great lustiness and delicious sense of camp, Harkness’ pictures are singularly grim. The most perverse punishments in her paintings are saved for a group of pregnant figures, shedding light on a special brand of woman-generated misogyny.

Orchestrated all-female S/M scenarios hold a special pride of place in the popular erotic imagination. It’s too bad that Harkness is unable to treat this rich subject as little more than a bookmark within a text of possibilities.