The arrest of four young African-Americans for “masquerading” in 1966 illustrates the occasional complexity of police interactions with the LGBTQ community at that time and shows the emerging political power of the African-American community in New York City.

“Circumstances indicated that the above mentioned defendants were arrested and charged with going abroad in female attire and facial make-up in order to disguise their true identity, walking in an effeminate manner and speaking in a falsetto voice in public,” Sergeant George Forette, the commanding officer of the detective squad in Harlem’s 26th precinct, wrote in a February 20, 1966 memo to the NYPD’s chief of detectives. “One other person named Avon Wilson was detained for identification and claimed to have had a sex-change operation by Dr. Harry Benjamin… This subject was released upon verification of doctor.”

On February 13, Kenneth Uhl, a white patrol officer from the 26th precinct, assisted plainclothes officers in arresting Rudy Hunter, 22, Zane St. John, 22, Roland Wise, 21, and Lewis J. Charles, 26, at a bar on 125th Street that was called Joe’s Bar & Grille, Joe’s Place, or Joe’s Bar in police records. Wilson was not arrested.

The four were charged under a statute that effectively barred cross-dressing. The statute was enacted in 1845 to address an insurrection among Hudson Valley farmers who were objecting to high rents they had to pay. The farmers were killing sheriffs who were serving summonses on them and had taken to disguising themselves as “Indians,” as one court case said, or by wearing women’s calico dresses to avoid being identified. In the 20th century, the law was used to target the LGBTQ community.

“The section in its present form is aimed at discouraging overt homosexuality in public places which is offensive to public morality,” a judge wrote in a separate 1968 case. “In addition to a deterrent to sexual aberration, it is also addressed to crime detection and prevention of criminal activity.”

Forette wrote that “Premises known as ‘Joe’s Place,’ is the subject of recent communications alleging disorderly conditions and narcotics,” and then listed five reports by number that presumably referred to those communications.

In several published reports found online, Wilson was described as an early client of a clinic serving transgender people at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Benjamin was an early innovator in healthcare for transgender people. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health, which sets the standards of care for transgender people’s healthcare, was once named for Benjamin.

Gay City News found the records of the arrests and a few newspaper clippings discussing them in the files on the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) created by the NYPD’s political surveillance unit. That unit, which had various names since it began its work in the early 20th century, spied on CORE for more than a decade beginning in the early ‘60s. Founded in Chicago in 1942, CORE was a leading civil rights organization. CORE was active in supporting organizing in Southern states and opposing school segregation and job and housing discrimination in New York City.

An unsigned and undated handwritten note in the file says, “4 male negroes arrested for [Illegible] 887-7 CCP (masquerading wearing female attire and make up).” A news article that had its headline and date torn off says that police were in the bar “where, according to police, they were looking for female impersonators.”

What roused CORE in the Joe’s Bar incident was not the treatment of the four young African-Americans and Wilson, but how a sixth African-American who was in the bar when the arrests occurred was treated.

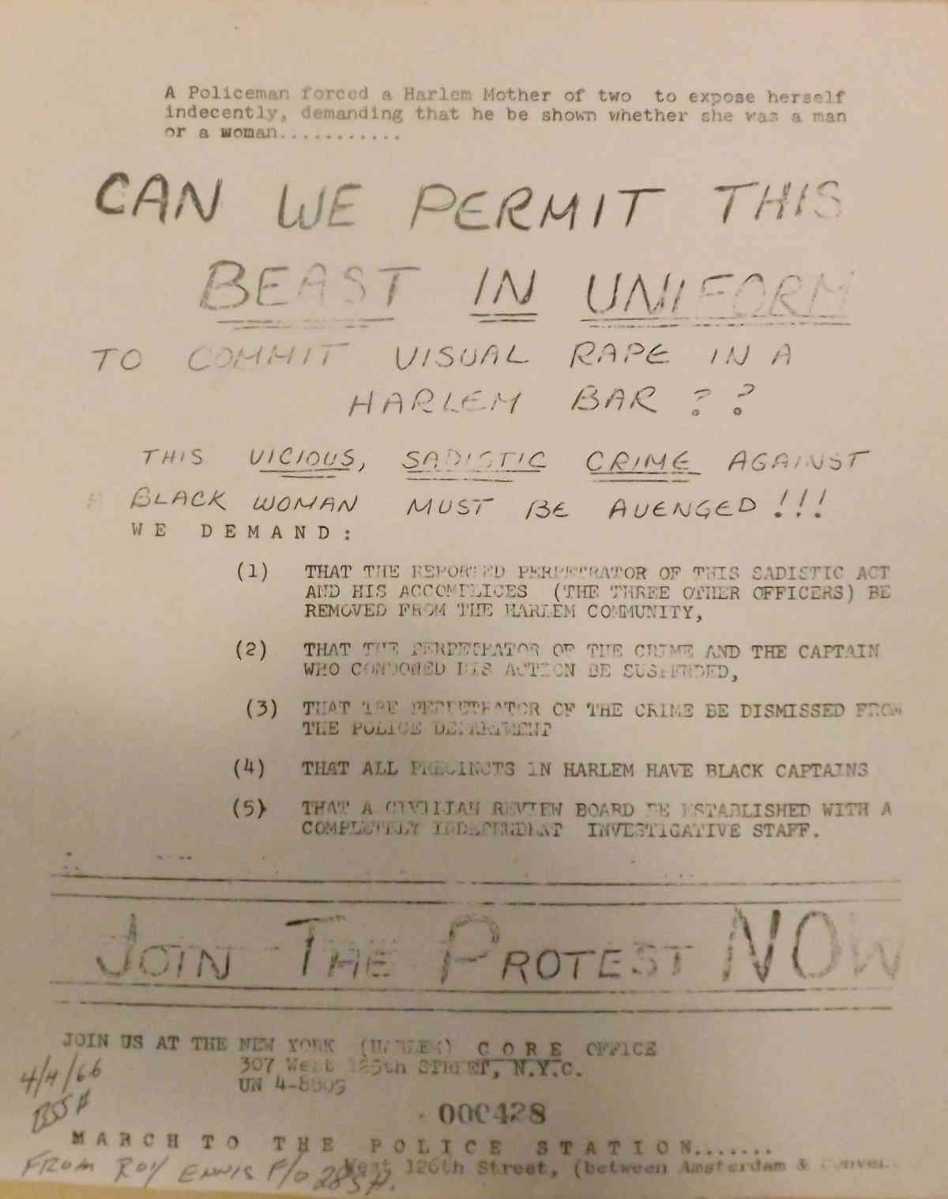

Uhl allegedly took 32-year-old Gertrude Williams, a married heterosexual with two children, into the kitchen and forced her to prove that she was female by partially undressing. When the group learned of Uhl’s conduct, it issued a press release calling for protests and demanding that Uhl and other officers involved be disciplined.

“For many years, CORE has pointed out that New York City has two kinds of law enforcement — one for the respectable white majority, and another for Negroes, Puerto Ricans, and for people that might be called non-conformist or bohemian,” the group said in a February 28 press release. “A deep smouldering [sic] resentment exists between the police and minority communities, caused in large measure by the actions of a small number of police officers.”

No record that Gay City News found has CORE again referring to “non-conformist or bohemian” people. The group mounted several protests. Ten people, including Roy Innis, who would go on to lead CORE, were arrested during the first demonstration when they blockaded the entrance to the 26th precinct on March 3. Protesters at that demonstration carried signs that used Uhl’s badge number and read “#21349 a pervert in uniform. He must go.” and “#21349 what will this pervert do next.”

On March 8, a group of CORE members marched through Harlem to the Salem Methodist Church at 129th Street and Seventh Avenue for a town hall meeting. Mayor John Lindsay was expected at that town hall, but he sent William Booth, the director of the city’s Commission on Human Rights in his place. A captain in the 26th precinct was transferred to another command following the incident.

The Williams incident fueled an ongoing push for a Civilian Complaint Review Board, according “The Ungovernable City: John Lindsay and His Struggle to Save New York,” a 2001 book by Vincent J. Cannato.

“It gave fodder not only to the campaign to install a Civilian Complaint Review Board, but also to militants like Roy Innis, head of Manhattan CORE, who called on blacks to ‘escalate the war’ on ‘vicious racist acts by police.’”