ILLUSTRATION BY MICHAEL SHIREY

A year ago, world attention on Russia focused on two things –– the impending Winter Olympics in Sochi and new legislation that, under the guise of preventing “homosexual propaganda” targeting children, in fact was the leading edge in a legal and extralegal assault on that nation’s LGBT community. Thanks to the efforts of activists worldwide, those two issues were often intertwined, with calls for boycotting the Games resulting in major world leaders, including President Barack Obama, choosing, in rather pointed fashion, to skip Sochi.

Russian vodka was dumped, US corporations were urged by some to divest, and the New York City and State comptrollers alerted companies in their investment portfolios who were Olympic sponsors or doing business in Russia to their concern about the anti-gay climate there. US advocacy and philanthropic groups organized efforts to provide financial support to Russian LGBT organizations.

Twelve months later, the world is once again focused on Russia, this time for its provocations for armed resistance to the government of Ukraine –– a crisis that in mid-July led to the downing of a civilian aircraft and nearly 300 deaths. The global outrage this time took on a considerably more muscular posture, with Obama and Western European leaders imposing significant economic sanctions, which now show signs of dissuading President Vladimir Putin from further escalation.

The questions hanging out there are: What has become of Russia’s embattled LGBT community? How do its members perceive the hurdles facing them? And, what, if anything, are they looking for in terms of international support?

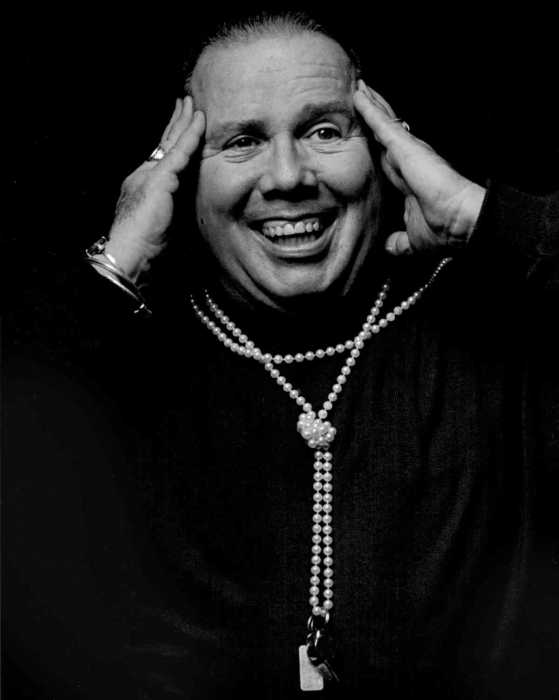

In a new documentary, Michael Lucas, a gay man who left Russia two decades ago at 23 and made his name in New York as a producer of gay porn films, explores those issues, with the assistance of co-director Scott Stern. “Campaign of Hate: Russia and Gay Propaganda” features conversations with more than a dozen gay men and lesbians, most of them activists in Moscow and St. Petersburg. It also includes an interview worthy of “Borat” –– only deadly serious –– in which Vitaly Milonov, a St. Petersburg official and a prime mover behind the legal attack on LGBT Russians, spews hate-filled rhetoric about sickness, Satan, and Sodom and Gomorrah apparently unaware he is on camera with a gay, Jewish ex-pat who makes adult films.

At a recent screening of “Campaign of Hate” at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah (CBST), Lucas made no secret of his disdain for his homeland and his deep pessimism about the prospects for improving the lot of LGBT Russians. His film, though, allows a variety of perspectives to be heard, and many reflect determination to dig in against the wave of homophobia sweeping Russia. Gulya Sultanova and Manny de Guerre, two of the three organizers of the Side by Side LGBT film festival held every fall in St. Petersburg, talked about how the 2013 event faced five bomb threats and numerous street protests, at least one of them spurred by the homophobic Milonov. Despite those dangers, the festival, drawing film luminaries including Gus Van Sant and Dustin Lance Black, was a potent symbol of defiance against the crackdown. Anton Krasovsky, a top news anchor until he came out on air during an early 2013 debate about the anti-gay law then under consideration, said he is now engaged in “my own battle, with no weapons and no barricades.” Filmmaker Elena Kostyuchenko told the story of a public kiss-in she organized that drew a violent response from street thugs. Intent on remaining visible, she acknowledged she can no longer ask others to accept the risks that sort of public demonstration entails.

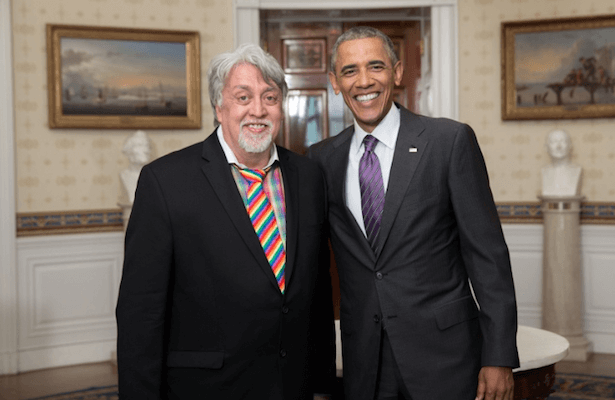

Filmmaker Michael Lucas with Masha Gessen (center), her spouse Darya Oreshkina, and their three children. BREAKING GLASS PICTURES

Masha Gessen, a journalist and for years the best known out LGBT Russian, was among several interviewees who argued the new law signaled to violent homophobic gangs open season on gays and lesbians. Some Russian officials don’t shy away from making that message explicit. Saying the new law did not go far enough, another top TV anchor, Dmitri Kiselev, who is the deputy general director of the Russian State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company, issued a stunning on-air anti-gay attack, saying, “Their hearts, in case of the automobile accident, should be buried in the ground or burned as unsuitable for the continuation of life.”

Gessen is unambiguous in her critique of what’s going on here, calling the wave of homophobia and violence “a concerted campaign from the Kremlin.” She tells Lucas, “It’s war rhetoric. The enemy is less than human… and scary. It’s very reminiscent of Nazi rhetoric.”

Yelena Goltsman, a Kiev-born New Yorker who leads RUSA LGBT, a group for Russian-speaking LGBT Americans that is in frequent dialogue with gay Russians, concurred, telling Gay City News that to focus on how many Russians have been snared by the new law misses the point. “That is not the aim,” she said. “The law makes it not normal to be gay and allows Russians to treat LGBT people as second-class citizens. And neo-Nazis get permission for their violence.”

It’s striking how many of Lucas’ interviewees offer personal stories of being gay-bashed. Some of the incidents are attacks an LGBT New Yorker or Parisian might suffer, but the frequency of experiencing violence appears clearly higher among the Russians. In the year since the new law took effect, anti-gay militants have flooded the Internet with horrific videos of gay men facing torture after being lured into danger under false pretenses. Even more draconian legal curbs on LGBT life could be in the offing.

For the past year and a half, proposals to take children away from gay and lesbian parents have been discussed, though not yet formally advanced. St. Petersburg’s Milonov singled out Gessen and her “perverted” family in arguing the need for such a measure. Late last year, Gessen, who had repeatedly called for resisting Putin’s war on gays on all fronts, and her spouse, Darya Oreshkina, were sufficiently concerned about the possibility of such legislation that they left Moscow, taking their children to live in New York.

Lucas’ film presents a consensus view that while Russia has never been an LGBT paradise, the situation has worsened in the past several years. Journalist Krasovsky, asked what it felt like to be gay there, answered, “Humiliating,” and Alexander Kargaltsev, a filmmaker who left Russia in 2010, said that “feeling shame… is so normal we don’t even think about it.” But Krasovsky hastened to add that the climate for LGBT Russians was better even in the immediate post-Soviet ‘90s than it is today.

Contacted by Gay City News, Valery Sozaev, a Saint Petersburg activist who has worked with Coming Out and the Russian LGBT Network, said as recently as 2008 there were very few LGBT organizations to find elsewhere in the country but that “in six years, the situation has changed. It has changed so much that it’s difficult for me to imagine a discussion of Russian-language media without mentioning LGBT issues.”

Gessen told MSNBC that in 20 years of living in Russia she spent a decade feeling like the only out person there, but that in recent years, LGBT organizations, cultural initiatives, and bars had sprung up widely. “It was not moving backwards,” she said of the period prior to 2013.

The new repression, Lucas and his interviewees agree, is scapegoating, pure and simple, aimed at shoring up Putin’s political position. “Putin sees his constituency shrinking,” Gessen said. “He needs to show there is an enemy. Nobody represents the other better than gay men and lesbians. Most people believe they’ve never met gays and lesbians.” That last point was vividly underscored by a number of person-on-the-street interviews in Lucas’ film.

Sozaev and Roman Kalinin, a Muscovite who describes himself as Russia’s first gay activist, agreed about Putin’s motivation, but see the anti-gay crackdown as part of a broader assault on human rights there. “It’s clear that Russian society today is living in a period of severe repression,” Sozaev wrote. “It’s clear that any person in our country who learns self-respect will then find themselves under constant pressure; they will be denied their rights and freedoms, and be humiliated for having that very self-respect… And I’m not just talking about LGBT, I’m talking about everyone.”

“Any dictatorship needs an enemy,” Kalinin told Gay City News. “A year ago, it was gay. Now Ukrainians. No ideology, just business.” Kalinin and LGBT RUSA’s Goltsman suggested the Russian media’s current obsession with the Ukraine crisis has cooled its attacks on gays.

Many activists, in the film and otherwise, welcome international support for LGBT Russians, though even the most vocal proponents of a global effort acknowledge disagreements over tactics within Russia. Asked last year about dumping Russian vodka and boycotting the Games, Gessen said, “I support all these efforts.” Putin, she argued, “thought nobody was watching.” The global outcry, she said, was “a big surprise to them. It’s not going to make them reconsider those laws, but it may perhaps get them to dial back the campaign of hate.”

In contrast, journalist Krasovsky told CNN, “Russian gay people need international support, but international support is not a boycott of Sochi Olympic Games… If you want to boycott Olympic Games in Russia, you’re trying to boycott seven million gay people in Russia. You want to boycott me.”

One point on which there is agreement is the imperative that European and North American activists take their lead from those on the ground in Russia. Foreign support must be “align[ed] with the mode of thinking and the approach that are employed locally,” Anastasia Smirnova, who coordinated a coalition of Russian LGBT activists working with the US-based Arcus Foundation’s Russia Freedom Fund on ways to put American dollars to work in support of gay groups there. Smirnova told Gay City News that the Fund has funneled about $300,000 to nine different groups across Russia doing work on a variety of legal and community building issues as well as on specific public events.

Earlier this year, Smirnova and a colleague, Polina Andrianova, faced questioning from San Francisco blogger Michael Petrelis about how the Arcus funds steered clear of requirements in Russia’s strict foreign agents law. The women replied that the funded activities do not qualify as “political” and so do not fall under the law, but Smirnova declined to elaborate, saying, “How exactly it is possible to mitigate risks while being transparent is not a subject of an open discussion –– as no one here would like to make life difficult for any Russian organization.”

Arcus did not respond to Gay City News’ request for comment on the Russia Freedom Fund, so, beyond Smirnova’s characterization, the precise way it is assisting the LGBT community there is not clear.

At CBST, Lucas, who last year participated in a variety of protests in New York aimed at Russia, said he now believes things will not improve “until Putin is gone, which means when he is dead.” Activist support from outside Russia simply hands him “the proof that it is coming from the West,” he said, further fueling the new anti-gay law’s popularity. The only thing Americans can do to support LGBT Russians, Lucas argued, is to help them leave.

RUSA LGBT’s Goltsman acknowledged that her group hears from many in Russia who now think it may be time to emigrate. But like Gessen, she believes that without international outcry, Putin can carry on his crackdown with impunity. In any event, emigration would scarcely be a viable option for any but a small fraction of LGBT Russians.

Sozaev, the St. Petersburg activist, acknowledged, “I do see people packing their bags and leaving and not just LGBT.”

But he is not among them.

“I’m really sad when LGBT activists make the decision to leave,” he wrote. “But I don’t judge them. I know that it only means that I will have to work harder and harder to do the work of the activist who left. There won’t be time to relax. But the problem of lack of manpower is nothing new. It was that way before. And new activists turned up. They’re turning up now.”