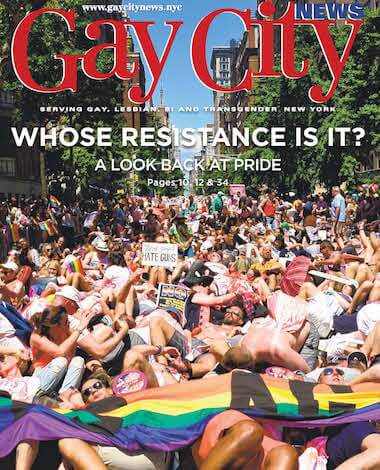

COVER PHOTO BY DONNA ACETO

BY PAUL SCHINDLER | The issue was emotionally fraught — with charges of anti-Semitism and of genocide traded back and forth. But the Center’s solution at the time was one I criticized — placing an indefinite moratorium on any discussion of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in its space. What should stand as a model refuge for open discussion across New York’s large and diverse LGBTQ community instead became someplace where important issues of the day were explicitly sidelined. That’s not what the Center should be about.alf a dozen years ago, a divisive battle broke out at New York’s LGBT Community Center between supporters of Israel and activists opposed to the Jewish State’s treatment of its Palestinian and Arab residents. Some LGBTQ New Yorkers, including several elected officials as well as others with influence on the Center’s board, objected to the use of Center space by Queers Against Israeli Apartheid and other critics of that nation.

Fortunately that policy was shelved when it reached its absurd apotheosis — the Center’s refusal in early 2013 to allow lesbian writer Sarah Schulman, a Jewish critic of Israel, to discuss her book “Israel/ Palestine and the Queer International.”

This Pride season, we’ve sadly learned that it’s not necessarily supporters of Israel who are the first to try to straightjacket the LGBTQ community’s discussion of the Middle East. Shocking news out of Chicago reported that several women carrying Rainbow Flags bearing Stars of David were told to leave the Dyke March there. According to the Windy City Times, an LGBTQ newspaper, members of the Dyke March Collective who intervened to eject the women told them the event was “anti-Zionist” and “pro-Palestinian” and that the Star of David “triggered” other dykes marching.

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Some of the ensuing debate centered on whether or not the Star of David is an explicitly Zionist symbol, but taking first things first: What kind of historical blindness and moral obtuseness would lead so-called progressives to ban the Star of David? Did these collective members have no awareness of how the Nazis used this symbol as a way to ostracize and, over time, exterminate Europe’s Jewish population? Did they have no appreciation for how excluding these women from the Dyke March would inevitably be seen as anti-Semitic?

Beyond that tone-deafness is the broader question of whether community space — whether at New York’s LGBT Community Center or in Chicago’s Dyke March — should be restricted based on one’s view of the Israeli-Palestinian question. I understand that critical human rights questions and values are at stake in the Middle East, and I would never argue that our community has no stake in how such issues are adjudicated. But we make a grave mistake in demarcating “citizenship” in our community based on the views someone has on this very difficult matter.

Debating questions like this should be embraced as a welcome sign our community can tolerate and contain disagreement — even ones where deeply held beliefs are involved. Arguing that certain ideas are dangerous because they “trigger” others is an intellectually and morally lazy assertion that we’re better off if we avoid certain difficult issues by simply not talking about them.

We’re better and stronger than that — or we ought to be.

Our community faces enormous existential threats under the new Trump administration, and we better get serious about ordering our priorities. Otherwise we run the risk of drowning in our own divisions, unable to put up any kind of consistent and concerted resistance.

Activist groups — Rise and Resist and Gays Against Guns, chief among them — laudably stepped up this year and won a big concession from Heritage of Pride (HOP), which produces the LGBTQ Pride March: prominent placement in the order of march for critics of the Trump regime. Other activists, less willing to do the spadework, instead chose to piggyback off the resistance contingent’s efforts, jumping in with the goal of blockading the March based on diffuse demands that police officers and corporate sponsors not be allowed to participate. Absent from any of the HOP forums where other activists made their case, Hoods4Justice simply threw some rhetoric up on social media and then showed up. Tellingly, when a dozen of them managed to tie the parade up for half an hour outside the Stonewall Inn — blocking several LGBTQ law enforcement contingents from moving forward — they made no particular effort to educate the confused spectators about their demands.

Instead, they focused on ugly provocations. One marcher wore a sign reading, “Good queers kill cops” on her back. A disruptor filming those sitting-in for online PR purposes could barely stay focused on that task as he screamed “pig” and “Nazi” to a police officer calmly trying to bring the blockade to an end.

The community would do well to open up debate over the character of the Pride March. Hoods4Justice members are hardly alone in their discomfort with the commercialism on display. Nor are they the only activists concerned about continued police abuses aimed at segments of the LGBTQ community.

But where were these disruptors prior to June 25? And what gives them the right to read out of the community LGBTQ law enforcement professionals who, against very long odds, have brought a queer perspective into policing in this city and elsewhere?

Principled and strategic resistance is what is needed now. Angry and divisive tantrums that provide succor for nihilistic narcissism, however, get us nowhere.

Again, we ought to be stronger and better than that.