A shipwreck off the coast of Turtle Island. In the background, European would-be settlers cling for dear life to their upturned vessel. A shark’s dorsal fin cuts the surface of the stormy sea. In the foreground, drenched settlers claw at a rocky promontory, pleading with outstretched arms for the Indigenous people on land to drag them ashore.

But, irony of ironies, the Indigenous cannot act because they are frozen in the poses the canon of art history has straightjacketed them into: the Noble Savage, the Heroic Warrior, the Supine Maiden with body as fertile and welcoming as the land she lies on.

The figure who can and does step to the fore — wearing a pair of Louboutin heels no less — is gender-fluid Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. She is her own creation. Taut, nude body bent forward at the waist, rainbow-colored earring dangling, she grasps the hand of a lone African man whom the settlers were bringing by force to work this land they will rename North America. Only fair: the African’s wrists are manacled, his chances for survival halved. At the African’s back is a brown Asian man. Were this a moving picture, the next frame might show him, too, getting saved.

As she acts, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle locks eyes with you, the viewer. What sense, her eyes ask, do you make of this version of conquest, one you’ve never seen represented in art?

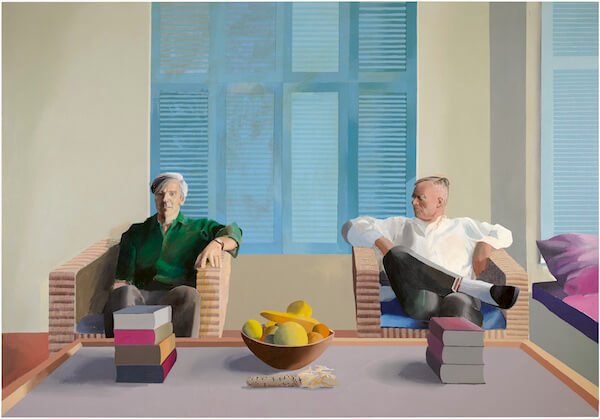

This is a description of the painting, “Welcoming the Newcomers,” by visual and performance artist Kent Monkman. Eleven by 22 feet in dimension, the canvas is one of a pair of identically sized paintings, together titled “mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People),” installed in the Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, from December 17 to April 2020. The painting’s twin, “Resurgence of the People,” incorporates contemporary images and themes into a reenactment of the scene in “Washington Crossing the Delaware” (1851) by the German-American artist Emanuel Leutze. Replacing Washington, who is shown leading a boatload of revolutionary fighters, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, striking a similar pose, stands amongst equals who are mostly Indigenous women and children. The painting challenges the Eurocentric, androcentric, heteronormative depiction of autocratic leadership that is a mainstay of history painting, a stark contrast to the communitarian, matriarchal structure of many aboriginal societies.

“Resurgence” also echoes “Liberty Leading the People” (1830), by master painter Eugène Delacroix (in the collection of the Louvre Museum, in Paris), which depicts Marianne, mythic embodiment of the French nation, holding aloft the tricolor flag. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, representing Indigenous nationhood, holds aloft the feather of a large bird, a sacred symbol in Indigenous spirituality.

Monkman, 54, is a member of the Cree Nation. Born in the Canadian province of Manitoba and now based in Toronto, Monkman addresses issues of displacement and reclamation in his art, centering the experiences of the First Nations, the indigenous peoples of Canada. Monkman inserts his own body and personhood into his work. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle is a Two-Spirit (an Indigenous identity of plural gender and sexuality) alter ego he created through which to make claims about art and history as a queer Native man. Monkman does not only render himself as Miss Chief Eagle Testickle on the canvas, he gives performances as Testickle dressed in an elaborate gown the shape of a teepee, fanciful feathered headdress, and stiletto heels.

“I wanted an artistic persona that could travel through time to reverse the gaze and look back at European settlers,” he said.

The artist gave one such performance to a packed audience at the Met on December 19. In it, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle delivered a 20-minute monologue, read theatrically from a make-believe book of origins, that recounted the arrival on Earth from the heavens of a Two-Spirit creator of the First Nations, followed by the brutal arrival of the colonizers.

Following the performance was a public conversation between Monkman as himself and Met curator Randall Griffey, who helmed the “mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People)” project. This installation is the first commission in a new program at the museum that invites artists to create and display original works inspired by its permanent collection. In addition to the works by Leutze and Delacroix, influences on Monkman’s paintings can be seen in the work of a pool of artists from diverse periods and artistic traditions.

“The two paintings together really speak about the arrivals and migrations and displacements of people around the world,” Monkman said. “The Great Hall is this place of people entering and people leaving. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle is literally bending over to assist people arriving to North America. That has to do with generosity.”

MISTIKÔSIWAK (WOODEN BOAT PEOPLE) | Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Ave. at E. 82nd St. | Through Apr. 9: Sun.-Thu., 10 a.m.-5:30 p.m.; Fri.-Sat., 10 a.m.-9 p.m. | $25; $17 for seniors; $12 for students; free for those under 12 | metmuseum.org