BY SUSIE DAY | This past year was good for prison activists. Those who advocated for high-profile political prisoners in the federal system celebrated when President Barack Obama commuted the sentences of Chelsea Manning and Oscar Lopez, both now scheduled for release on May 17. Activists who supported less-known “social” prisoners, most serving inordinate time for what the media like to call “nonviolent drug offenses,” rejoiced at Obama’s unprecedented 1,715 commutations by the end of his presidency.

Locally, New York State activists, having spent years beseeching Andrew Cuomo to grant prisoners clemency, finally saw a little light when Cuomo commuted the 75-year-to-life sentence of Judith Clark, as well as those of six other people with felony convictions. All told, about 1,722 actual human beings, who once contemplated their deaths inside prison, are now free or facing the increasing prospect of walking out alive.

But given that Obama also denied a record number of petitions (14,485, including Leonard Peltier’s) and that this country has for years held the world’s largest prison population, there remain about 2.2 million people behind US bars. Social prisoners and political prisoners, disproportionately black and brown. People like my friend Herman Bell.

SNIDE LINES

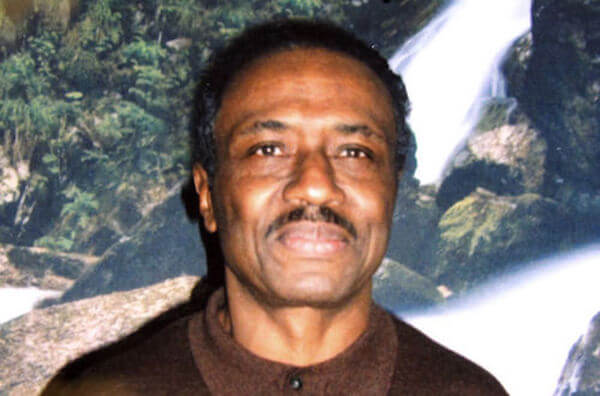

Eleven years ago, I wrote about visiting Herman, a former Black Panther convicted of killing two police officers and sentenced to 25 years to life. In 2006, my partner Laura, our Canadian friend Tynan, his two-year-old daughter Frankie, and I visited Herman at the Eastern Correctional Facility on his 58th birthday. Herman was then preparing to go before the New York Parole Board for the second time.

I’m writing again about visiting Herman, except that Frankie is 13 and prefers to be called Franca; and Herman has just turned 69 and has now been denied parole seven times.

Herman’s also been moved around to several other prisons, so these days, we take a five-hour bus ride to see him at the Great Meadow prison in Comstock. Since this “correctional facility” allows prisoners only three visitors, Franca couldn’t come this time. Ty, Laura, and I go through the usual body scan and metal detection before we’re allowed in the visiting room. We’re assigned a bench behind a long metal table set on painted cinder blocks, over which Herman will lean to hug us when he gets here.

“Imprisonment exacts an incalculable toll on the body and mind,” Herman once wrote. It’s “the closest descent into Hell as one can imagine.” He ought to know. Herman’s been caged since he was 25. Research shows that, because of stress, bad food, and inadequate medical care, people in prison age rapidly – so fast that by the time they’re 50, they’re considered “elderly.” That’s one reason why Laura, with Herman’s encouragement, helped start an organization called Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP).

Now in walks Herman, in a rumpled green uniform, much the same “tall, sweet-smiling, quiet man” I described over a decade ago. But he’s looking more worn and tired. For weeks now, he’s been telling us how he expects to lose his cell on the honor block. There are rumors that, because of the 2015 escape of two honor-block prisoners at Clinton prison, honor blocks in every New York state prison may close.

If you’re a long-term prisoner in New York, honor blocks are an essential means of survival, especially as you age. To be granted the “earned housing” privilege, you have to work long and hard, avoiding any write-ups for misbehavior. The Comstock honor block isn’t much different from the rest of the prison, except that it’s blessedly quieter and has its own recreation area, making it easier to get to the phones to call the people allowed on your list. Without it, there’s uncontrollable noise, a kind of psychic drowning.

Herman appraises the spread of junk food we’ve amassed from the vending machines. He starts to peel the plastic off a microwaved burrito, and we catch up on life. Laura keeps Herman posted on RAPP meetings. Tynan mentions Franca’s roller derby team, the Rhythm and Bruise. Herman’s relieved he didn’t see his name on this morning’s list of people to be moved off the honor block. He figures he’s safe for now.

I buy a chocolate chip muffin, hoping it will pass for a birthday cake; but first, some prison gossip. Rural, intensely Caucasian Comstock – yet another prison holding mostly African Americans and Latinos – seems to have employed exactly one black guard, who, Herman says, refers to himself as French Canadian. “Name of Deshawn,” sneers Herman, “yeah, right.” The muffin is still sitting unopened when a white guard taps Herman on the shoulder.

“We’re packing up your cell,” he says. Herman can stay at the visit or go back to see that his possessions – which fit into a few cardboard boxes – aren’t broken or waylaid on their way to another cellblock. Herman says he’ll stay with us, but we insist that he go protect his stuff.

People who’ve never been inside a prison usually can’t fathom how small, bureaucratic changes like this can prove life-threatening. And disappearing honor blocks may not be all that’s coming down the pipeline. Governor Cuomo, citing budgetary constraints, has proposed cutting visiting days at maximum-security prisons to three a week. Then there’s Cuomo’s 2017 State of the State platform. Even after Judith Clark’s commuted sentence, it doesn’t mention releasing other prisoners in the “graying” population. Instead, Cuomo plans to “create a 50-bed dormitory at Ulster Correctional Facility to house eligible individuals aged 55 years or older.”

As the Trump regime sinks its talons deeper into our body politic, people like Herman – anybody left behind bars – will be the first to be forgotten. Standing Rock, refugees, healthcare: such emergencies will – rightfully – demand our attention. Yet part of the trick of our survival will be to connect our lives to the lives of these people inside, grappling with their own deepening hells.

Here at Comstock, Herman returns to our visit. He’s shaken, but cracks that his new cellblock resembles “south of the Mason-Dixon line.” Which makes us worry at yet another level. We sing “Happy Birthday,” share Herman’s cupcake, shoot a crap game with “dice” Ty has improvised from scrap paper, and leave when visiting hours end.

We’ll need to contact Herman’s wife. Tell her he may not be able to call for a while.

Susie Day is the author of “Snidelines: Talking Trash to Power,” published by Abingdon Square Publishing.