Isaac Julien’s implausible narrative explores image creation in a diverse society

Isaac Julien’s “Baltimore,” currently on view in Chelsea, ambulates a large and varied cultural terrain. It charts the course of two characters who, during the course of a day, navigate separately an implausible route through urban streets, an art museum, a library, and a wax museum. Imagine a Blaxpoitation version of “Bladerunner” set at the New York Public Library or the Metropolitan Museum of Art and you get the feel of the piece, which is in parts raw, artful, ghetto, retro, and sci-fi.

The first character is a cigar-smoking, fedora-sporting, unflappably cool cat, played by veteran Blaxpoitation actor and director Melvin Van Peebles. While visiting the European painting galleries of the Walters Art Museum, he stoically comes upon a wax facsimile of himself, identical in every detail except the color of its hat. Standing just behind it are wax figures of Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., each gazing somberly over one shoulder. Behind them is a collection of other Great Blacks in Wax arranged in the gallery whose walls are covered in old master paintings.

In yet another example of discombobulated space, the whole scene is set up and lit for a photography shoot, the product of which is some of the photographs hanging in the front room of Metro Pictures.

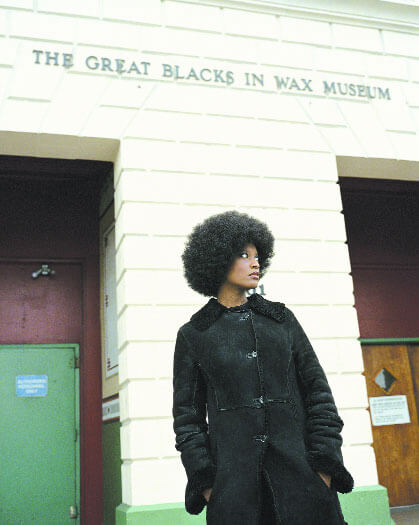

The second character, Angela, is a Pam Grier type: retro, reserved, stylish. After watching a simulated space launch at the Great Blacks in Wax Museum, she sheds her afro, produces and cocks a silver pistol, and magically transforms into a bad ass, black, bald, futuristic heroine. At one point she kick–leaps like Keanu Reeves in “The Matrix” into the lofty heights of the central chamber of the Peabody Museum. Upon landing with a sharp confident clack, she turns slightly back toward the camera with a self-aware smile. Angela’s performance is a delightful paean to the empowering potential of art.

These sorts of disrupted expectations, upset sequences, illogical turns, and hyper leaps characterize the narrative. By juxtaposing and in some cases conjoining different perspectives and spacial arrangements, everything from Renaissance painting to blaxpoitation cinema, Julien frames a vital inquiry into how perspective—the way things are presented—affects identity.

Further, he illuminates how representation often, if not always, privileges one perspective over others. These are some of the most compelling issues at the heart of contemporary cultural production; they get to the heart of what it means to create images in a complex heterogeneous society.

A trip to “Baltimore” is a funky sojourn into the cultural landscape. In a feat not unlike one of Angela’s, Julien uncannily sketches enormous ambitions into a work that remains breezy, jive talking, visually entertaining, cinematically adept, and intellectually engaging. Although his hook doesn’t dig too deeply into the issues at hand, there’s time yet to land that whale.